New Mars Rover Could Far Outlive Its Lifespan

When NASA's newest Mars rover, Curiosity, lands on the Red Planet in a little over two weeks, it will begin an ambitious mission that is expected to last approximately two Earth years. But with no shortage of intriguing mysteries to tackle, how long could the car-size rover actually last on Mars?

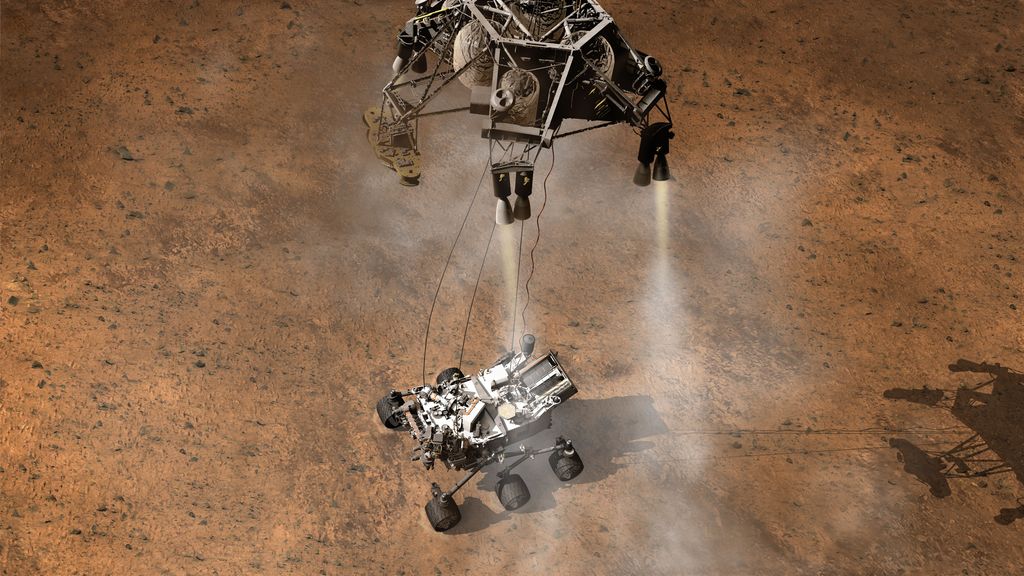

After almost eight months of traveling through space, NASA's Curiosity rover, or Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), will attempt to land on the Red Planet on the night of Aug. 5. The 1-ton rover will set its wheels down at Gale Crater, a 96-mile-wide (154-kilometer) scar on the Martian surface from an ancient asteroid impact.

As Curiosity explores Gale Crater and a mysterious mountain, called Mount Sharp, at its center, the rover will search for clues that the planet is, or ever was, capable of harboring past or present microbial life.

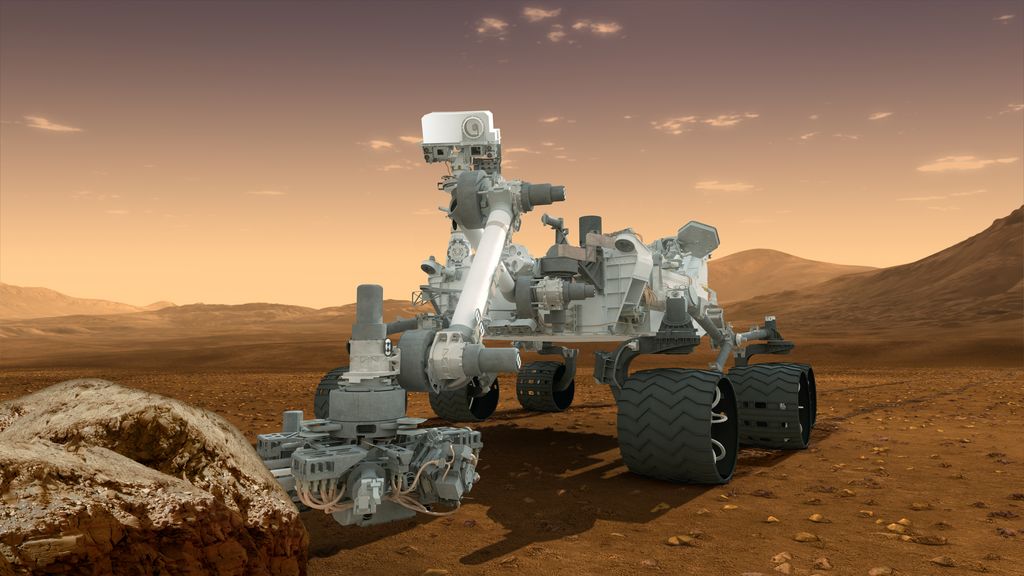

Curiosity is the most complex robotic explorer that has ever been sent to Mars, NASA officials have said. The rover is equipped with a suite of 10 instruments that will allow scientists to study the rocks, soil and atmosphere of Mars.

The $2.5 billion mission is expected to be carried out over two Earth years, but it is conceivable that the Curiosity rover's life on Mars could be extended if necessary, said Pete Theisinger, MSL project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. [Photos: How Curiosity's Nail-Biting Landing Works]

Powered by plutonium

The Curiosity rover is carrying a nuclear power source to charge its batteries and fuel its onboard systems throughout its planned two-year mission on Mars. The system uses heat from the decay of plutonium-238 to generate 110 watts of electrical power to charge the rover's batteries.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For 50 years, NASA has used these types of nuclear systems, called radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), to power unmanned probes to study planets and other objects in the outer solar system.

In the case of the Mars Science Laboratory, an RTG was necessary because solar panels alone could not generate enough power to run the huge rover, NASA officials said.

Since RTG-powered rovers do not require sunlight to operate, these spacecraft are capable of exploring more diverse locations, without as much concern about the season, time of day or latitude. Solar-powered rovers must land and operate within a fairly narrow latitude band near the equator, where adequate sunlight can be accessed to generate electricity, agency officials explained.

So does that mean Curiosity should last longer on the Martian surface? Not necessarily, Theisinger said.

While the rover could realistically survive five or six years on Mars, there are three main areas that could limit Curiosity's life: the rover's onboard mechanisms, its batteries, and its nuclear-powered RTG, he explained.

"We test the mechanisms usually for three times life — sometimes two — and we don't test them to failure," Theisinger told SPACE.com. "So, all the mechanisms have been tested to last two to three times longer than we expect the mission to operate, if they haven't failed in that period of time."

The rover's batteries and RTG are designed to operate on Mars for at least 687 Earth days, but could endure for longer. [Infographic: History of Robotic Red Planet Missions]

"The RTG suffers from the degradation of plutonium dioxide, but that lasts a long time," Theisinger said. "I think from the RTG, I would expect to get 10, 12 or 15 years out of it."

As such, Curiosity's greatest vulnerabilities are likely the parts that control its ability to move around on the planet's surface.

"The point you would say at which we first run out of the warranty would be with the mechanisms controlling the driving and those kinds of things," Theisinger said. "There's some redundancy there, though. Each of the wheels has its own drive motor, so there's a motor inside the hub for each of the driving wheels, and there are steering wheels on the four corners. If we lose a drive motor on the wheel, we can still drive with five. So, there's some redundancy with what we have."

In the footsteps of past rovers

Curiosity's predecessors, the twin Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, surprised scientists by far outlasting their warranties on the Red Planet.

Spirit and Opportunity touched down on Mars about three weeks apart in January 2004. The solar-powered rovers were designed for three-month missions on the Martian surface, but the intrepid robot explorers lasted far longer than was originally expected.

Spirit was officially declared dead in May 2011, after getting trapped in unforgiving Martian sand. Opportunity, on the other hand, continues its trek on Mars, having already logged 21.4 miles (34.4 km).

But, since Spirit and Opportunity are solar-powered rovers, and Curiosity is powered with an RTG, it is difficult to compare the missions, Theisinger said.

"The reasons Spirit and Opportunity lasted longer are different, so you can't run away with that idea," he said. "Do I think Curiosity could last longer? It certainly could. Could it last 10 years? I don't think so. But could it last five years? You bet. If it lasted five or six years, I wouldn't be shocked. But you never know."

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.