Best Time to See Moon Craters This Month Is Now

As the moon makes its monthly trip around the Earth, the sun hits it from a variety of angles, but its many craters are rarely more amazing than they are this week.

At new moon, the far side of the moon is in full sunlight and the side which faces Earth is lit only by sunlight reflected from the Earth. Two weeks later, during the monthly full moon, the side facing Earth is in full sunlight and the far side gets no light at all from the depths of space.

The most interesting times to observe the moon are close to first and third quarter, when the sun casts glancing rays across the moon's surface, bringing its surface features into high relief. Over the next few evenings the sun will be rising on some of the most interesting craters on the moon.

The most characteristic feature of the lunar surface is the hundreds of craters which cover it. These are the result of bombardment by asteroids in the moon's early history. It surprises most people to learn that most of the moon's craters were formed over three billion years ago, long before life emerged on Earth. The face of the moon really hasn't changed much since then. [The Moon's Phases Explained (Infographic)]

Craters of the moon

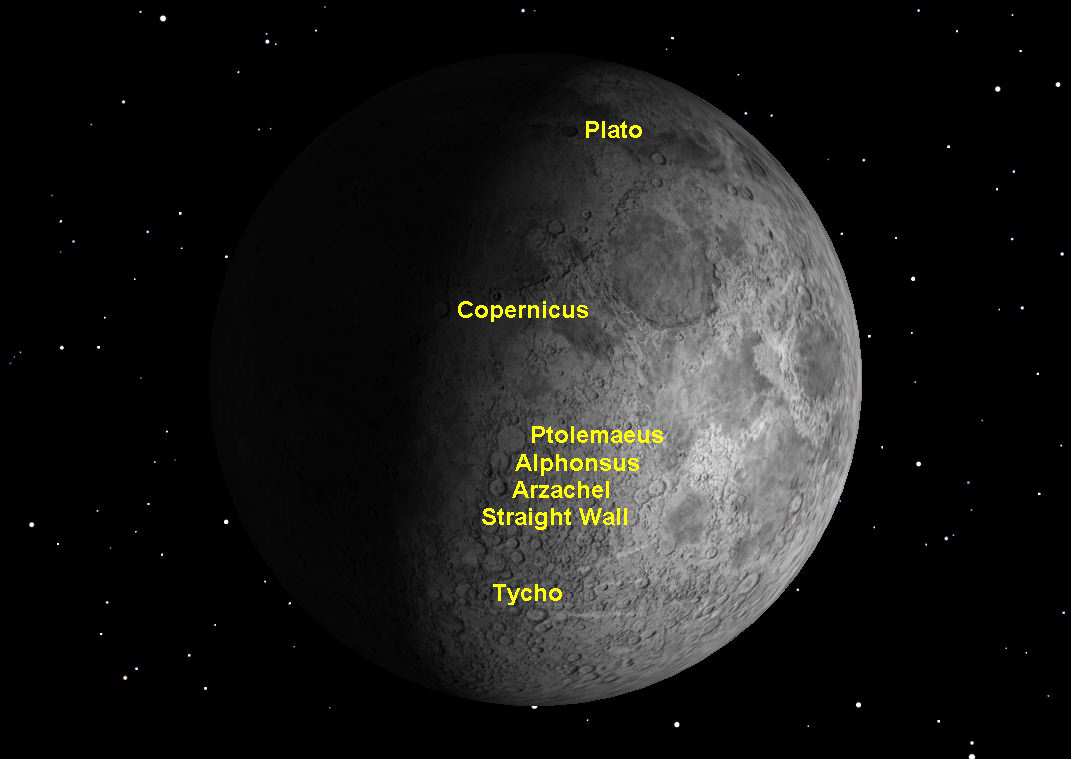

The first craters you will probably notice if you look at the moon over the next few nights are three large craters right in the middle of the sunrise line, called the "terminator." These are named from north to south Ptolemaeus, Alphonsus, and Arzachel.

Ptolemaeus, the largest of the three, is named for the famous Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, who lived and worked in Alexandria during the second century AD. It is a huge walled plain 95 miles (153 km.) in diameter. Its flat floor appears to be the result of a lava flow in the aftermath of an asteroid impact.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Alphonsus is a more typical crater with a central peak and terraced walls. It is named after King Alphonso the Wise of Spain who in the 13th century sponsored the compilation of the Alphonsine Tables which allowed calculation of the positions of the sun, moon, and planets. Alphonsus is 74 miles (119 km.) in diameter.

The third member of this trio is the smallest of the three, Arzachel, 60 miles (96 km.) in diameter. It is named for 11th century Arab astronomer Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Zarqali.

The moon's Straight Wall

While observing these three craters, look a bit to the south of Arzachel for a striking feature, the Straight Wall or Rupes Recta. This is a cliff or fault 68 miles (110 km.) long. Lit by the rising sun, it looks very high, but in fact is less than 1000 feet (300 meters) high.

About half way between the Straight Wall and the moon's south pole is Tycho crater, named for Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, the last great astronomer before the invention of the telescope. His accurate observations made in the late 16th century were accurate enough to allow Johannes Kepler to develop his laws of planetary motion.

Although not the largest crater on the moon, Tycho is one of the brightest, indicating that it is one of the youngest of the craters. It is the point of origin of a huge system of rays which encircle the moon, best seen in about a week when the moon is full. Tycho is 53 miles (86 km) in diameter with classic central peak and terraced walls.

Close to the moon's north pole is another crater with a smooth floor like Ptolemaeus: Plato, named for the famed Greek philosopher. It is smaller than Ptolemaeus, 68 miles (109 km) in diameter.

Because of its proximity to the moon's north pole and the moon's spherical shape, Plato looks like an oval but is truly circular when seen from above, in orbit around the moon. Experienced lunar observers use the visibility of several tiny craterlets on the floor of Plato as a test for their telescope's acuity.

Over the next few days, the moon will move in its orbit around the Earth so that the sun appears to rise over craters further west. Most prominent of these is Copernicus, 58 miles (93 km) in diameter. Nicholas Copernicus was the 15th century Polish astronomer responsible for moving the center of the solar system from the Earth to the sun.

Learning to identify the craters of the moon serves to familiarize you with the geography of another world, as well as the history of the science of astronomy. It is also a reminder of the international nature of astronomy, with craters named for scientists of many different nations.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing photo the moon or its craters that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send images and comments to managing editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.