Hubble Searches for Oxygen on the Moon

This summer, scientists pointed the Hubble Space Telescope at the Moon to take a closer look at its soil.

The results were announced today.

"Our initial findings support the potential existence of some unique varieties of oxygen -rich glassy soils in both the Aristarchus and Apollo 17 regions. They could be well-suited for visits by robots and human explorers to learn how to live off the land on the Moon," said NASA's Jim Garvin, lead scientist on the project.

While Hubble wasn't specifically designed to look at the Moon - it only has the resolution of a football field for an object so close - scientists can use the ultraviolet capability of its Advanced Camera for Surveys to analyze the contents of lunar soil, particularly minerals and ore that might contain oxygen.

Since the Moon does not have a breathable atmosphere, and spacecrafts have limited load capacities, harvesting oxygen from the soil may be critical for long-term human missions. Hubble found that the soil in the regions examined contained abundant amounts of ilmenite, a mixture of titanium, iron, and oxygen.

Laboratory experiments on Earth have shown that applying certain chemical processes to terrestrial ilmenite can easily liberate oxygen and water. Water can then be turned into oxygen and hydrogen, which could also be used for rocket fuel.

"The idea is to utilize resources there to reduce the costs of going to the Moon," project member Mark Robinson of Northwestern University said during the a NASA briefing today.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Other studies have found evidence for water ice near the lunar poles. While those areas might serve well for human outposts, they are not necessarily the first choices for science missions.

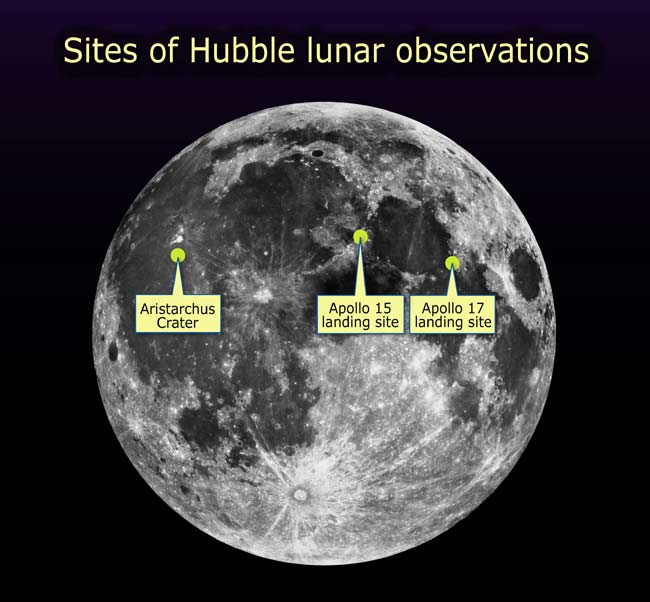

The Hubble team examined three lunar sites, two of which - the Apollo 15 and 17 landing sites - where soil chemistry is well known. The third was the Aristarchus crater, a "geologic wonderland" that has piqued geologists' interest for decades.

The Aristarchus crater is the brightest feature of the Moon's near side, nearly twice as bright as most spots on the Moon and visible to the naked eye. It's just 25 miles across but more than two miles deep. At only 450 million years old, it is one of the younger major features on the Moon.

More importantly, it sits in a region of the Moon that scientists believe was once rocked by volcanic explosions and tectonic shifts. The two-mile gouge exposes the historical record of what went on in the region, including the history of crust and mantle formation on a young satellite.

"Right in the midst of [this region] is this whopping big, very young crater that cut through the whole section," Garvin said. "And in geology we like cross sections."

Aristarchus crater was the planned landing site for Apollo 18, but no human or robot has ever set foot there, making it a likely target for the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter as it explores the lunar surface in 2008, according to current plans. Data from that mission, combined with Hubble's observations, will help plan the location of future robotic and human missions.

"This is a jumpstart for lunar exploration and science in the context of what we know," Garvin said.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.