Twin NASA Satellites to Probe Earth's Harsh Radiation Belts

A pair of spacecraft in suits of armor will brave one of the toughest environments in space when they launch later this month to study radiation around Earth.

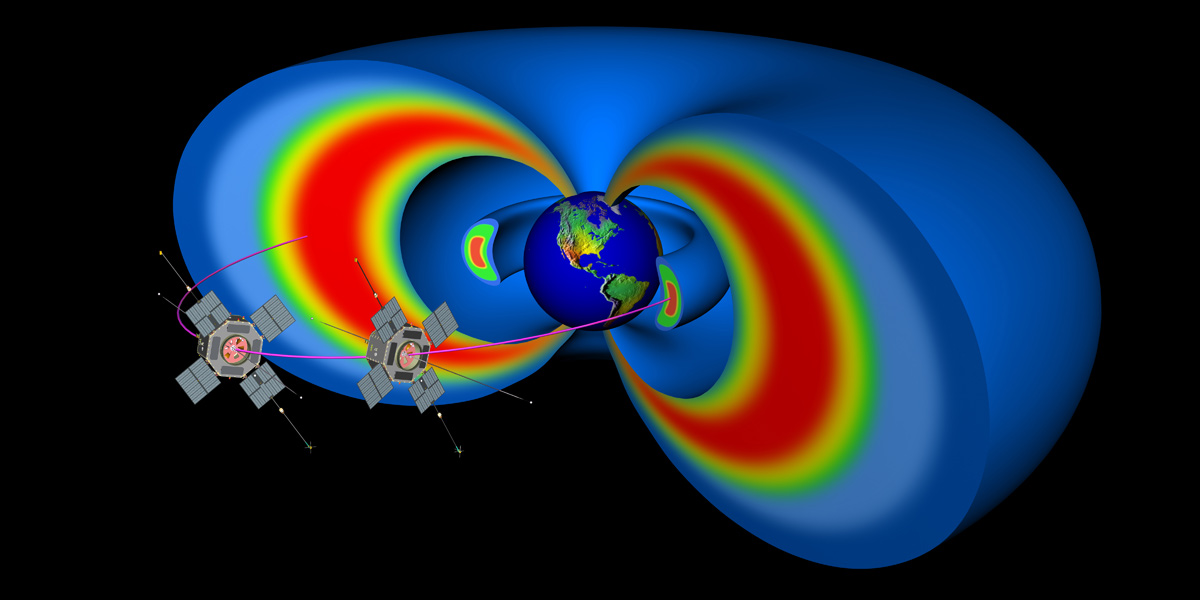

NASA's Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP) will fly through the thick belts of charged particles that encircle our planet to try to understand these dynamic environments. To withstand the damage such harsh radiation can inflict, the satellites are shrouded in strong layers of shielding.

The $670 million twin probes are due to launch aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket taking off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida at 4:08 a.m. on Aug. 23. They will take up two slightly different orbits through the Van Allen radiation belts, regions of protons and electrons spewed out from the sun that have been trapped by Earth's magnetic field.

The Radiation Belt Storm Probes launch is coming just weeks after one of NASA's most high-profile achievements in years: landing the huge Curiosity rover on Mars, which occurred Aug. 5 PDT.

"As cool as Mars is, it does not have a radiation belt," said Barry Mauk, RBSP project scientist based at Maryland's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), during a news briefing today (Aug. 9).

Radiation shields up!

To withstand the radiation, the spacecraft will "go there in a suit of armor" made of aluminum shielding a third of an inch thick (8.5 mm), said Rick Fitzgerald, RBSP project manager, also at APL. "That makes us one of the toughest missions." [Video: Probes to Study Radiation Threat to Astronauts]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And the spacecraft must achieve a complicated balancing act. While they need to protect themselves from the damaging solar radiation, they must also expose their instruments to it in order to make measurements. To do this, the RBSPs will allow radiation through small controlled openings.

Both satellites house five science instruments inside their eight-sided frames, which are about 6 feet across (1.8 m), 3 feet high (0.9 m), and weigh a total of 1,475 pounds (670 kg) each.

Mission managers have decided to launch two twin probes, instead of one, in order to take simultaneous readings at different locations, to determine whether a change in radiation levels indicates a change across time or across space.

Van Allen belt history

The Van Allen belts were discovered by American space scientist James Van Allen in 1958, but have remained largely mysterious.

"The dynamic is highly unpredictable. We know that variations in the sun cause geomagnetic storms," Mauk said. "The response of the radiation belts to those storms is highly variable. We just do not understand why that occurs."

The Radiation Belt Storm Probes will map out the density of charged particles across the belts, which are divided into two: an inner belt, and an outer. The inner belt normally extends from about 1,000 miles above Earth to 8,000 miles (1,600 to 13,000 kilometers). After a gap, the outer belt runs from around 12,000 to 25,000 miles (19,000 to 40,000 km).

"During solar storms, lots of things happen, the belts can expand greatly," said Mona Kessel, RBSP program scientist based at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C. "They can fill in the region between the belts and expand out."

When the belts expand, they can pose dangers to satellites orbiting Earth, and even the astronauts aboard the International Space Station, which orbits about 240 miles high (390 km).

"One satellite unfortunately could not unravel this complicated nature," Kessel added. "This is a job for RBSP."

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.