Invisible Dark Matter Likely Bountiful Near Sun

The area around our sun is probably rife with dark matter, the pervasive invisible stuff that populates the universe, a new study suggests.

Dark matter is thought to be all around us, making up a large fraction of the mass in the universe. Yet whatever particles compose dark matter interact so rarely with normal matter that we cannot shine light on it nor detect it through any means other than gravity.

While scientists have been fairly sure for decades that dark matter is common in galaxies and clusters of galaxies, experts have been unclear on just how prevalent it is in our immediate cosmic neighborhood.

Some past measurements have suggested the vicinity of our sun is chock-full of dark matter, while a 2011 study with new data predicted a relative dearth of the stuff near us. [Gallery: Dark Matter Throughout the Universe]

Now astronomers have used a new mass-measuring technique to tackle the problem. To test their method, the researchers tried it first on a simulation of our whole galaxy. The results suggested that this and other past methods have been undercounting dark matter, so the team adjusted their technique to correct for the bias.

They then applied their measurement algorithm to real data, using the known positions and velocities of thousands of orange K dwarf stars near the sun to estimate the density of invisible matter nearby.

The new calculation suggests that dark matter almost definitely exists around the sun, and there's a 90 percent chance it is more abundant than thought.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

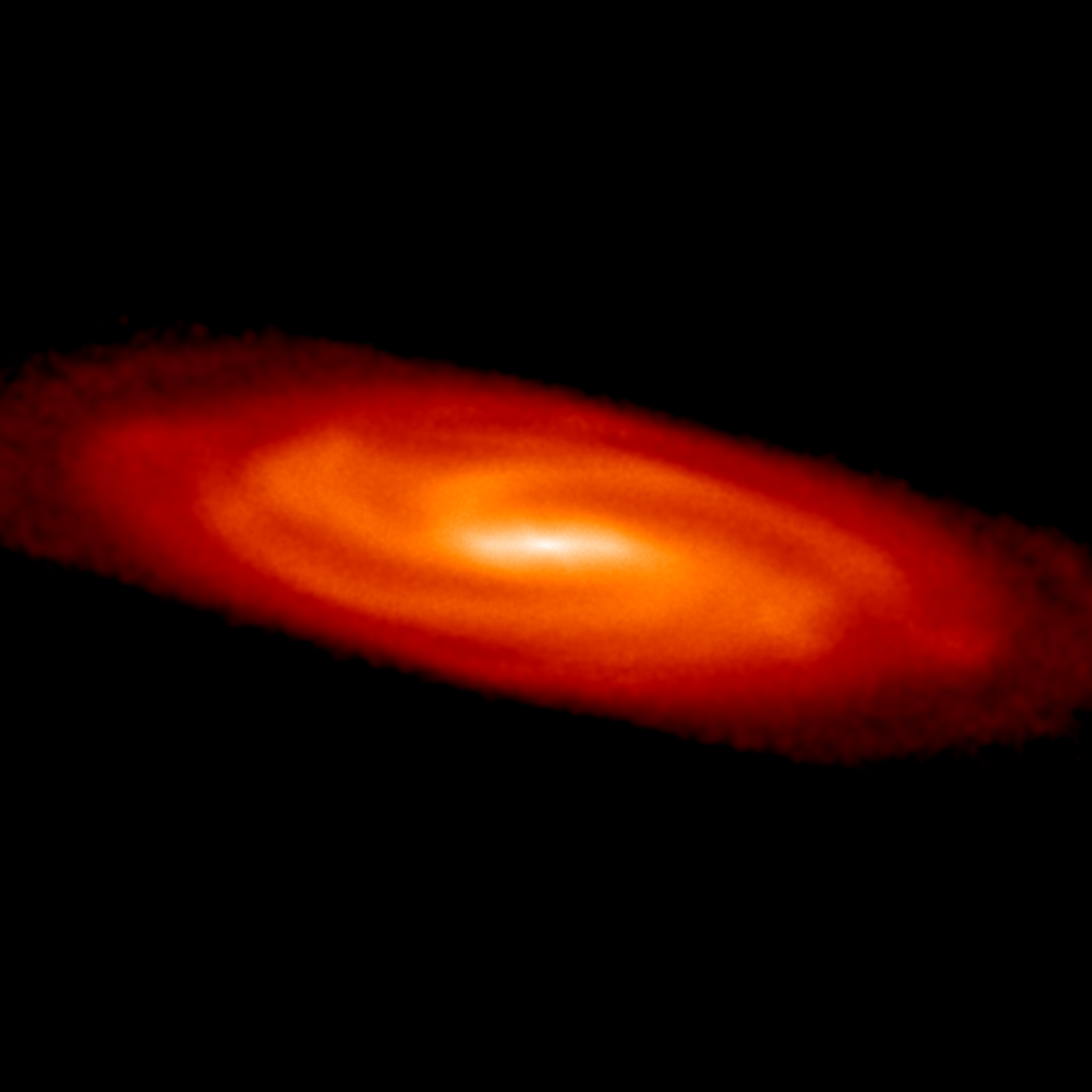

"If future data confirms this high value, the implications are exciting," study leader Silvia Garbari of the University of Zurich in Switzerland said in a statement. "It could be the first evidence for a 'disc' of dark matter in our galaxy, as recently predicted by theory and numerical simulations of galaxy formation. Or it could be that the dark matter halo of our galaxy is squashed, boosting the local dark matter density."

The mystery of dark matter could become clear if scientists could finally capture just a tiny bit of it. A number of detectors buried deep underground, in order to shield out all other particles, aim to catch dark matter on the extremely rare occasions dark particles might bump into normal matter particles. One such experiment, called XENON, is buried in Italy, while another, CDMS, is in Minnesota. So far, neither has found a reliable signal of dark matter.

"If dark matter is a fundamental particle, billions of these particles will have passed through your body by the time your finish reading this article," said the University of Zurich's George Lake. "Experimental physicists hope to capture just a few of these particles each year in experiments like XENON and CDMS currently in operation. Knowing the local properties of dark matter is the key to revealing just what kind of particle it consists of."

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.