NASA's Mars rover Curiosity will begin a "brain transplant" tomorrow (Aug. 11), a four-day operation that will bring a temporary halt to the robot's science activities.

Curiosity is getting a major update, switching over from software optimized for entry, descent and landing to programs designed to help the robot roam and study Red Planet rocks and soil, mission team members said.

The transition will involve both Curiosity's main and backup computers, and it should take four Martian days — or Sols, in mission lingo — to complete.

"This is primarily an engineering activity," Curiosity lead flight software engineer Ben Cichy, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., told reporters today (Aug. 10). "So we are mostly focusing on just getting done with the engineering and doing the installation, and standing down on science for the next four Sols." [Mars Rover Curiosity: 11 Amazing Facts]

A big switch

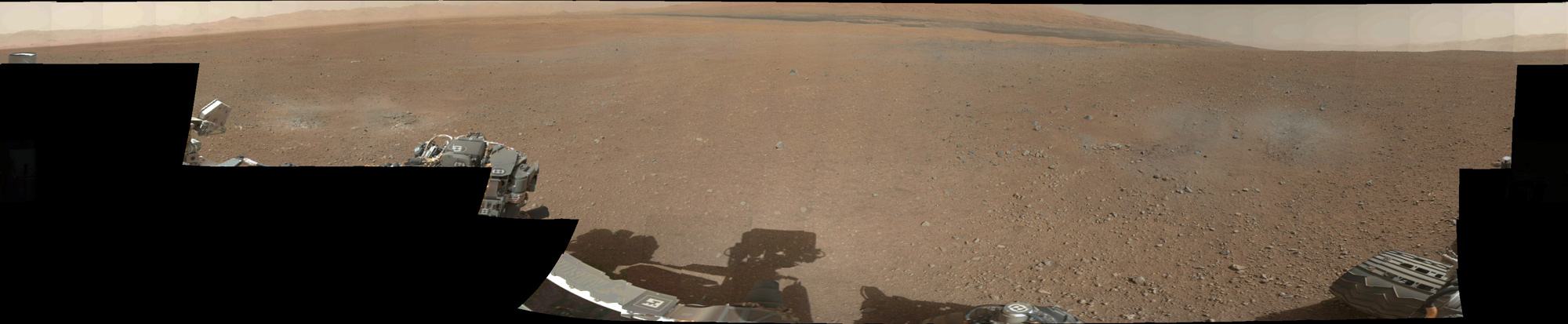

Curiosity, the centerpiece of NASA's $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory mission (MSL), touched down inside the Red Planet's huge Gale Crater late Sunday night (Aug. 5). It pulled off an unprecedented landing, during which a rocket-powered sky crane lowered the 1-ton rover to the surface on cables.

The MSL team calls the flight software that guided this daring touchdown R9. With Curiosity now safely on the surface, it's time to switch over to R10, which was uploaded during the rover's eight-month interplanetary cruise.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

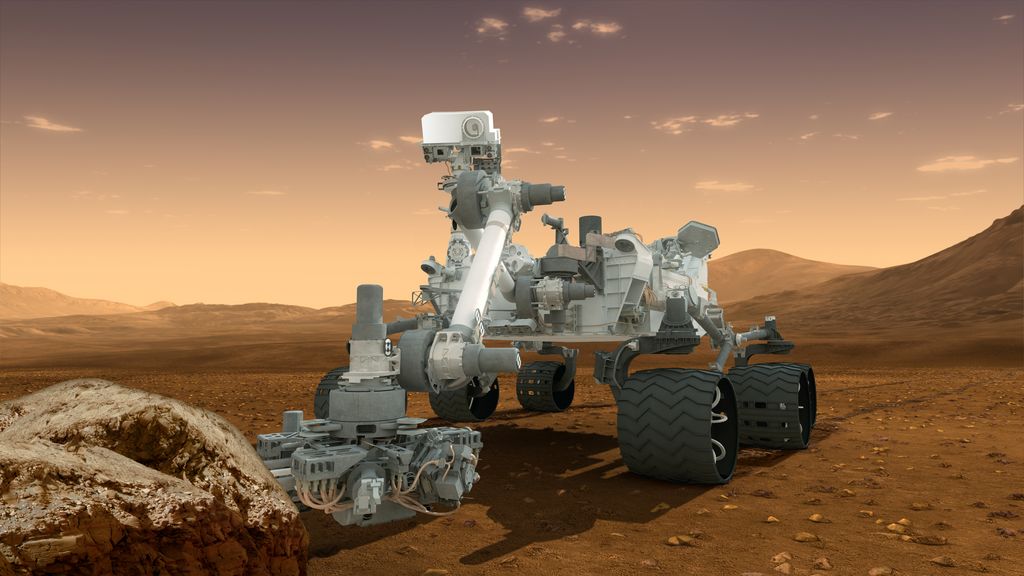

R10 will allow Curiosity to get the full use out of its 10 science instruments and its 7-foot-long (2.1 meters), drill-equipped robotic arm, Cichy said. And the software upgrade will let the six-wheeled robot roam — more or less autonomously, if its handlers wish — around the Gale Crater area.

"Curiosity was born to drive," Cichy said. "The R10 software includes the capability for Curiosity to really get out and stretch her wheels on the surface of Mars."

Software upgrades like this one are necessary in part because Curiosity's computing power is relatively low compared with what we're used to on Earth, a consequence of the tradeoffs required to toughen the rover up for the rigors of launch, flight, landing and Mars surface operations.

For example, Curiosity's two processors — one each in its main and backup computers — run at 133 megahertz, Cichy said. That's about 10 times slower than the processors found in typical smartphones. And the rover has about 4 gigabytes of storage capacity, compared with 64 gigs or so for a smartphone.

Transitioning to R10 frees up this limited computing power by taking the landing package out of the mix.

"It's like closing a few applications on your computer, and 'Wow, the whole thing runs faster, and now I can drive,'" Cichy said.

A four-day operation

The switch to R10 will take a while. It starts with a "toe dip" on Curiosity's main computer on Sol 5 (which itself begins around 7:30 p.m. PDT today [10:30 p.m. EDT; 0230 GMT Saturday]).

If everything looks good, the MSL team will commit to a full installation on Sol 6, Cichy said. The process will repeat on Sols 7 and 8 on Curiosity's backup computer.

Curiosity is slated to roam around the Gale Crater area for the next two years or more, attempting to determine if Mars can, or ever could, support microbial life. So a four-day halt on science activities doesn't amount to much in the grand scheme of the mission.

And R10 is worth the wait, Cichy said.

"It has a lot of great stuff that the science team wants, that the surface team wants, in order to enable this fantastic mission," he said. "And so that's why we're willing to spend some time here doing the install."

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.