NASA's Mars rover Curiosity may seem like the strong, silent type, but the 1-ton robot was making a lot of noise during its harrowing Red Planet touchdown on Aug. 5.

Curiosity phoned home throughout its daring and unprecedented landing sequence that night, giving its nervous handlers step-by-step status and health updates. The European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter recorded some of this chatter, and now we can hear what Curiosity had to say.

Sort of. ESA scientists have processed Curiosity's radio signals, shifting them to frequencies the human ear can hear.

"This provides a faithful reproduction of the ‘sound’ of the NASA mission’s arrival at Mars and its seven-minute plunge to the Red Planet’s surface," Mars Express researchers wrote in a blog post shortly after Curiosity's successful touchdown. [How Mars Rover's Landing "Sounded" (Video)]

The recording compresses about 20 minutes of Curiosity signals into a 19-second clip that sounds suitably otherworldly.

For a few seconds, it sounds as if a racecar is revving up its engine. Then that gives way to a strange electronic noise that calls to mind a 1980s video game — Pac Man, perhaps. The revving comes back, and then the recording stops.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mars Express was one of three spacecraft that stood by to observe Curiosity's landing, which saw the rover lowered to the surface on cables by a rocket-powered sky crane. NASA's Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) also kept tabs on Curiosity, the centerpiece of the $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory mission (MSL).

Mars' rotation took Curiosity out of direct contact with Earth a few minutes before it actually touched down, so NASA was counting on these spacecraft to relay news about how things went.

Mars Odyssey acted as a "bent pipe," sending Curiosity's signals on to mission control in real time and helping confirm the successful touchdown. (Because of the vast distance between Earth and Mars, the Curiosity team celebrated about 14 minutes after the rover actually landed.)

Both Mars Express and MRO must store information onboard for several hours before relaying it back to our planet, so they didn't break the big news on Aug. 5. And Mars Express' orbit took it out of range just before landing occurred.

"We tracked MSL for about 28 minutes, then lost contact as expected just a few moments before Curiosity’s touchdown in Gale Crater," Michel Denis, Mars Express Spacecraft Operations Manager, said in a statement. "NASA now have this valuable data, and everyone here is delighted to have helped support Curiosity’s arrival at Mars."

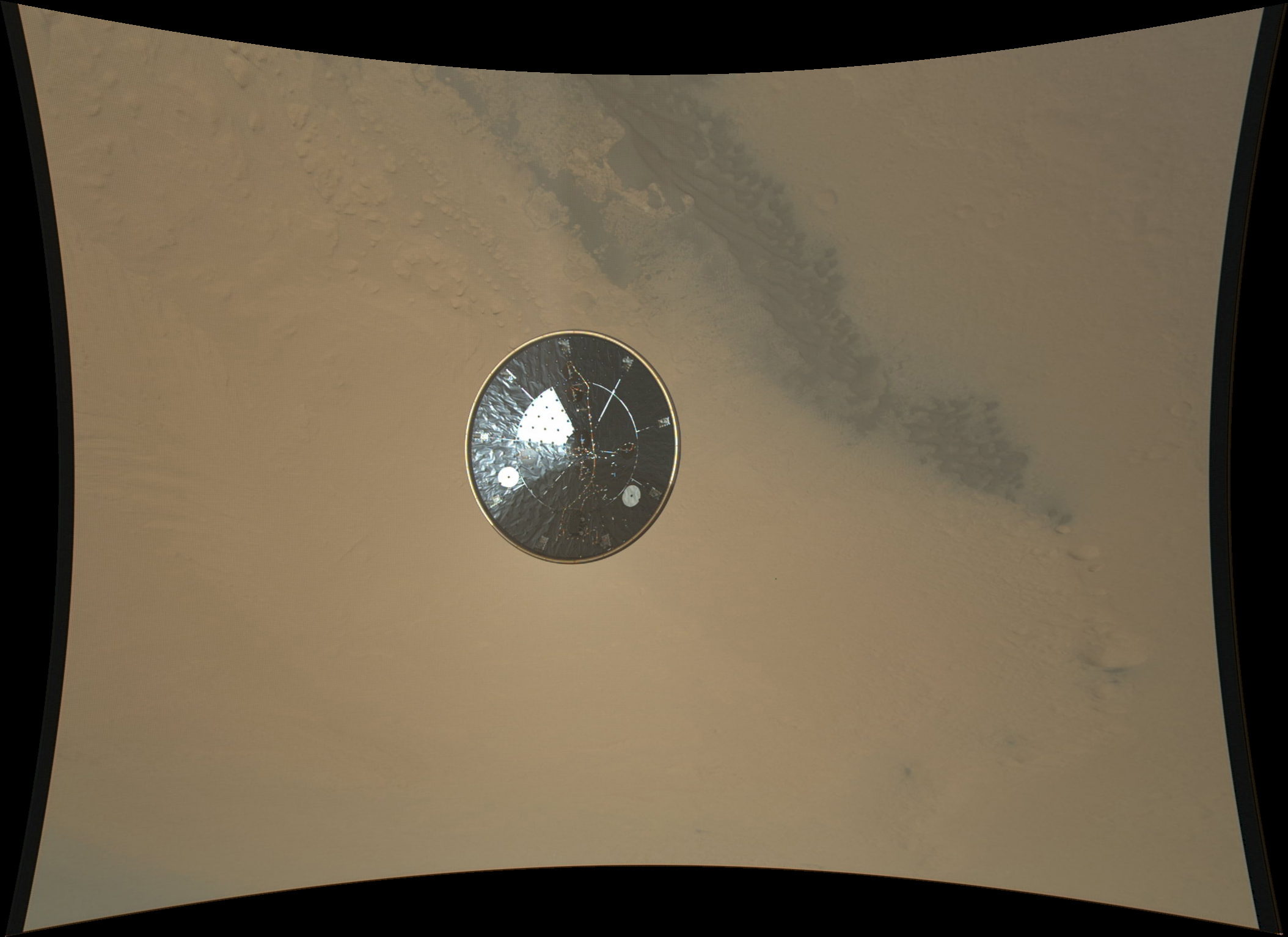

MRO, however, snapped a photo of Curiosity riding its parachute through the Martian atmosphere. The spacecraft has also captured images of the rover resting inside Gale Crater, and it spotted where Curiosity's sky crane, parachute, heat shield, backshell and ejected ballast came down.

Visit SPACE.com for complete coverage of NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.