The black hole that lies at the heart of our galaxy is much smaller than previously known. It could fit within the space between the Earth and the Sun, according to a new study.

Black holes are massive objects so dense that not even light can escape their gravitational pull.

Diameter estimates for one at the center of the Milky Way have ranged widely, from as small as the orbit of Mercury to as big as that of Pluto.

Last year, researchers estimated it was as wide as Earth's orbit around the Sun. The new estimate reduces that measurement by half, indicating the diameter of Sgr A*, as the object is known, is about 93 million miles -- same as the distance between Earth and the Sun.

The measurement was made using the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), a network of 10 radio telescopes spread out across the United States.

The finding is detailed in the Nov. 3 issue of the journal Nature.

Black kole or something else?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sgr A* is located at the center of the Milky Way Galaxy, about 26,000 light-years away. It is estimated to have a mass equal to about 4 million Suns. Such a high concentration of matter in such a small space places tight constraints on what the object could be if not a black hole.

An alternative possibility, though one not likely in the view of most theorists, is that the object might be a cluster of millions of collapsed dead stars, called neutron stars. If that were the case, the stars would only survive for about 20,000 years. At the end of that time, they would either collapse into black holes themselves or evaporate away into space.

The more likely alternative that Sgr A* is a supermassive black hole like those found at the centers of some other galaxies. Some of those black holes are more conspicuous, declaring their presence with highly visible streams of superheated matter, called particle jets.

While particle jets have been detected near Sgr A*, they have tended to be fainter and much shorter than those found around other supermassive black holes.

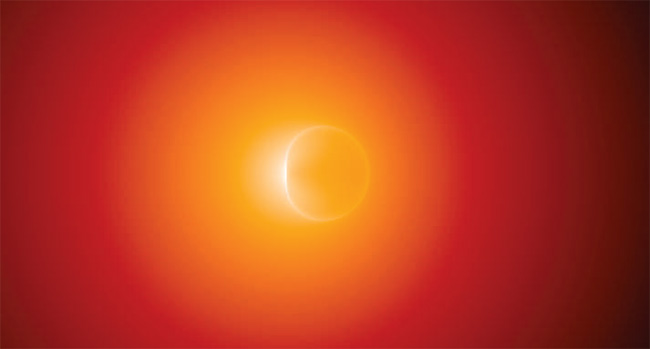

The new diameter measurements bring astronomers one step closer to detecting the theorized spherical region around a black hole that marks the boundary beyond which nothing-not even light-can escape the pull of gravity. This sphere is called the "event horizon," and detecting it would be the ultimate proof that Sgr A* is indeed a supermassive black hole.

Finding the event horizon

Event horizons have never been observed directly, but astronomers think they could be if a telescope's resolution was high enough. A sufficiently high-resolution image should reveal a dark circle-a "shadow"-caused by radiation from behind the black hole being sucked into the event horizon. Surrounding this shadow should be a bright ring of light caused by the deflection of light rays that just manage to scrape by the event horizon.

"Seeing that shadow would be the final proof that a supermassive black hole is at the center of our Galaxy," said Fred Lo, Director of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory and a researcher in the new study.

Such a shadow would be extremely faint and small from Earth, but could be detected if telescope resolutions could be improved to 1.5 times their current state, scientists say.

- Zeroing in on the Milky Way's Black Hole

- Astronomers Surprised: Stars Born Near Black Hole

- Scientists Pinpoint Milky Way Galaxy's Black Hole

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.