Supernova 'CSI' Team Eyes Old Photos for Stellar Blast Victim

In a forensic twist on astronomy, scientists turned sleuths are trying to track down the stellar victim of a supernova explosion that occurred last year.

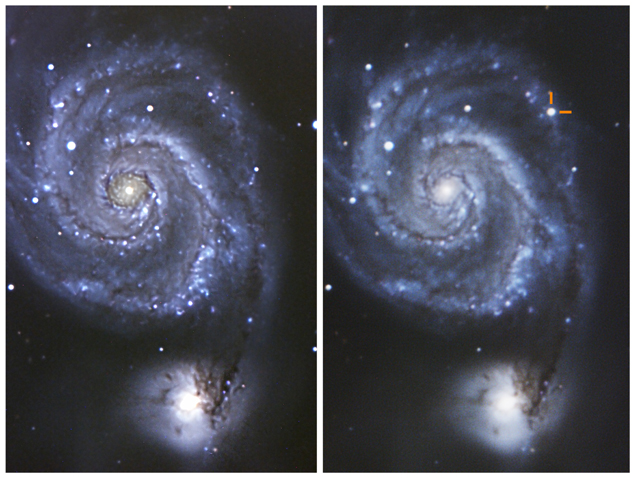

An exploded star was discovered on May 31, 2011, in the famous nearby Whirlpool Galaxy (M51), which lies about 23 million light-years from our own Milky Way. Supernovas are thought to occur when massive stars reach the end of their lives, running out of fuel to power their inner furnaces and collapsing in on themselves to form dense neutron stars or black holes.

This supernova, called SN 2011dh, peaked in brightness in June 2011, shining light across the universe that was picked up by telescopes here on Earth. Now, astronomers are going back to photos taken of the galaxy before the supernova to try to find the star that exploded.

Astronomers led by Melina Bersten of the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe in Japan say they've identified a yellow supergiant star, seen in Hubble Space Telescope photos taken before the explosion, very close to the location of the supernova. Furthermore, the team reports evidence that this star was in fact the progenitor of the explosion, and presents a model for how the star came to explode. [Supernova Photos: Great Images of Star Explosions]

The discovery is surprising, because yellow supergiants are not thought to be able to go supernova. This phase of star evolution is a short-term transition stage that stars usually pass through on their way to becoming red supergiants, which then are expected to explode at the end of their lives.

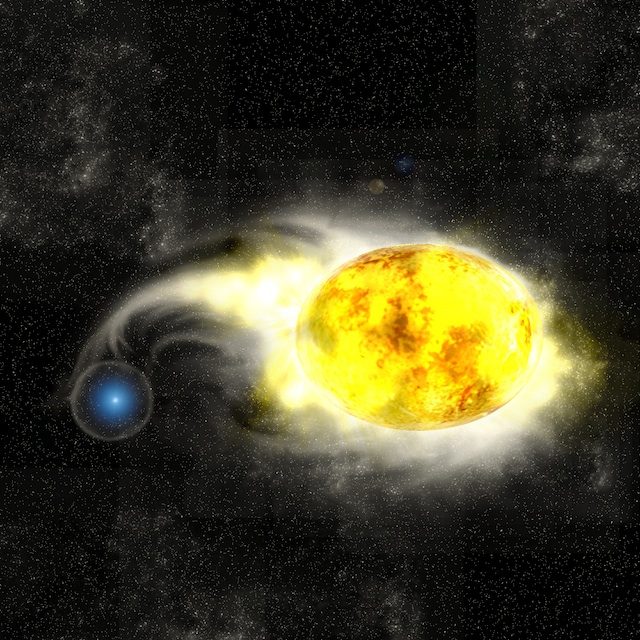

However, the researchers suggest that this star wasn't your average yellow supergiant. The scientists say the star might have been part of a binary system with a blue (hot) companion star that was siphoning off some of its mass. This process could have caused the star to become unstable and ultimately explode. Furthermore, this kind of interaction would have stripped the yellow supergiant's outer gaseous layers, leaving it in a condition that would have produced the light signature seen in the supernova if it did explode.

Additionally, the scientists calculated, based on hydrodynamic physics models, that whatever star gave rise to the supernova must have been an extended object with a radius compatible with that of a yellow supergiant.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The clincher to this theory would be to observe the blue companion star in photos taken before the supernova. No such star has yet been seen, but the scientists say that's not surprising: The companion would have emitted most of its light in the ultraviolet range, producing little visible light radiation for Hubble to see.

After the bright light from the supernova has faded, the astronomers hope to take follow-up observations in the ultraviolet spectrum to search for the star, which should still be in the same spot.

"The present results reveal the necessity and importance of further studying the evolution and explosion of binary stars," Bersten said in a statement. "I look forward to the observation that will confirm our prediction."

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.