An Old Idea Gives Telescopes A New Twist

Putting a new twist on an old idea, an inventor has designed a telescope instrument that could dramatically boost the ability of astronomers to find objects in space, even alien worlds.

It's called a Dittoscope, and while it sounds like a piece of copying technology from the 1970s, it's part of a decade-long effort by tinkerer and artist Tom Ditto.

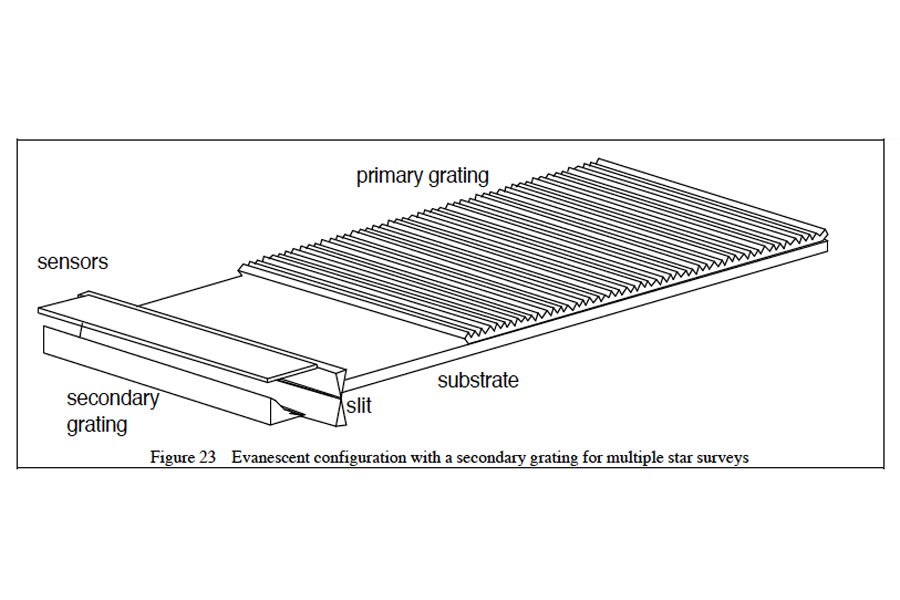

The Dittoscope is essentially a huge diffraction grating: a flat surface that is grooved in a regular pattern. (A cross-section would look like a series of regular waves.) Astronomers have used diffraction gratings for centuries. When the grating is hit by light, the waves bounce off at an angle nearly parallel to the surface of the grating. The light waves interfere with each other, and it's possible to see the different colors in the light. It's the reason CDs and even vinyl records give off rainbows when tilted at a certain angle.

What makes the Dittoscope different is that a parabolic collecting mirror set up at one end of the grating gathers the light and funnels it through a slit leading to a detector. Light passing through the slit strikes another diffraction grating to create an image.

That image shows stars with a band of colors superimposed over them. By looking at these bands of colors, or “spectra,” astronomers can tell what the stars are made of and determine whether they are is moving toward or away from Earth.

"I came up with this more by my ignorance than my training," Ditto, a 68-year-old New York native, told TechNewsDaily. He noted that there were some brief treatments of an idea like a Dittoscope that dated back a century. "In the 19th century therewas a primary objective grating telescope – what you would see in the eyepiece was the spectral lines,” he explained. “But you couldn't characterize them, they were too coarse. It was even worse if stars were close together."

Ditto’s solution was to add a slit for the light to go through after it hit the secondary collector, in this case the parabolic mirror.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

[Why Are Space Telescopes Better Than Earth-Based Telescopes?]

Not possible until now

Since a diffraction grating is basically a flat plane, it doesn't need any supporting structure. It doesn't even need to be that flat. That removes many of the size limits on ordinary telescopes, the biggest of which use gigantic structures to hold mirrors, which can weigh several tons.

The technology needed to make diffraction gratings that can be printed out in sheets wasn’t available when they were invented, but it is today. In one of his early prototypes, Ditto used the shiny material that goes on packages from an industrial supplier. "It wasn't a very good diffraction grating, but it worked," he said.

The Dittoscope also offers a wider field of view. A typical telescope sees a field of a few degrees or less; the Dittoscope can see a field of 40 degrees, capturing a much bigger chunk of sky on a given night.

Unlike a normal telescope, the Dittoscope would not have to track single objects. As a star passed over the grating, its spectrum would change as different wavelengths became visible. A computer program then could integrate the images to get a full spectrum.

Computers are another 20th-century technology that made Ditto's idea feasible. Before they were invented, putting together all the spectral data would have been impossible, since it involves thousands of wavelengths and thousands of objects in any one image.

The set-up — a large swath of sky and high resolution — would allow astronomers to get the spectra of more objects at one time. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey at Apache Point, N.M., has observed spectra of about 6,000 objects in a single night, more than any other observatory. A large Dittoscope could increase that by three orders of magnitude.

Ditto wrote up his first designs in 2002 and went to the SPIE conference, an annual meeting dedicated to optics and photonics. "I went to the few people responsible for spending $2 billion a year on telescopes and made my pitch," he said. In 2006 he got a NASA grant for $75,000 and built a small prototype, then a larger one. He now plans to submit his idea to the space agency again in 2013, where he will be competing for a grant of $500,000 over two years.

Ron Turner, senior science adviser to the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts, said Ditto's ideas are carefully thought out, which is why NASA approved the first round of funding and was willing to consider his proposals. "He's definitely an out-of-the-box thinker,” Turner said, “and a very good researcher … very meticulous and careful."

Alien world finder

Ditto thinks his invention could help NASA find planets around other stars. The space agency’s Kepler telescope spots alien worlds when they transit (that is, pass in front of) their stars, creating a dip in brightness. But any planets that don't happen to be in the line of sight don't get picked up. Another method is to see whether the stars "wobble" due to the gravitational pull of large, nearby planets.

The wobbles are usually detected by the Doppler shifts in spectra, but an astronomer has to decide which star to look at and get a reference picture, then check that against any changes over time.

The Dittoscope would save a step by providing a reference spectrum in one go.

For his part, Ditto thinks his idea could usher in a kind of Moore's law for astronomy. Some technologies, such as computer chips, change faster with time, but telescopes haven't. The 200-inch telescope at Mount Palomar was built in 1948, and the first telescope to double that was the Keck, built in 1993, a 45-year gap. The doubling of telescope sizes has slowed down and the basic designs are ones Isaac Newton would recognize, Ditto said.

That's because building a huge primary mirror is such a gigantic project. "I like to use the metaphor of whales and elephants," he said. "Animals in the water have buoyancy. Land animals can only be so big." The same thing applies to making mirrors — but not a diffraction grating. "Our primary [grating] could be a kilometer long."

This story was provided by TechNewsDaily, a sister site to SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.