Mariner 9: First Spacecraft to Orbit Mars

Mariner 9 was the first orbital mission to Mars. After arriving at the Red Planet in November 1971, imagery from Mariner 9 transformed our perception of Mars from a cold, crater-filled planet to a world full of past geological activity and a planet that once had water.

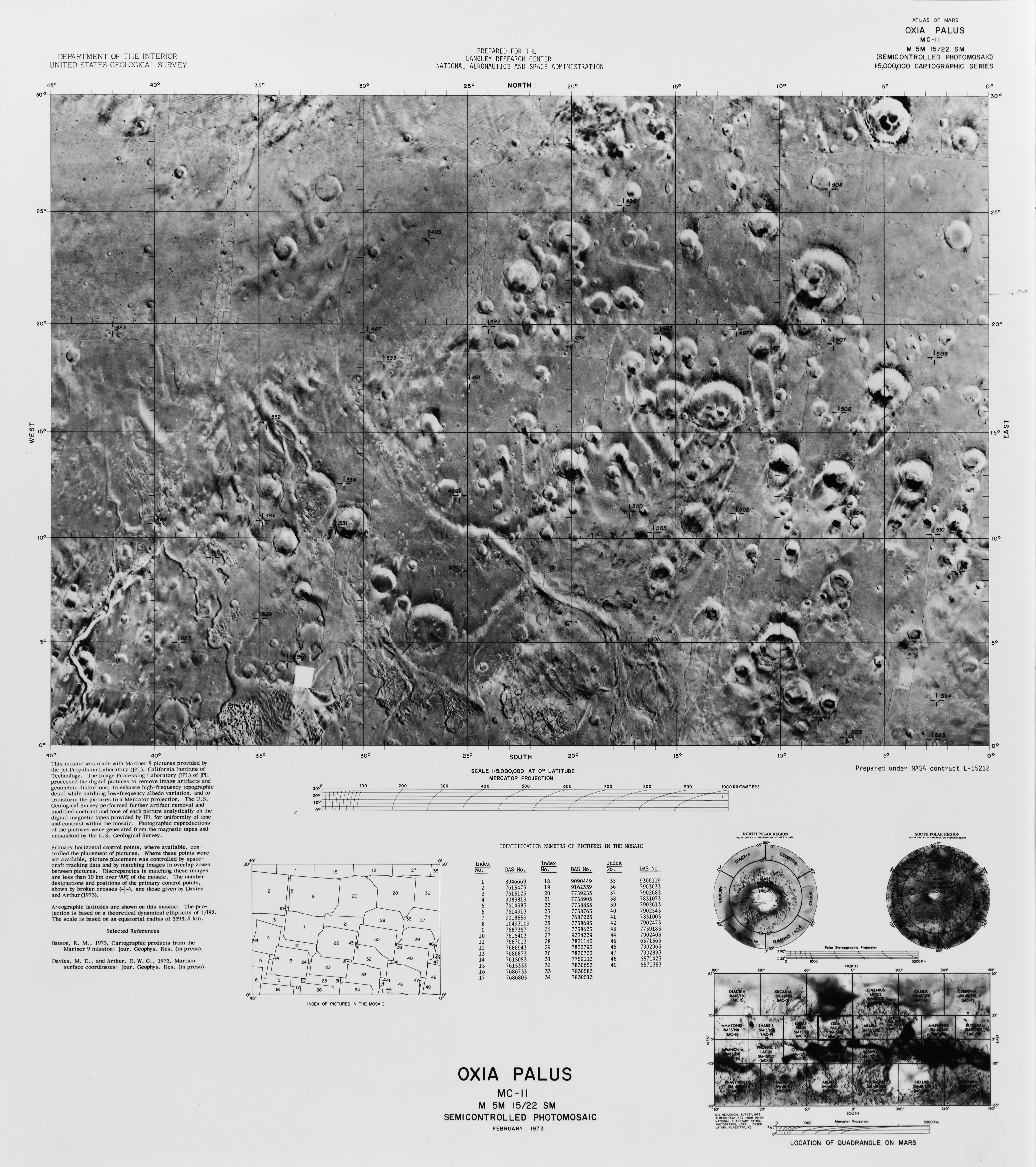

Mariner 9's cameras were the first to capture the gamut of Martian geology. The spacecraft's imagery included pictures of Mars' polar caps, the vast Valles Marineris canyon and the Martian moons (Phobos and Deimos). Marine 9 also discovered evidence that water had flowed on the planet in the ancient past.

An extended operation

NASA had sent spacecraft to Mars several times before, but those missions were relatively brief flybys.

In the early days of planetary exploration, the agency's strategy was to launch pairs of spacecraft to Mars so that there would be a backup if one of the spacecraft failed.

Mariner 4 was the first spacecraft to zip by Mars in 1965, and captured the first up-close images of a planet. Its twin spacecraft, Mariner 3, failed during launch.

Four years later, Mariners 6 and 7 paired up to fly above Mars within a few days of each other. Mariner 7 snapped a picture of Phobos, one of the Martian moons.

The missions were successful, but to reach a better understanding of the planet, longer-term observations were necessary. With more time, spacecraft could document the Red Planet's changing seasons, and take detailed measurements of the atmosphere, magnetic field and various surface features.

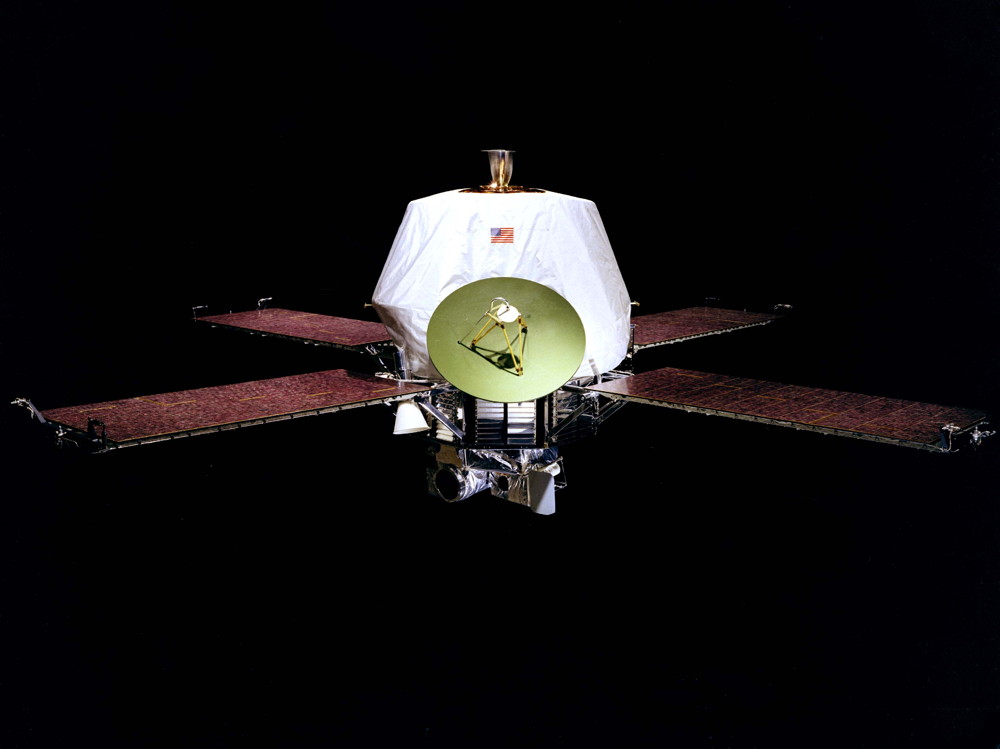

So, NASA added more weight and instruments to Mariners 8 and 9, which the agency planned to have orbit the planet. The spacecraft needed more fuel and required a more robust propulsion system for extended operations. Each spacecraft weighed more than Mariners 6 and 7 combined.

Mariner 8 lifted off on May 9, 1971, from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on a mission that lasted just 6 minutes. Due to a problem with the upper stage's main engine, the spacecraft arched over the Atlantic Ocean and crashed in the water about 350 miles (560 kilometers) north of Puerto Rico, according to NASA.

After Mariner 8's crash, NASA decided to send the Mariner 9 spacecraft aloft on an Atlas-Centaur rocket on May 30, 1971. Mariner 9 made it into space and set a course for the Red Planet.

Mars obscured

After 167 days flying in space, Mariner 9 reached Mars on Nov. 14, 1971. It fired its rocket for just over 15 minutes to put itself into orbit — a major accomplishment for NASA after the previous flyby missions.

In space, though, things rarely go as planned. Mariner 9 was ready to take pictures, but the planet was engulfed in a global dust storm. This itself was a discovery — astronomers had suspected these dust storms existed, but it was the first time they had seen them up close.

Still, it meant NASA had to wait to take pictures of the surface. Only the top of the massive Olympus Monsvolcano, as well as the three Tharsis volcanoes, could be seen peeking through the dust.

The dust began to clear in the coming weeks, settling down by January 1972. When the curtain lifted, it revealed a planet full of change and perhaps a colorful past.

"Some of the observed features included ancient river beds, craters, massive extinct volcanoes, canyons, layered polar deposits, evidence of wind-driven deposition and erosion of sediments, weather fronts, ice clouds, localized dust storms, morning fogs and more," NASA wrote in a summary of the mission.

Along with finding evidence of flowing water in the past, "the question of the existence of life on Mars was intensified," NASA wrote of Mariner 9.

"It was clear that Mars had brought about many more questions which a lander would be best suited to answer."

The spacecraft snapped 7,329 pictures and managed to image 80 percent of the Martian surface in less than a year, NASA said.

A vast canyon and other discoveries

Among Mariner 9's discoveries was a vast canyon stretching 2,500 miles (4,000 km) across the planet — nearly 10 times as long as the Grand Canyon — and reaching as deep as 4 miles (7 km). The massive rift extended a quarter of the way around Mars.

The feature was later named Valles Marineris, after its spacecraft discoverer. In the decades since, scientists have debated the canyon's origins.

At least one group of researchers believe Valles Marineris points to evidence of plate tectonics on Mars. A separate study looking at a nearby canyon suggested salts in the surface layers of Martian regolith collapsed when heated, opening a rift in the surface.

Mariner 9 also beamed back pictures of the Martian south pole, whose layers hinted that the Red Planet could have had different environments in the past.

NASA has kept a close eye on the pole in other missions. Mars Global Surveyor found evidence that carbon- dioxide deposits on the pole were shrinking. Mars Odyssey spotted vast tracts of water ice, and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter saw "dry ice" snowflakes falling from clouds near the pole.

Additionally, Mariner 9 shot pictures of apparent river beds winding their way across the surface. The spacecraft also captured relatively close-up views of the Mars moons Phobos and Deimos.

Mariner 9 showed researchers that Mars is a rapidly changing place. The mission helped point the way for future interesting science targets.

Legacy of Mariner 9

After almost a year in orbit, Mariner 9 ran out of attitude-control gas — the fuel necessary for controlling the spacecraft's orientation. NASA turned the spacecraft off on Oct. 27, 1972.

NASA expects Mariner 9 is orbiting high enough to keep flying around Mars until at least 2022 but at some point, the spacecraft will enter the atmosphere and crash to the planet's surface.

Mariner 9's orbiting mission was essential before sending a lander to Mars, said Donna Shirley, an aerospace engineer who worked on several NASA Mars efforts and is best known for managing the Pathfinder and Sojourner missions.

"If we had launched something to land in 1971, it would really have been silly. I mean, we didn't know much about the atmosphere," she said in a 2001 NASA oral histority interview.

"The Martian atmosphere varies a lot between summer and winter, much more than the Earth's atmosphere because it's thin and it gets puffed up very easily when it gets warmer and then collapses down in the winter," Shirley said. "So there were just enough uncertainties that doing an orbiter first was definitely the intelligent thing to do."

After Mariner 9

Mariner 9 paved the way for future Mars expeditions.

NASA program managers used pictures from Mariner 9 in planning the Viking 1 and Viking 2 landers, which both touched down successfully on Mars in 1976. For the past three decades, NASA has continued to send spacecraft to Mars.

Some of the more recent Mars missions include NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which arrived March 2006, found rock types formed by water as well as possible signs of flowing water on the surface; the Opportunity and Spirit rovers, which arrived in January 2004, found evidence of ancient water at their landing sites; and in August 2014 Curiosity landed on Mars and continues to explore Aeolis Mons (Mount Sharp) to follow the story of habitability and water on Mars. NASA also has orbiters at Mars called Mars Odyssey, which landed on Mars in October, 2001 and the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission (MAVEN), which landed in November, 2014. Mars InSight is scheduled to land on Nov. 26, 2018.

NASA isn't alone in its quest to explore the Red Planet, as several other space agencies have participated over the years. Some of the larger missions include Europe's Mars Express and India's Mars Orbiter Mission. Europe and Russia plan to launch their collaborative ExoMars rover in 2020, while NASA has planned to send its Mars 2020 rover to search for ancient organisms on the planet's surface.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.