What is Saturn Made Of?

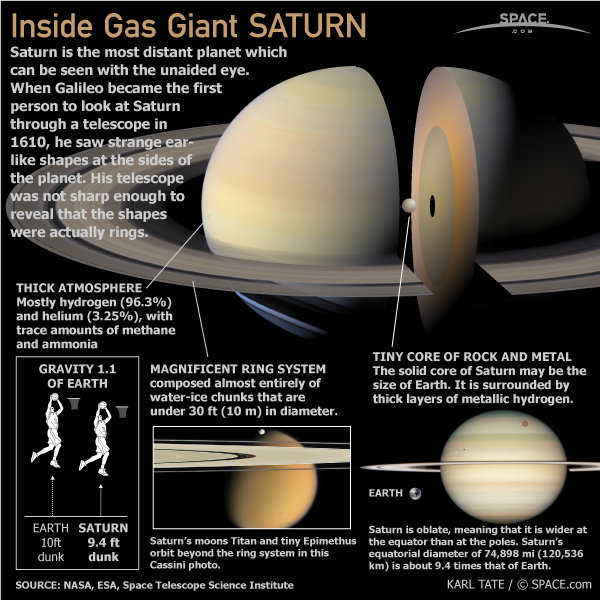

The gas giant Saturn contains many of the same components as the sun. Although it is the solar system's second largest planet, it lacks the necessary mass to undergo the fusion needed to power a star. Still, its gaseous composition — and the stunningly beautiful rings that surround it — make it one of the more interesting object in the solar system.

Saturn is predominantly composed of hydrogen and helium, the two basic gases of the universe. The planet also bears traces of ices containing ammonia, methane, and water. Unlike the rocky terrestrial planets, gas giants such as Saturn lack the layered crust-mantle-core structure, because they formed differently from their rocky siblings.

Saturn's surface

Saturn is classified as a gas giant because it is almost completely made of gas. Its atmosphere bleeds into its "surface" with little distinction. If a spacecraft attempted to touch down on Saturn, it would never find solid ground. Of course, the craft would be fortunate to survive long before the increasing pressure of the planet crushed it.

Because Saturn lacks a traditional ground, scientists consider the surface of the planet to begin when the pressure exceeds one bar, the approximate pressure at sea level on Earth.

Saturn's interior

At higher pressures, below the determined surface, hydrogen on Saturn becomes liquid. Traveling inward toward the center of the planet, the increased pressure causes the liquefied gas to become metallic hydrogen. Saturn does not have as much metallic hydrogen as the largest planet, Jupiter, but it does contain more ices. Saturn is also significantly less dense than any other planet in the solar system; in a large enough pool of water, the ringed planet would float.

Like Jupiter, Saturn is suspected to have a rocky core surrounded by hydrogen and helium. However, the question of how solid the core might be is still up for debate. Though composed of rocky material, the core itself may be liquid.

The distance to Saturn from the sun is significant, keeping the average temperature of Saturn low, but things are hotter within the rocky core. There, temperatures can reach as high as 21,000 degrees Fahrenheit (11,700 degrees Celsius).

During the formation of Saturn, the core would have been created first. Research suggests that Saturn's rocky core is between 9 to 22 times the mass of Earth. Only when it reached sufficient mass would the planet have been able to gravitationally pile on the light hydrogen and helium gas that make up most of the its mass.

A strong magnetic field

As on Jupiter, the liquid metallic hydrogen drives the magnetic field of Saturn. Saturn's magnetosphere is smaller than its giant sibling, but still significantly more powerful than those found on the terrestrial planets. With a magnetosphere large enough to contain the entire planet and its rings, Saturn's magnetic field is 578 times as powerful as Earth's.

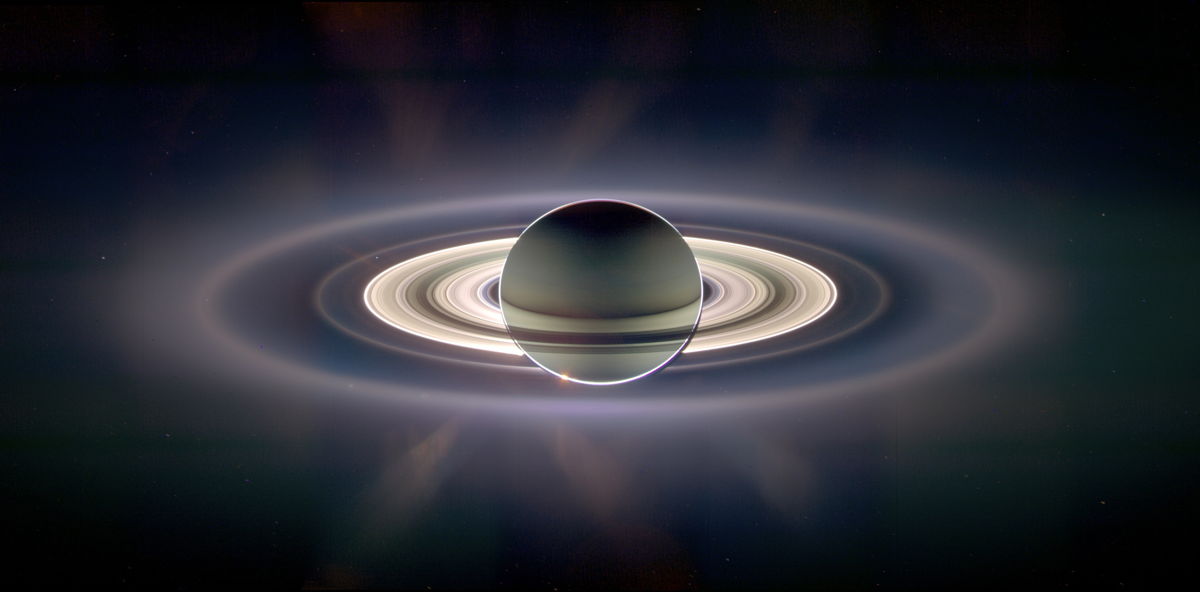

The rings of Saturn

When Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei turned his telescope toward Saturn, he observed two blobs on either side that he identified as bodies separate from the main planet. It wasn't until Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens studied the planet with a more powerful scope that the rings of Saturn were first identified.

Although most of the gas giants boast rings of some sort, Saturn's are the largest and arguably the most visually stunning. Stretching as far out as 262,670 miles (422,730 km), or eight times the radius of the planet, the rings are made up of ice and rock pieces that create a rainbow effect as they refract the light from the sun. [PHOTOS: Saturn's Glorious Rings Up Close]

— Nola Taylor Redd, SPACE.com Contributor

Related:

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd