What is Uranus Made Of?

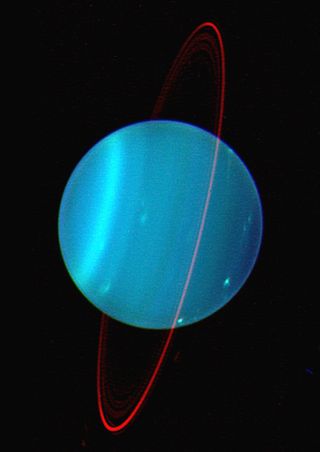

Far, far from the sun, Uranus has a blue-green atmosphere that hints at its makeup. One of the two ice giants, the planets composition differs somewhat from Jupiter and Saturn in that it is made up of more ice than gas.

"Uranus and Neptune are really unique in our solar system. They're very different planets than the other ones we think of," planetary scientist Amy Simon said on NASA's Gravity Assist podcast. "Part of the reason we call them ice giants is because they actually have a lot of water ice. So, while some of the other gas giant planets are mostly hydrogen and helium, they're predominately water and other ices."

The surface of Uranus

Like the other gas giants, Uranus lacks a solid, well-defined surface. Instead, the gas, liquid, and icy atmosphere extends to the planet's interior. Were you to land — and hover — at the point where the atmosphere transitions to the interior, you would experience less of a gravitational tug than you might feel on Earth. Gravity on Uranus is only about 90 percent that of Earth; if you weigh 100 lbs. at home, you would only weigh 91 lbs. on Uranus.

"I think poor Uranus is misunderstood, actually," planetary scientist Amy Simon said on NASA's Gravity Assist podcast. "Uranus is very bland in appearance most of the time. It's kind of a pale blue planet. It's the real pale blue dot."

Uranus is the second least dense planet in the solar system, indicating that it is made up mostly of ices. Unlike Jupiter and Saturn, which are composed predominantly of hydrogen and helium, Uranus contains only a small portion of these light elements. It also houses some rocky elements, equal to somewhere between 0.5 to 1.5 times the mass of Earth. But most of the planet is made up of ices, mostly water, methane, and ammonia. Ices dominate because the vast distance to Uranus from the sun allows the planet to maintain frigid temperatures.

A frigid core

While most planets have rocky molten cores, the center of Uranus is thought to contain icy materials. The liquid core makes up 80 percent of the mass of the planet, mostly comprised of water, methane, and ammonia ice, though it only extends to about 20 percent of the radius.

The internal heat of Uranus is lower than astronomers would expect. The planet's core heats up to 9,000 degrees Fahrenheit (4,982 degrees Celsius). This seems hot, but is in fact pretty cool when compared to the cores of other planets. According to Simon, Uranus is the only world that doesn't give off more heat from its core than it receives from the sun.

While other gas giants are powered by their cores, Uranus radiates almost no excess heat into space. One reason for this could be due to an impact soon after the planet's formation. The planet's current sideways rotation, spinning at a 90-degree angle compared to the other planets in the solar system, already indicates a collision. The impact could also have carved out a portion of the core, leaving it with a lower temperature.

A strange magnetic field

Movement inside of the core tends to drive a planet's magnetic field, but the field around Uranus is strange. Fairly weak, no indication of a field was recorded until NASA's Voyager 2 arrived at the planet in 1986.

Generally, a magnetic field shrouds the planet from its poles. On Earth, for instance, the geographic North Pole is very close to the magnetic North Pole. But Uranus, discovered in 1781, is tipped on its side, so that one pole or the other is pointed almost directly at the sun. The planet's magnetic field is offset from the poles by almost 60 degrees, creating a magnetic field that tends to be stronger at one pole than the other.

Although the magnetic field of Uranus is strange, it is not unique. Neptune, the other ice giant, boasts a similar magnetic field, leading astronomers to conclude that the core may not drive the fields.

"If you could think about two magnets crossed with each other, it's almost like that," Simon said. "It's really strange."

In 2017, researchers found that the magnetic field around the ice giant may have an odd, strobe-like effect. Every time the planet rotates (about every 17.24 hours), the lopsided field tumbles about, opening and closing as the magnetic fields disconnect and reconnect.

"Uranus is a geometric nightmare," Carol Paty, an associate professor at Georgia Tech's School of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences and co-author of the study, said in a statement. "The magnetic field tumbles very fast, like a child cartwheeling down a hill head over heels. When the magnetized solar wind meets this tumbling field in the right way, it can reconnect, and [so] Uranus' magnetosphere goes from open to closed to open on a daily basis."

Rocky rings

Like all gas giants, Uranus carries a set of rocky rings around its equator. The thin strips, most only a few miles wide, are made up of tiny bits of rock and ice smaller than a meter. The planet has at least 13 known rings in two systems.

Uranus' outermost ring shines a bright blue. Saturn is the only other world in the solar system with a blue ring. The blue rings of both worlds are associated with moons, Saturn with Enceladus and Uranus with Mab.

"The outer ring of Saturn is blue and has Enceladus right smack at its brightest spot, and Uranus is strikingly similar, with its blue ring right on top of Mab's orbit," Imke de Pater, professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a 2006 statement.

Waves in the ring hint that the planet may have more than the 27 known moons.

"At the edges of the rings … it's almost like the amount of stuff is going up and down in a periodic fashion that looks kind of like a wave, with crests and troughs," then-graduate student Robert Chancia, of the University of Idaho, told Space.com. "It seems consistent with something disturbing the rings there," he added.

"Based on the amplitude of this wave pattern and that distance from the ring … and our attempts to find the moon in images, it basically points toward if they exist, they're pretty tiny," Chancia said. He estimated that the moons, if they exist, are likely smaller than 3 miles (5 kilometers) in radius.

In addition to pointing toward potentially unseen moons, the thin rings of narrow can also help researchers to understand more about the planet.

"Rings are great because they're one way that we actually can do kind of the equivalent of seismology on the planets," Simon said. "We can look at how the rings oscillate and how their shapes change and learn a little bit about the inside of the planets."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook, or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd