Strange But True: Astronauts Get Taller in Space

Astronauts in space can grow up to 3 percent taller during the time spent living in microgravity, NASA scientists say. That means that a 6-foot-tall (1.8 meters) person could gain as many as 2 inches (5 centimeters) while in orbit.

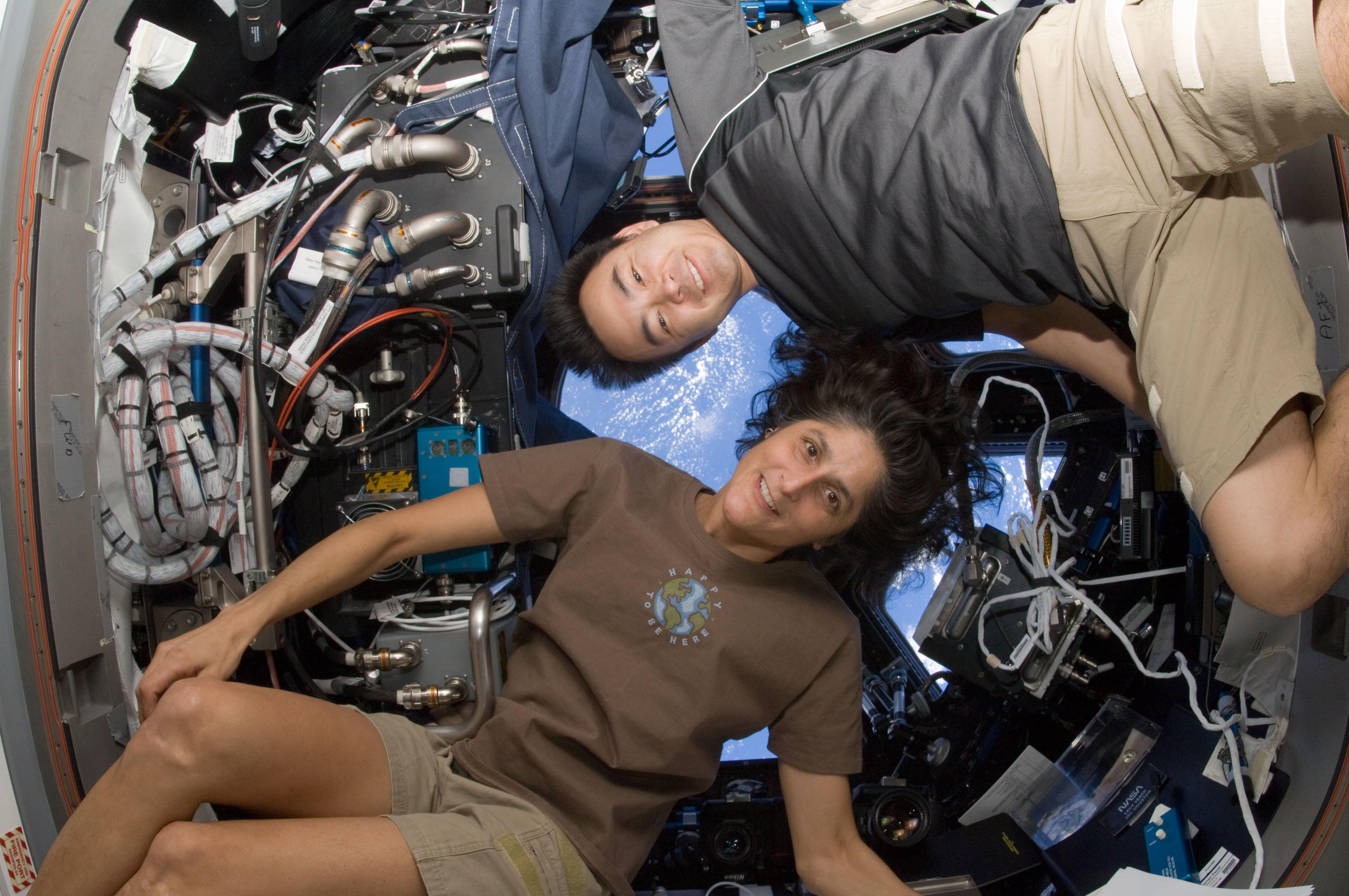

While scientists have known for some time that astronauts experience a slight height boost during a months-long stay on the International Space Station, NASA is only now starting to use ultrasound technology to see exactly what happens to astronauts' spines in microgravity as it occurs.

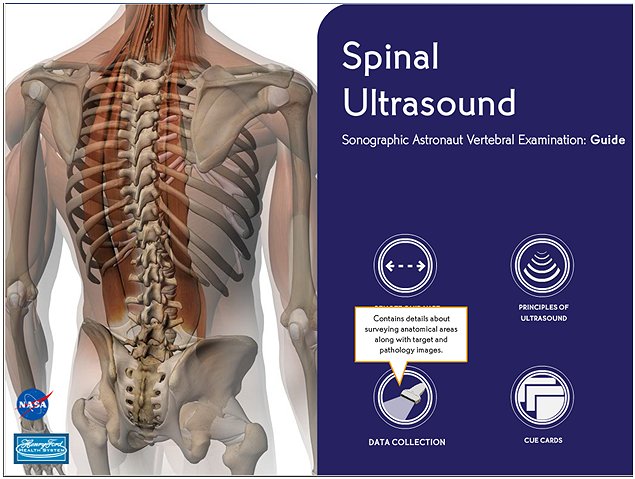

"Today there is a new ultrasound device on the station that allows more precise musculoskeletal imaging required for assessment of the complex anatomy and the spine," the study's principal investigator Scott Dulchavsky said in a statement. "The crew will be able to perform these complex evaluations in the next year due to a newly developed Just-In-Time training guide for spinal ultrasound, combined with refinements in crew training and remote guidance procedures."

A better understanding of the spine’s elongation in microgravity could help physicians develop more effective rehabilitation techniques to aid astronauts in their return to Earth’s gravity following space station missions. [Quiz: The Reality of Life in Space]

Past studies have shown that when the spine is not exposed to the pull of Earth's gravity, the vertebra can expand and relax, allowing astronauts to actually grow taller. That small gain is short lived, however. Once the astronauts return to Earth, their height returns to normal after a few months. But still, scientists haven't been able to examine the astronaut's spinal columns when experiencing the effects of microgravity until now.

This month, astronauts will begin using the ultrasound device to scan each other's backs to see exactly what their spines look like after 30, 90 and 150 days in microgravity. Researchers will see the medical results in real time as the astronaut take turns scanning their spines of their crewmates.

Astronauts typically visit the space station in six-month increments, allowing for long-term studies of how the human body changes over time in microgravity.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Ultrasound also allows us to evaluate physiology in motion, such as the movement of muscles, blood in vessels, and function in other systems in the body," Dulchavsky said. "Physiological parameters derived from ultrasound and Doppler give instantaneous observations about the body non-invasively without radiation."

Astronauts typically visit the space station in six-month increments, allowing for long-term studies of how the human body changes over time in microgravity.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter @mirikramer or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.