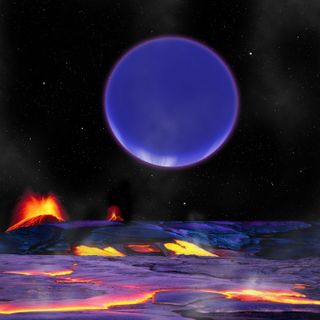

Alien Earth: What It Will Mean to Find Our Planet's Twin

LONG BEACH, Calif. — Finding Earth 2.0 is just a matter of time, and the discovery will likely transform the way we think about our place in the cosmos, astronomer Natalie Batalha said Tuesday (Jan. 8).

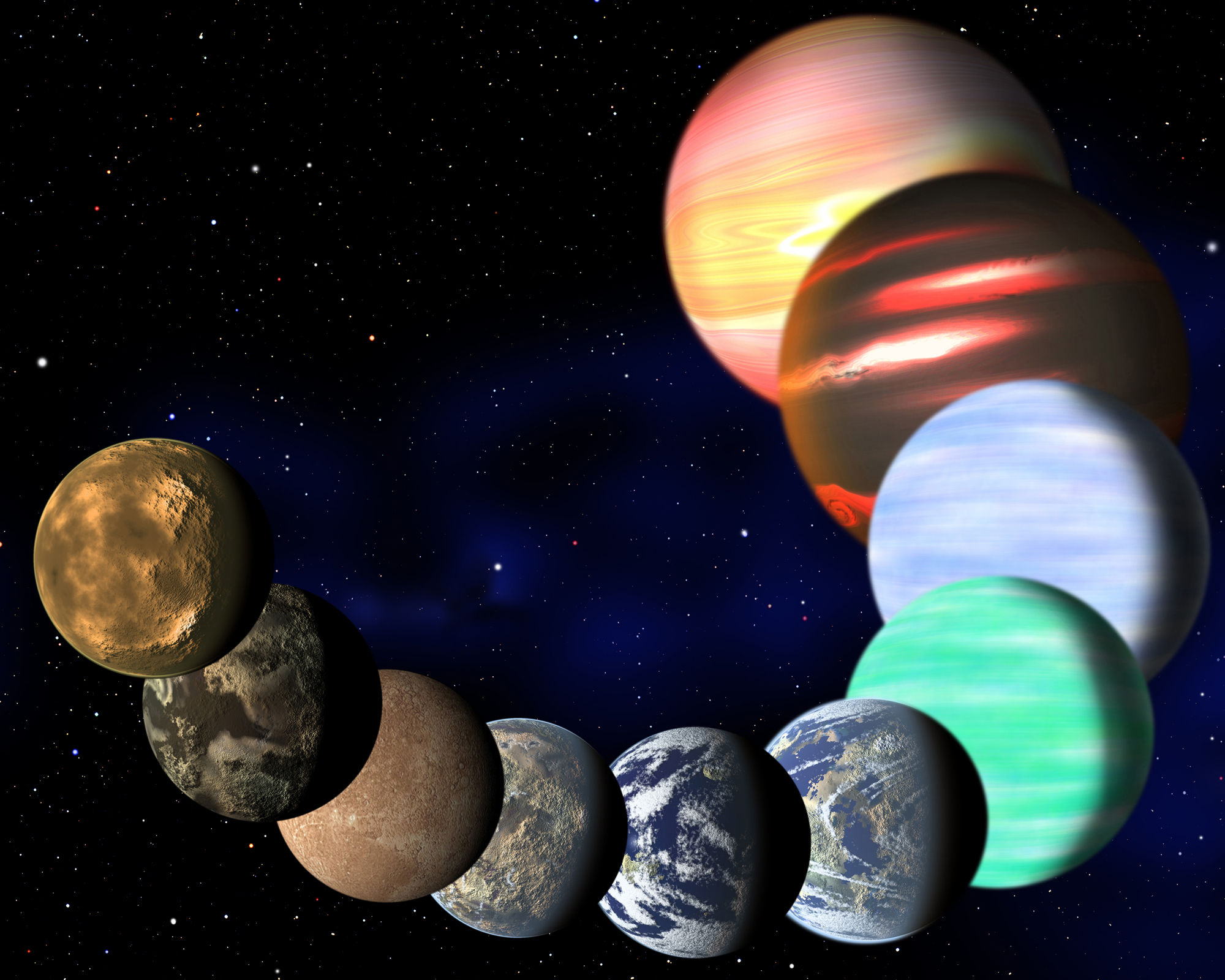

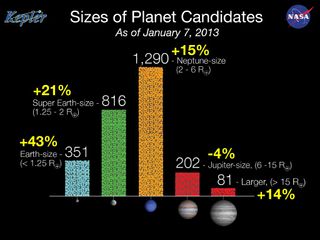

Batalha is a co-investigator for NASA's Kepler telescope, a planet-hunting mission that has uncovered 2,740 potential alien worlds in just the few years since its 2009 launch. Though Kepler has found some Earth-size planets, and others in the habitable zones around their stars that could allow them to harbor liquid water, none of them are true Earth twins. But that's likely soon to come.

"That is certainly the big picture goal, that is what NASA is aiming to do, to find the next Earth and ultimately to find other life in the galaxy," Batalha said here at the 221st meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

However, Kepler itself isn't ideally equipped to find Earth-size planets orbiting sun-like stars at roughly the same distance of our world from the sun.

"We wouldn't probably recognize it if we did see it," Batalha said. "We wouldn’t know about the atmosphere, we might not even know about the mass. The question Kepler is designed to answer is, 'what is the fraction of stars in our galaxy that harbor potentially habitable Earth-size planets?' It's a statistical mission."

Nonetheless, Kepler is laying the vital groundwork for future missions to follow-up on to identify not just one, but potentially many planets that strongly resemble our own home in the cosmos, she said.

Close but no cigar

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So far, Kepler has found 351 roughly Earth-size planet candidates, plus 58 possible planets in their stars' habitable zones. Some of these are what are called "Super Earths," just a tad larger than our own planet. And one exciting Kepler find, called KOI 172.02, is a Super Earth in the habitable zone orbiting a star very much like our sun.

Furthermore, studies suggest small planets like Earth are probably common in the universe. One estimate suggests the tally could be 17 billion Earth-size planets in our own galaxy alone. [17 Billion Earths Fill Our Milky Way Galaxy (Infographic)]

"Nature likes to make small things efficiently," Batalha said. "It plays out for stars, it plays out in the solar system. Why not for exoplanets?"

All of these signs point toward a discovery of an Earth-twin beyond the solar system in the near future — likely sometime this year, experts say.

And when we do find the first world out there like our own, it will change the way many think of our place in the universe. If our planet isn't unique, why should life there be unique, either?

Batalha said Kepler has already changed her view of the cosmos.

"One night I was running home," the astronomer, who likes to run in the evenings, told SPACE.com, "and it was a particularly clear night so it was a nice starry sky, and in that split second when I looked up at the stars I saw the sky differently. I saw not just pinpoints of light; I saw solar systems. It was really a fundamental paradigm shift for me. I think everybody will experience that once they know there are so many planets out there."

The first discovery of a second Earth will likely be another watershed moment for her and many, she said.

"An Earth analogue has different implications," she said. "What it makes everybody think about is life. That is the long-term goal."

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.