What Will First Photos of Black Holes Look Like?

A giant black hole is thought to lurk at the center of the Milky Way, but it has never been directly seen. Now astronomers have predicted what the first pictures of this black hole will look like when taken with technology soon to be available.

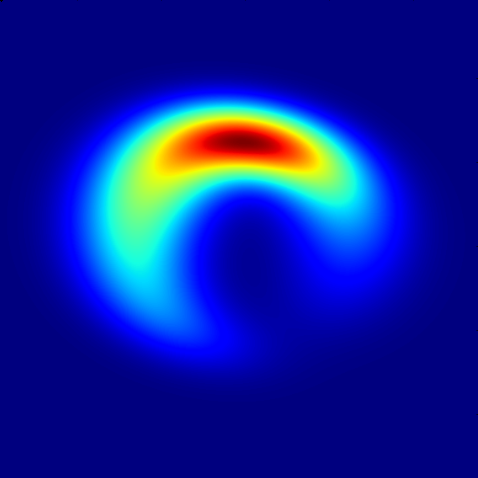

In particular, researchers have found that pictures of a black hole ― or, more precisely, the boundaries around them ― will take a crescent form, rather than the blobby shape that is often predicted.

By modeling what these pictures will look like, scientists say they are preparing to interpret the photos that will become available from telescopes currently under construction.

"No one has been able to image a black hole," said University of California, Berkeley student Ayman Bin Kamruddin, who presented a poster on the research last week in Long Beach, Calif., at the 221st meeting of the American Astronomical Society. "So far it's been impossible because they're too small in the sky. Right now we're just getting some details about the structure, but we don't have an image yet." [Gallery: Black Holes of the Universe]

Black holes themselves are invisible, of course, as not even light can escape their gravitational clutches. However, the boundary of a black hole — the point of no return called the event horizon — should be visible from the radiation emitted by matter falling into the black hole.

"A black hole's immediate surroundings have a lot of really interesting physics going on, and they emit light," Kamruddin said. "Technically speaking, we aren't exactly seeing the black hole, but we are effectively resolving the event horizon."

A new project called the Event Horizon Telescope combines the resolving power of numerous antennas from a worldwide network of radio telescopes to sight objects that otherwise would be too tiny to make out.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The Event Horizon Telescope is the first to resolve spatial scales comparable to the size of the event horizon of a black hole," said Kamruddin's collaborator, University of California, Berkeley astronomer Jason Dexter. "I don't think it's crazy to think we might get an image in the next five years."

The Event Horizon Telescope already has been gathering some preliminary measurements of the object called Sagittarius A* (pronounced "Sagittarius A-star") at the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

Kamruddin and Dexter have matched this data to various physical models and found that they best fit images that are crescent-shaped, rather than the blob shapes called "asymmetric Gaussians" that had been previously used in models.

The crescent shape emerges from the flat doughnut, called an accretion disk, formed by matter orbiting a black hole on its way to falling in. As gas spins around the black hole, one side of the disk comes toward view on Earth, and its light becomes brighter because of a process called Doppler beaming. The other side, representing receding gas, gets dimmer because of this effect.

"There's really extreme bending of light happening because of general relativity and the extremely strong gravitational field," Kamruddin said.

Knowing that the crescent model best fits the data allows the researchers to discriminate between different models describing the physics around the black hole. Ultimately, the astronomers hope to use the first photos of Sagittarius A* to accurately weigh the behemoth at the center of the Milky Way.

"Just getting an image itself will be mind-blowing," Kamruddin said. "It will provide direct confirmation of the event horizon, which has been predicted, but no one's ever actually seen it. Seeing what it is like will rule out certain physics."

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.