Space Explosion to Blame for Tree Ring Mystery, Astronomers Say

More than 1,200 years ago, some mysterious event was recorded in tree rings in a Japanese cedar forest.

While one study suggested a solar flare was to blame, a new group of researchers are pointing toward a gamma-ray burst, a powerful space explosion.

The ancient cedar trees record a rare event around 774 or 775 A.D. This shows up in a sharp rise in the amount of radioactive carbon-14 and beryllium-10 recorded in the trees' rings, which can be created by incoming particles from space.

But what caused an influx of radiation?

Tree ring mystery

According to astronomers Valeri Hambaryan and Ralph Neuhauser of the Astrophysics Institute of the University of Jena in Germany, the most likely culprit was a gamma-ray burst. [Amazing Solar Flare of Oct. 22, 2012 (Photos)]

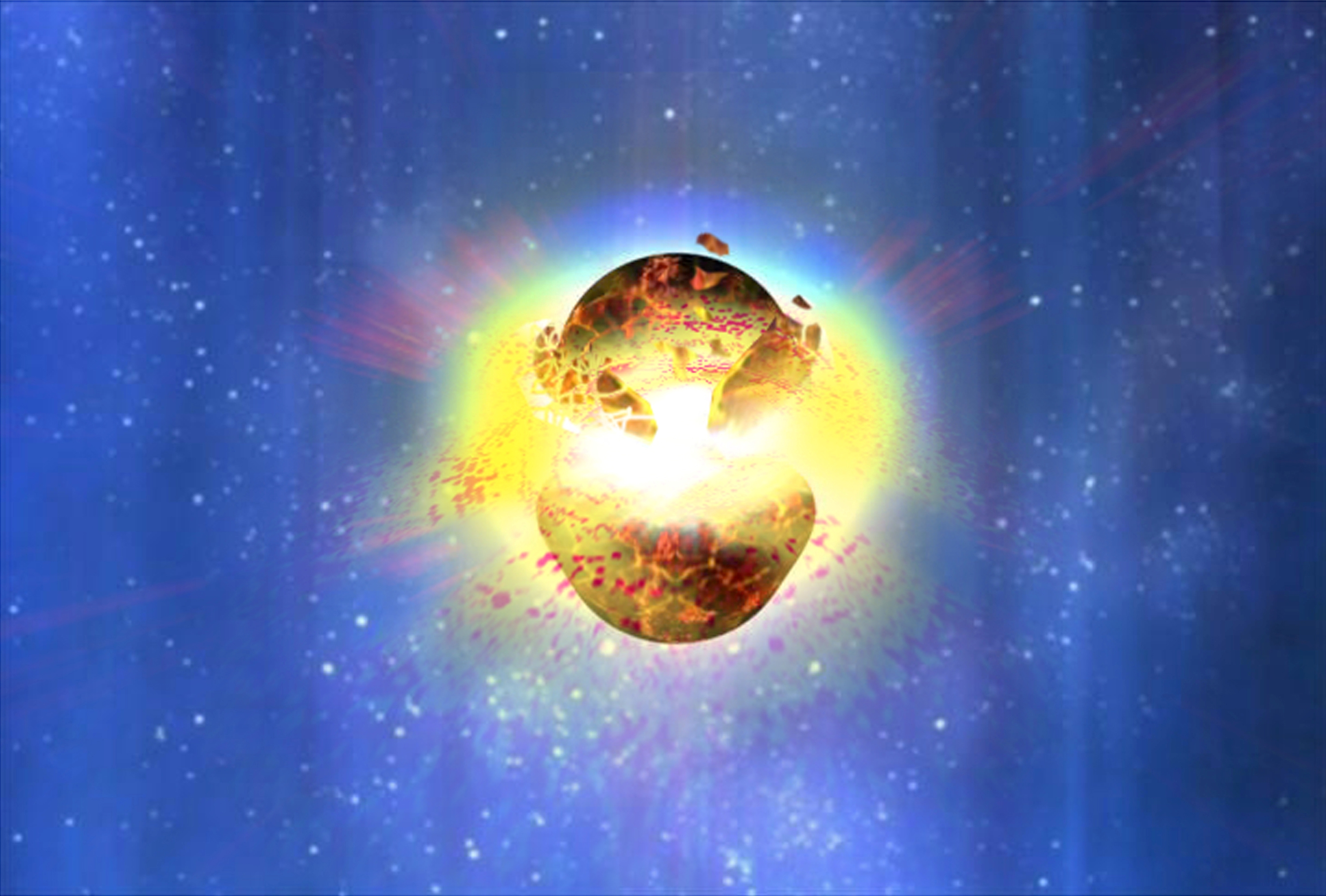

These bursts can be caused when two compact objects, such black holes or neutron stars, slam into each other and release a flood of high-energy gamma-ray radiation.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Such an interpretation, the scientists argue, fits the tree ring mystery, because a gamma-ray burst would be powerful enough to cause the uptick in carbon-14 and beryllium-10. It also fits with the fact that no rare celestial event was observed that year on Earth, at least according to records available now.

The researchers calculated that a gamma-ray burst at a distance of 3,000 and 12,000 light-years from Earth best fits the data.

"If the gamma-ray burst had been much closer to the Earth it would have caused significant harm to the biosphere," Neuhauser said in a statement. "But even thousands of light-years away, a similar event today could cause havoc with the sensitive electronic systems that advanced societies have come to depend on."

Rare chemicals

The rare forms of carbon and beryllium, which are heavier than the normal varieties of those elements, are created when radiation from space collides with nitrogen atoms in Earth's atmosphere, which then decay into carbon-14 and beryllium-10.

Both chemicals are unstable and decay on predictable time scales, allowing scientists to trace these particular tree rings back to such a specific time in the past. The fact that the jump in carbon-14 and beryllium-10 was only seen in one year's rings means whatever sparked their creation was short-lived.

"The challenge now is to establish how rare such carbon-14 spikes are, i.e., how often such radiation bursts hit the Earth," Neuhauser said. "In the last 3,000 years, the maximum age of trees alive today, only one such event appears to have taken place."

Best solution

The researchers say a gamma-ray burst explanation fits better than a solar flare, because most flares from the sun would not be powerful enough to create such a spike. Plus, they argue, a super-strong solar flare would likely have created extra-special aurora displays, which were not seen, according to historical records.

However, astrophysicists Adrian Melott of the University of Kansas and Brian Thomas of Washburn University say a flare would have to have been only about 10 or 20 times more powerful than the greatest flare on record, the so-called Carrington event of 1859. Since the records don't go back very far, such an occurrence is not out of the realm of possibility, they say.

To distinguish between the different interpretations, historians will have to look for further hints in the historical records. Neuhauser and Hambaryan also suggest looking for the object that might have resulted from the merger that caused the gamma-ray burst, which would be a 1,200-year-old black hole or neutron star that lies between 3,000 to 12,000 light-years away, but lacks the characteristic gas and dust clouds of a supernova remnant.

They report their findings Jan. 21 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.