Top 10 Questions About NASA's Columbia Shuttle Tragedy

Introduction

(Editor's note: This story was originally published on July 7, 2003.)

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — It's almost over except for the shouting.

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board's (CAIB) final report is targeted for release by the end of July and isn't expected to include many surprises that will alter the widely accepted theories about what caused the Feb. 1 tragedy.

However, what is anticipated are the specific requirements the board will levy on NASA before the agency can return the shuttle fleet to flight — some of which have already been announced — as well as the overall reaction to the report's findings from Capitol Hill and the general public.

CAIB chief Harold Gehman, a retired Navy admiral, has repeatedly said the report will attempt to put the Columbia disaster in perspective, setting the stage for renewed national debate over the true risks and benefits of human spaceflight.

At the same time, then-NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe warned agency employees the report was "going to be a nasty piece of writing" and that following the release things are "going to be really ugly."

SPACE.com presents this combination preview and summary of what we believe the CAIB will or should say, and what some of the possible consequences might be.

The information is offered in a question and answer format that is loosely organized around the draft 10-chapter report outline the CAIB released in June 2003.

FIRST STOP: Doesn't NASA Know How to Fly the Shuttle?

Doesn't NASA Know How to Fly the Shuttle?

Shuttle Columbia lifted off for the first time on April 12, 1981 on STS-1. It was the first time two astronauts flew a new U.S. spacecraft on its maiden voyage.

After only three more test flights during the next two years, NASA declared its space transportation system operational, removed the ejection seats from Columbia and began using the shuttle as a one-size-fits-all solution for the nation's commercial, military and scientific needs in space.

With each mission NASA gained more confidence in its ultimate flying machine. Crew sizes quickly grew and satellites were launched, repaired and rescued by spacewalkers buzzing around on jet backpacks.

Then the 1986 Challenger disaster popped NASA's bubble. A presidential investigation panel found fault with the shuttle's technology and NASA's decision making process. It took NASA nearly three years to fix the booster rocket problem and restructure its management.

On Sept. 29, 1988 shuttle Discovery returned America to space. It wasn't long before the shuttle program regained confidence, renewed its status as a symbol of technical superiority and resumed its role as an icon of the American spirit of exploration.

Then on Feb. 1, 2003 Columbia and its crew of seven astronauts was lost.

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board will say that despite the success the shuttle program has enjoyed, NASA has become too familiar with the program, like an old friend whose buddies have overlooked its quirks and flaws. In a word: operational. Instead, NASA must treat each shuttle mission as a test flight.

The board will point out that NASA's historic X-15 rocket plane flew 199 missions from 1959 to 1968 and every mission was considered an extremely dangerous test flight. The shuttle on the other hand has flown 113 times during a 22-year period. In effect, NASA has more experience with the vehicle that led to the shuttle than it does with the shuttle itself.

Next page: What Happened?

What Happened on Feb. 1, 2003?

On Feb. 1, 2003 shuttle Columbia's seven-member flight crew wrapped up a 16-day marathon science mission that was born out of international diplomacy, politics and a desire to keep scientists busy while awaiting final assembly of the International Space Station.

More than 80 experiments, ranging in subject matter from developing new perfumes to building stronger foundations in sandy soil, kept the crew busy working around the clock in two shifts. Problems were few.

Beginning on the second day of the flight, military radar made more than 3,000 observations of a small object drifting away from Columbia before it burned up in Earth's atmosphere.

On Feb. 1 at 8:15 a.m. EST (1315 GMT) Columbia's braking rockets were fired and the shuttle fell out of orbit heading toward a landing at Kennedy Space Center. As the shuttle passed over the United States, observers spotted glowing pieces of debris falling from Columbia.

At 8:59:32 a.m. EST (1359.32 GMT) commander Rick Husband acknowledged a call from Mission Control and was cutoff in mid-transmission, never to be heard from again. During this same period, sensors in the left wing recorded rising heat. The shuttle remained on course but was working harder than it ever had before to stay that way.

About a minute later the vehicle broke up, killing the seven astronauts and raining debris over Texas and Louisiana. Within an hour NASA was executing its disaster plan, which included forming the Columbia Accident Investigation Board. As the nation learned of the tragedy, meetings convened to determine what went wrong and the debris recovery effort began.

NASA followed its plan exactly and earned credibility in the eyes of the general public for the way it handled releasing information and helped the nation mourn the loss of seven heroes.

Ron Dittemore, the recently retired shuttle program manager, should be commended for the way he represented NASA during those first awful days.

Next page: What Broke?

What Broke on Columbia that Caused the Tragedy?

Shuttle Columbia and its crew were lost during re-entry when the incredible heat that is generated from atmospheric friction entered the interior of the left wing, causing it to melt from within until it failed and broke free. When this occurred the shuttle spun out of control and disintegrated.

It is believed the seven astronauts died instantly.

Heat protection tiles and thermal blankets cover most of the shuttle to act as its heatshield. The nose cap and leading edge of the wings are protected by panels of reinforced carbon carbon (RCC), a composite material capable of withstanding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. A small hole in the left wing's leading edge initially allowed the heat inside the wing. As the material eroded away the breach grew larger until the wing was consumed.

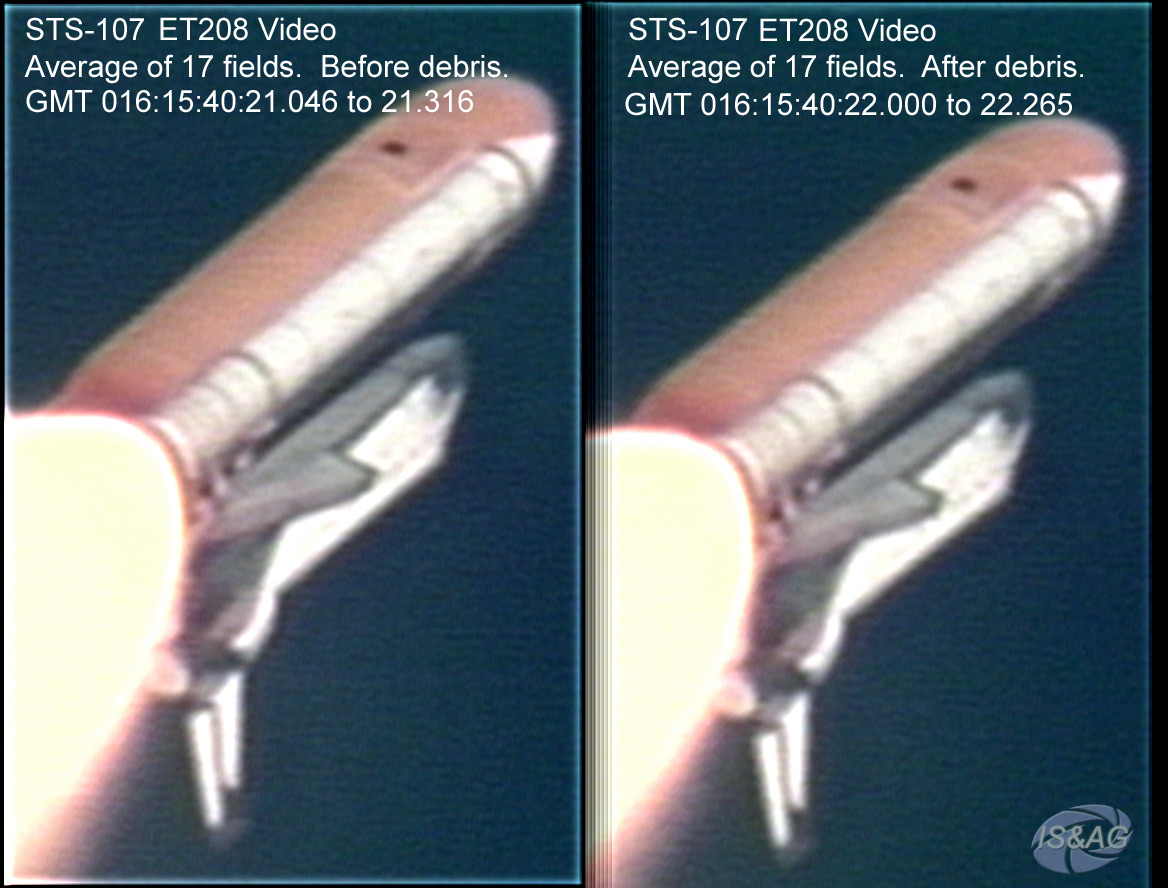

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board will say they are positive — but can't conclusively prove — that a piece of foam insulation fell from the shuttle's external tank about 82 seconds after launch and struck the left wing's leading edge, damaging a panel of the RCC material.

It's likely that the object seen via military radar floating from Columbia during the second day of the mission was a piece of the shuttle's heatshield, which either caused the breach in the left wing or contributed to making it larger.

Reconstruction of the recovered debris at the Kennedy Space Center, an analysis of data recorded during the launch and re-entry, as well as the results of tests in which foam was shot at heatshield material all independently back up the theory.

It's more than circumstantial evidence and less than proof positive. Beyond a reasonable doubt describes it best.

Next page: How Could it Happen?

How Could NASA Let This Happen?

The only part of human spaceflight that happens in a vacuum is the spaceflight itself. The rest of a mission takes place amid a dense collection of people and organizations that are susceptible to every human strength and weakness.

So when there's a failure of the magnitude of the Columbia tragedy, investigators often find there was more than a random technical failure to blame. Someone or some organization probably failed as well. People screw up.

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board is going to say just that.

Many more factors than a piece of foam hitting the wing at launch caused the disaster. Congress and the White House, previous NASA officials and administrators, outside experts and safety panels -- all tied together through the annual budget process -- all contributed to creating an environment that allowed this tragedy to happen.

More specifically, the whole way the shuttle program is organized among NASA and its contractors, which establishes the lines of authority and channels for communication, is supposed to prevent disaster. Yet seven astronauts lost their lives.

The Columbia report will offer a strong history lesson on how the agency's organization has changed through the years, especially after the Challenger disaster and through the more recent effort to turn over shuttle operations more and more to a private contractor, namely the United Space Alliance.

So here's the big question: When the dust settles will shuttle program management be centralized at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, or at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C.?

The pendulum has swung both ways during the shuttle program's history.

Which way will the CAIB say NASA should swing next?

Next page: Missed Signals

So what was NASA thinking?

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board has taken great pains to avoid falling into the trap of having 20/20 hindsight because what seems clear now wasn't before the tragedy.

The 1967 Apollo 1 fire is a great example: Pump pressurized pure oxygen into a capsule, lock three guys inside for a day and hope there are no problems with the miles of wiring.

In the case of the Columbia tragedy, no one saw the big picture. The clues were there, but no one realized there was a puzzle to solve in the first place.

First, the external tank was designed with a layer of insulation foam that isn't supposed to shed during launch. It was designed to stick to the tank, so if it's not sticking then something isn't working the way it's supposed to be.

Second, the shuttle's heatshield of tiles, RCC panels and thermal blankets were not designed to be damaged in any way for any reason. That's why the orbiter isn't allowed to fly through rain, stay outside when it hails or risk having workers drop tools on it. The tiles are especially fragile.

But for some reason, when foam fell off at launch and damaged tiles, NASA managers didn't seem alarmed. When the shuttle came back and there wasn't significant damage, managers convinced themselves there was no safety of flight issue. After 112 flights in which foam shed 70 times and tiles came back damaged every time, shuttle officials got used to it.

Some call it "gambler's dilemma." The roulette wheel had come up red 112 times in a row, so there was no reason to believe it wouldn't come up red again. Author Diane Vaughan, writing about Challenger, called it the "normalization of deviance."

We call this stupid. But then again, having covered the space program for some two decades, we never connected the dots either and we had the same information.

The board is going to tell NASA to set up a safety group that will step back and be extra sensitive to listen to what the hardware is saying when it doesn't work as designed — a group that is going to go looking for the "unknown unknowns."

Next page: Safety First

Who Is Responsible for Safety at NASA?

Everyone at NASA is responsible for safety.

While that sentiment makes a great quote or looks good as an inspirational catch phrase on an office wall poster, it's much more difficult to fully realize.

One of NASA's biggest challenges now is to ensure that everyone who is qualified to make observations and participate in making things safer knows how to offer their input — whether they are part of a particular program's normal chain of command or not.

During testimony before the Columbia board by safety officials, witnesses often confused board members with their descriptions of who they report to and where their budget comes from. As a result, the CAIB report is going to call for NASA to establish clearer lines of authority within the safety community.

To help illustrate their thinking, the board will describe how other high-risk operations — such as aboard nuclear-powered submarines — balance safety with such factors as engineering requirements, schedule and budget.

The way NASA deals with e-mails in the future also deserves some scrutiny. When an engineer asks a safety-related question and uses rather informal, but dramatic language (e.g. "If you don't fix this it's going to be a bad day!") a system should be in place to clarify intent. Is this water cooler talk between friends? Or a serious cry for help from a concerned engineer?

Meanwhile, the CAIB — but especially Congress — needs to be careful not to fall into the trap of demanding additional eyeballs and bodies for safety just for the sake of saying you've doubled the size of the organizations. In some cases the extra people will just get in the way.

If new bodies are required they should be empowered to make a difference and put a stop to things if needed. Remember, a NASA safety person isn't automatically better than a contractor safety person. It's more critical that the right number of qualified people are doing the job and keeping an eye on things in the first place.

Next page: Repair Plan

What Needs to be Fixed?

As one senior shuttle manager has explained, there will be three "buckets of work" that will come out of the Columbia board report.

The first will include all of those tasks that must be done before the shuttle can start flying again. The second will include those tasks that must be done as soon as possible, but are not a constraint to flight. The third bucket will hold those jobs that must be done when the technology can be developed and worked into the schedule.

The difficult job will be to make sure that first bucket doesn't get too full. Some lawmakers who are less willing to accept the inherent risks of spaceflight may want to load up the first bucket so full that NASA won't get another shuttle off the ground for years. That would be a tragedy as bad as Columbia and Challenger disasters combined.

Both the Columbia board and NASA managers have said they see nothing that should preclude the shuttle from safely returning to flight within the next six to nine months. We're still betting on seeing the next shuttle mission fly around Easter 2004.

We agree that the first bucket should include the jobs the board has already announced — detailed on the next page — as well as putting in place changes to the way NASA manages safety. The agency needs to assemble a team of experts who will study issues like in flight anomalies and problem reports during ground processing. Their job is to see if there is a pattern that's telling a bigger story.

NASA officials are fond of saying "We have to convince ourselves it's safe to fly." That phrase should be eliminated from the space program because its meaning can go both ways. Shuttle program officials convinced themselves it was safe to fly even though shedding foam and damaged tiles were a problem seen on dozens of previous flights.

A more specific list of fixes with detailed explanations was recently presented in Florida Today's outstanding series of reports called "Seven Fixes Needed for Return to Flight."

That list included reducing the number of safety waivers, minimizing risk from foam, improving agency communications, developing an in-flight repair plan, track safety problems better, make sure the right work force is in place, and consider different re-entry paths to avoid flying over large populations.

We agree with all of them except the final one — a debate that can be held another time.

Next page: Early Orders

What Did the CAIB Say Should be Done?

To date the CAIB has officially released four findings and recommendations. They were put out ahead of the final report because the board had already agreed on the intent and wording, and by releasing them sooner than later NASA would be able to begin work on implementing them as soon as possible.

As it turned out, the space agency was already well into planning their execution of each of these as they were announced. Here's what the board has so far said needs to get done:

• NASA must formalize a procedure with the National Imagery and Mapping Agency to obtain pictures of a space shuttle in orbit during every mission.

The idea is to use classified spy satellites to take pictures of the shuttle and see if there's any worrisome tile damage. Ideally the pictures will be taken early in the mission, in daylight, and require the shuttle to maneuver to offer its best perspective -- all of which will have an impact on mission planning. The requirement is the result of NASA not asking for such imagery during Columbia's mission.

Officials didn't ask for the pictures because they didn't think they would see anything. And they were probably right. Given the location and size of the damage to Columbia's wing leading edge it's extremely unlikely a spy satellite would have picked up anything. In fact there's some doubt even a spacewalking astronaut with his face right on the spot would have seen anything.

• NASA must inspect the RCC panels on each shuttle wing between each mission, preferably without having to remove them or destroy them in the process.

The expensive and time-consuming-to-make panels can hide flaws inside that a simple visual inspection won't reveal. Officials say this is probably one of the more technically challenging requirements the board has made so far.

• NASA must come up with procedures and equipment that will allow shuttle astronauts to inspect and repair the heat protection tiles and RCC panels without help from the ground or relying on being able to dock with the International Space Station.

While this was studied before shuttle flights began in 1981, nothing was ever certified for flight. Advances in materials and experience gained with spacewalking during the past two decades makes this a more achievable goal than first believed. It's also something NASA began working on within days of the Columbia accident and officials are confident they'll be ready with something soon.

• NASA must have at least three good cameras providing different views of a shuttle launch through solid rocket booster separation.

The ancient camera systems along Florida's Space Coast -- most of which are operated by the Air Force's 45th Space Wing -- provided the views that showed the chunk of foam striking Columbia's wing. A view -- one of three -- that would have helped engineers analyze the debris hit was not available because the camera wasn't working.

Included in the wording of the requirement is that NASA make the three camera views a criteria for launch, that the camera systems be upgraded and that the space agency consider providing new views from mobile assets such as a jet chase plane. We think that would be helpful and provide cool new views of a shuttle launch.

All four recommendations are considered "must do" before the shuttle can return to flight, but none should take long to implement. The NIMA deal is already signed, for example.

Next page: Vision of the Future

How Much Longer Should the Shuttle Fly?

We believe the shuttle should continue to be flown until it has launched every component of the space station that is already designed and built for delivery to orbit by the shuttle — however long that takes. NASA thinks it needs the shuttle through 2020.

At the same time, the nation must move forward on building a new vehicle whose sole purpose is to fly humans to and from Earth orbit, which for now seems to be going by the name of Orbital Space Plane (OSP).

The OSP doesn't have to be fancy and include all the latest bells and whistles not even invented yet. It just has to work using proven technology. And if the OSP is available before the shuttle is finished with the space station, then the shuttle should be modified to launch, cruise, dock, undock, re-enter and land by remote control.

In the meantime, the shuttle must continue to be upgraded where it can to make it safer for the astronauts, remembering that it's impossible to make every shuttle mission completely risk free.

Beginning now, all future cargo destined for the space station or anywhere else in space should be designed to fly atop the nation's expendable launch vehicles. And in order to retire the shuttle as soon as possible, a re-useable cargo carrier that can return a large amount of weight from orbit should be added to our bag of tricks.

And while we're building this wish list, add some kind of autonomous, re-useable orbital maneuvering vehicle capable of moving satellites between orbits.

If you want to talk about sending humans beyond low Earth orbit, then start designing those ships too — but don't try to make up one ship that can do all things to all people and employ the latest cutting edge technology. That's what people asked for during the 1970s and we got the space shuttle — the most marvelous, capable flying machine ever invented that didn't deliver on its promise.

Double NASA's budget for the next 10 years and we can do all of this and so much more. Unfortunately we don't think the White House nor Congress — whether led by the Republicans or the Democrats — will have the political guts to provide the leadership and money to do so.

Finally, we believe the very last shuttle mission ever flown should be on a mission to retrieve the Hubble Space Telescope from orbit and bring it back to Earth. Both belong on display at the National Air and Space Museum.

Next page: CAIB Report Card

Did the CAIB do a Good Job?

The short answer is yes.

A little longer answer is they did a great job, covered all their bases, had the right people looking at the right things and approached the whole thing from an appropriately objective point of view.

Watching all of the public hearings and participating or listening in on almost all of the press conferences, we could see how the board members were catching on to the issues and grew in their understanding of the technical and management challenges the space agency faces every day.

There were no prima donnas on this panel. When they said they were split up into working groups, they weren't kidding.

And throughout all of the proceedings, board chairman Hal Gehman kept things moving with efficiency and good humor.

There was never any doubt about the board's independence of NASA, even if it made reporting on their activities a little more difficult from time to time by not taking full advantage of NASA TV resources at the major centers.

But with callouts to the media, phone bridges to participate remotely and a willingness to hold regular news briefings, no can say fairly that the board did all of its business in secret.

Sure, they conducted more than 200 privileged interviews that may never see the light of day — a fact that bruised the egos of several lawmakers. But allowing space workers to tell their story anonymously works best in the space program. It may not be the most credible way to report a news story, but sometimes it's the only way to get the real story.

Although we haven't seen the final report yet, from what we can tell so far we believe the CAIB will produce a report that will offer the real story of what happened, explain why, and offer a framework for debating the direction NASA's space program should take in the future.

Then it will be up to all of us to ensure Rick Husband, Willie McCool, Kalpana Chawla, Laurel Clark, Mike Anderson, David Brown and Ilan Ramon did not die in vain.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jim Banke is a veteran communicator whose work spans more than 25 years as an aerospace journalist, writer, producer, consultant, analyst and project manager. His space writing career began in 1984 as a student journalist, writing for the student newspaper at Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, The Avion. His written work can be found at Florida Today and Space.com. He has also hosted live launch commentary for a local Space Coast radio station, WMMB-AM, and discussed current events in space on his one-hour radio program "Space Talk with Jim Banke" from 2009-2013.