An unusually high number of galaxies are aligned along a single plane running through the center of the giant Andromeda galaxy. Scientists don't have a theory to explain why.

Galactic cannibalism or dark matter may be responsible, researchers say.

The Andromeda galaxy is located at a distance of 2.5 million light-years away and is the nearest spiral galaxy to the Milky Way. Like our own galaxy, Andromeda is surrounded by numerous dwarf galaxy satellites. Many of these satellites are within 1.3 million light-years or less of the galaxy's main disk.

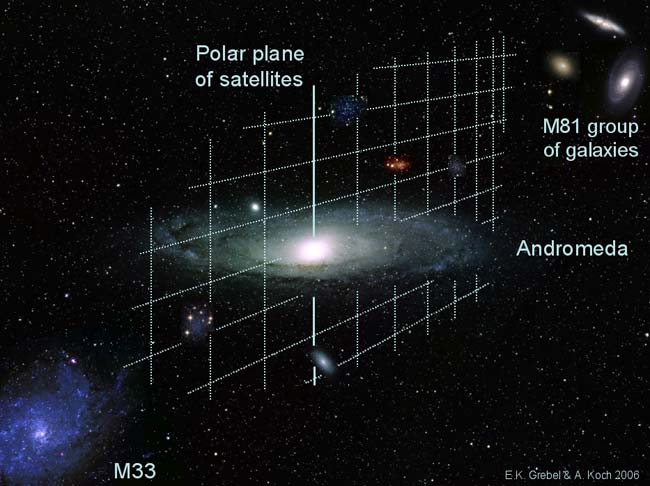

Using the Hubble Space Telescope, Eva Grebel and Andrew Koch from the University of Basel in Switzerland found that nine out of Andromeda's fourteen dwarf galaxy satellites reside in a single plane. The plane is about 52,000 light-years wide and is aligned perpendicular to Andromeda's own galactic plane, within which the galaxy's stars orbit about the center.

That nearly 80 percent of Andromeda's satellite galaxy mass is located within a single plane is highly unusual and can't be accounted for by traditional theories of galaxy formation, Grebel said.

The finding was announced recently at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

The Milky Way was found to contain two similar planes of satellite galaxies in the late 1980s, but with nothing to compare them to, astronomers couldn't tell if such planes were a general property of galaxy formation or whether they were just a statistical fluke.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"One of the open questions was always 'Do such planes of satellite galaxies exist around other galaxies?'" Grebel said. "If they do, it might indicate that it's more than just chance."

The researchers aren't sure what might be responsible for the strange alignment but they offered two possible scenarios.

Galactic Cannibalism

Perhaps long ago Andromeda swallowed a nearby orbiting galaxy but did a messy job of it; the galactic crumbs from that meal became Andromeda's satellite dwarf galaxies. Such instances of galactic cannibalism are common and are believed to play a major role in galaxy formation.

"If this scenario were correct, we would expect these satellites to maintain the original orbit from the original galaxy form which they came," Grebel explained. Early results from computer models suggest that such a scenario is physically possible.

But it might be several years before this hypothesis can be confirmed, since accurate orbital measurements for Andromeda's satellite galaxies are extremely difficult due to their distance, she added.

Dark matter stream

Another intriguing possibility is that the satellite galaxies are actually embedded in a stream of hypothetical dark matter flowing between two massive objects.

The plane containing Andromeda's satellite galaxies points toward two such objects: M33, a spiral galaxy located 0.7 million light-years away from Andromeda and M81, a cluster of about 30 galaxies that is 11 million light-years away.

It could be that the satellite galaxies are gravitationally attracted to these streams of dark matter and clumping around them, giving the appearance of being aligned along a single, wide plane.

Grebel stressed that at this point, both of these scenarios are just speculation.

"We have no proof whether any of these is actually true," she said.

It may turn out that the alignment is due to chance after all or that another explanation entirely may be responsible.

Michael Turner, a cosmologist at the University of Chicago who was not involved in the study, found the results intriguing.

"It's getting at this very simple question: how did our backyard get assembled?" Turner said.

- Small Galaxy Punches Hole In Andromeda

- Andromeda Galaxy 3 Times Bigger than Thought

- Scientists Map Dark Matter, Prove Einstein Right

- Cosmic Fossils Show Milky Way Is a Galaxy Gobbler

- Nearest Galaxy Ripped from Another, Study Suggests

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.