Columbia Disaster: What happened and what NASA learned

The space shuttle Columbia disaster changed NASA forever.

The Columbia disaster occurred On Feb. 1, 2003, when NASA’s space shuttle Columbia broke up as it returned to Earth, killing the seven astronauts on board. NASA suspended space shuttle flights for more than two years as it investigated the cause of the Columbia disaster.

An investigation board determined that a large piece of foam fell from the shuttle's external tank and breached the spacecraft wing. This problem with foam had been known for years, and NASA came under intense scrutiny in Congress and in the media for allowing the situation to continue.

The Columbia mission was the second space shuttle disaster after Challenger, which saw a catastrophic failure during its launch in 1986. The Columbia disaster directly led to the retirement of the space shuttle fleet in 2011. Now, astronauts from the US fly to the International Space Station on Russian Soyuz rockets or aboard commercial spacecraft, like the SpaceX Crew Dragon capsules which began a "space taxi" service to the ISS in 2020.

Related: Shuttle Columbia's Final Mission: Photos from STS-107

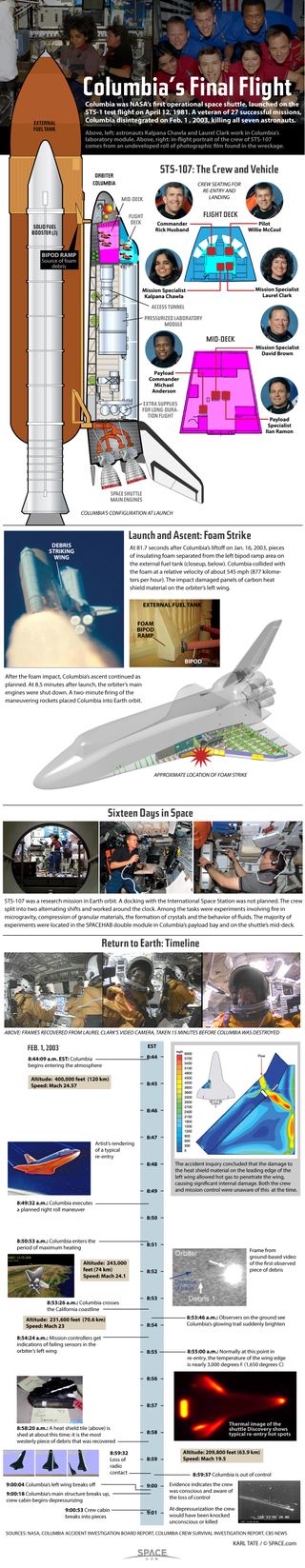

Columbia was the first space shuttle to fly in space; its first flight took place in April 1981, and it successfully completed 27 missions before the disaster. On its 28th flight, Columbia left Earth for the last time on Jan. 16, 2003. At the time, the shuttle program was focused on building the International Space Station. However, Columbia's final mission, known as STS-107, emphasized pure research.

Columbia disaster crew members

The seven-member crew — Rick Husband, commander; Michael Anderson, payload commander; David Brown, mission specialist; Kalpana Chawla, mission specialist; Laurel Clark, mission specialist; William McCool, pilot; and Ilan Ramon, payload specialist from the Israeli Space Agency — had spent 24 hours a day doing science experiments in two shifts. They performed around 80 experiments in life sciences, material sciences, fluid physics and other matters before beginning their return to Earth's surface.

What caused the space shuttle Columbia disaster?

During the crew's 16 days in space, NASA investigated a foam strike that took place during launch. About 82 seconds after Columbia left the ground, a piece of foam fell from a "bipod ramp" that was part of a structure that attached the external tank to the shuttle. Video from the launch appeared to show the foam striking Columbia's left wing. It was later found that a hole on the left wing allowed atmospheric gases to bleed into the shuttle as it went through its fiery re-entry, leading to the loss of the sensors and eventually, Columbia itself and the astronauts inside.

Several people within NASA pushed to get pictures of the breached wing in orbit. The Department of Defense was reportedly prepared to use its orbital spy cameras to get a closer look. However, NASA officials in charge declined the offer, according to the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) and "Comm Check," a 2008 book by space journalists Michael Cabbage and William Harwood, about the disaster. The landing proceeded without further inspection.

On Feb. 1, 2003, the shuttle made its usual landing approach to the Kennedy Space Center. Just before 9 a.m. EST, however, abnormal readings showed up at Mission Control. Temperature readings from sensors located on the left wing were lost. Then, tire pressure readings from the left side of the shuttle also vanished.

The Capcom, or spacecraft communicator, called up to Columbia to discuss the tire pressure readings. At 8:59:32 a.m., Husband called back from Columbia: "Roger," followed by a word that was cut off in mid-sentence.

At that point, Columbia was near Dallas, traveling 18 times the speed of sound and still 200,700 feet (61,170 meters) above the ground. Mission Control made several attempts to get in touch with the astronauts, with no success.

Twelve minutes later, when Columbia should have been making its final approach to the runway, a mission controller received a phone call. The caller said a television network was showing a video of the shuttle breaking up in the sky.

Shortly afterward, NASA declared a space shuttle 'contingency' and sent search and rescue teams to the suspected debris sites in Texas and later, Louisiana. Later that day, NASA declared the astronauts lost.

"This is indeed a tragic day for the NASA family, for the families of the astronauts who flew on STS-107, and likewise is tragic for the nation," stated NASA's administrator at the time, Sean O'Keefe.

Searching for Columbia debris

The search for debris took weeks, as it was shed over a zone of some 2,000 square miles (5,180 square kilometers) in east Texas alone. NASA eventually recovered 84,000 pieces, representing nearly 40 percent of Columbia by weight. Among the recovered material were crew remains, which were identified with DNA.

Much later, in 2008, NASA released a crew survival report detailing the Columbia crew's last few minutes. The astronauts probably survived the initial breakup of Columbia, but lost consciousness in seconds after the cabin lost pressure. The crew died as the shuttle disintegrated.

Report calls for more funding, emphasis on safety

In the weeks after the disaster, a dozen officials began sifting through the Columbia disaster, led by Harold W. Gehman Jr., former commander-in-chief of the U.S. Joint Forces Command. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board, or CAIB, as it was later known, later released a multi-volume report on how the shuttle was destroyed, and what led to it.

Besides the physical cause — the foam — CAIB produced a damning assessment of the culture at NASA that had led to the foam problem and other safety issues being minimized over the years.

"Cultural traits and organizational practices detrimental to safety were allowed to develop," the board wrote, citing "reliance on past success as a substitute for sound engineering practices" and "organizational barriers that prevented effective communication of critical safety information" among the problems found.

CAIB recommended NASA ruthlessly seek and eliminate safety problems, such as the foam, to ensure astronaut safety in future missions. It also called for more predictable funding and political support for the agency, and added that the shuttle must be replaced with a new transportation system.

"The shuttle is now an aging system but still developmental in character. It is in the nation's interest to replace the shuttle as soon as possible," the report stated.

Returning to flight and retiring the space shuttle program

The shuttle's external tank was redesigned, and other safety measures were implemented. In July 2005, STS-114 lifted off and tested a suite of new procedures, including one where astronauts used cameras and a robotic arm to scan the shuttle's belly for broken tiles. NASA also had more camera views of the shuttle during liftoff to better monitor foam shedding.

Due to more foam loss than expected, the next shuttle flight did not take place until July 2006. After STS-121's safe conclusion, NASA deemed the program ready to move forward and shuttles resumed flying several times a year.

"We're still going to watch and we're still going to pay attention," STS-121 commander Steve Lindsey said at the time. "We're never ever going to let our guard down."

The shuttle fleet was maintained long enough to complete the construction of the International Space Station, with most missions solely focused on finishing the building work; the ISS was also viewed as a safe haven for astronauts to shelter in case of another foam malfunction during launch. A notable exception to the ISS shuttle missions was STS-125, a successful 2009 flight to service the Hubble Space Telescope. NASA administrator Sean O'Keefe initially canceled this mission in 2004 out of concern from the recommendations of the CAIB, but the mission was reinstated by new administrator Michael Griffin in 2006; he said the improvements to shuttle safety would allow the astronauts to do the work safely.

The space shuttle program was retired in July 2011 after 135 missions, including the catastrophic failures of Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003 which killed a total of 14 astronauts. NASA developed a commercial crew program to eventually replace shuttle flights to the space station and brokered an agreement with the Russians to use Soyuz spacecraft to ferry American astronauts to orbit.

Columbia's legacy

Some of the experiments on Columbia survived, including a live group of roundworms, known as Caenorhabditis elegans. Investigators were surprised that the worms — about 1 millimeter in length — survived the re-entry with only some heat damage. Some of the descendants of these roundworms flew into space in May 2011 aboard the space shuttle Endeavour, shortly before the shuttle program was retired.

Columbia's loss — as well as the loss of several other space-bound crews — receives a public tribute every year at NASA's Day of Remembrance. That date is marked in late January or early February because, coincidentally, the Apollo 1, Challenger and Columbia crews were all lost in that calendar week.

In 2015, the Kennedy Space Center Visitor's Center opened the first NASA exhibit to display debris from both the Challenger and Columbia missions. Called "Forever Remembered," the permanent exhibit shows part of Challenger's fuselage, and window frames from Columbia. Personal artifacts from each of the 14 astronauts are also on display. The exhibit was created in collaboration with the families of the lost astronauts.

The crew has received several tributes to their memory over the years. On Mars, the rover Spirit's landing site was ceremonially named Columbia Memorial Station. Also, seven asteroids orbiting the sun between Mars and Jupiter now bear the crew's names.

Additional resources

Read more about how the Columbia tragedy began the age of private space travel with this article by Tim Fernholz. Remember the Columbia STS-107 mission with these resources from NASA. Explore how space shuttle Discovery launched America back into space after the shuttle disasters, with this Smithsonian Magazine feature by David Kindy.

Bibliography

Cabbage, M., & Harwood, W. (2004). Comm check: The final flight of Shuttle Columbia. Free Press.

NASA. NASA Day of remembrance. NASA. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.nasa.gov/specials/dor2023/

NASA. Remembering Columbia STS-107 Mission. NASA. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://history.nasa.gov/columbia/index.html

NASA. Space shuttle Columbia. NASA. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/shuttleoperations/orbiters/orbiterscol.html

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.