Moon's Craters at Their Best in Night Sky

A lot of people lose track of the moon around this time of the lunar month. The full moon was shining bright just after sunset on Saturday (Jan. 26), but now the moon is nowhere to be seen in the early evening.

The moon is still there of course, but it has moved on in its orbit into the morning sky. It rises around 9 p.m. (your local time) and shines the rest of the night. Each night it rises about 50 minutes later because of its orbital motion around the Earth. At sunrise it is in the south, and that is probably the best time to observe it.

The moon looks strangely different in a telescope around last quarter. That's because the familiar features are being lit from the other side, by the setting sun instead of the rising sun.

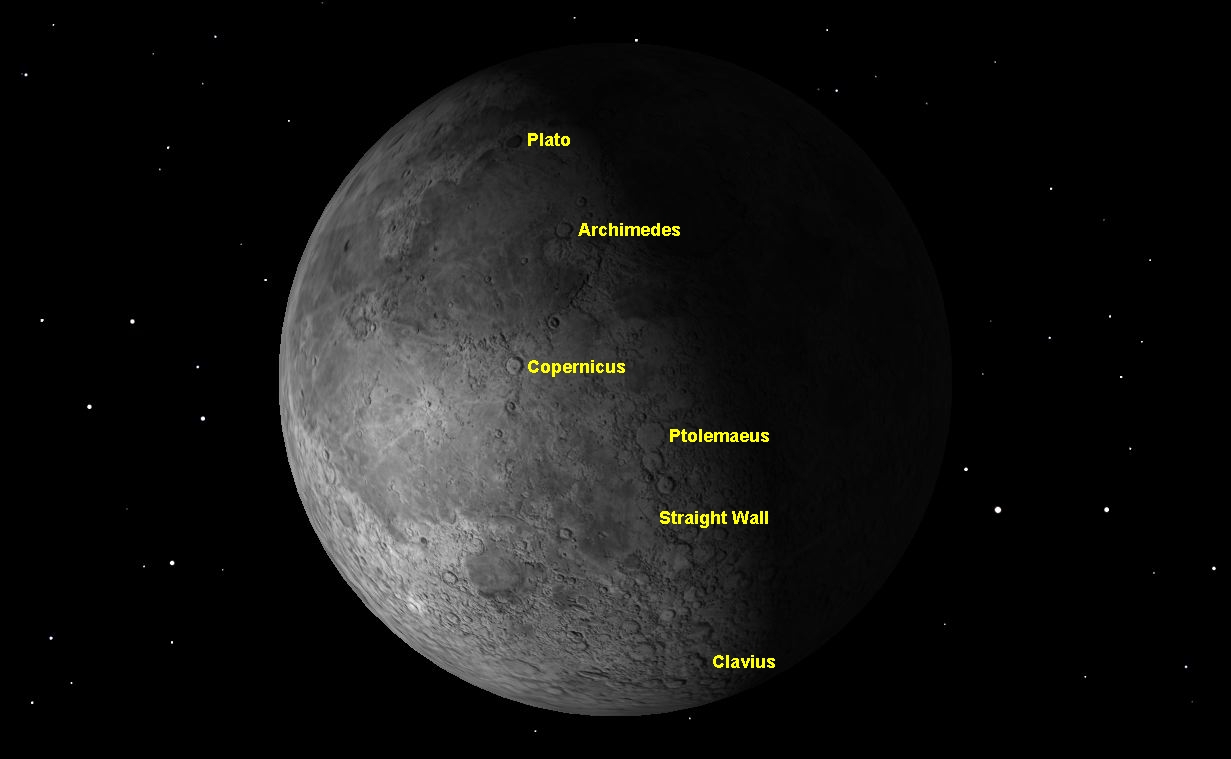

If you look at the terminator, the dividing line between light and shadow, you'll see the gigantic walled plain Ptolemaeus near the center of the moon, with its companions Alphonsus and Arzachel immediately to its south. [Amazing Moon Photos by NASA Probe]

Learning the geography of the moon has double value. Not only do you learn the names of features on another object in space, but you also learn about the history of science, because the moon’s craters are named for the famous scientists of history. It can also teach you a bit about the politics of the 17th century Roman Catholic Church.

These names were originally assigned by 17th century Jesuit astronomer Giambattista Riccioli. You can see where his political alliances lay by the fact that he gave the name "Galilaei" to a rather inconspicuous crater on the western limb of the moon.

Ptolemaeus is a crater 95 miles (153 kilometers) across, and is named after the greatest astronomer of antiquity, Claudius Ptolemaeus. He lived during the second century A.D., and his book, the "Almagest," summarized all the knowledge of astronomy obtained by the ancient Greeks.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ptolemaeus still ranked high in the eyes of the Church. Even so, Riccioli gave equal prominence to Ptolemaeus' 16th century Polish rival, Nicolas Copernicus, placing his name on one of the most beautiful craters on the moon, 58 miles (93 km) in diameter, with a central peak and terraced walls. Look particularly at the plain to the east of Copernicus, which is littered with tiny craterlets.

The perfect oval Plato crater marks the lunar Alps in the north. Named after the great 4th century Greek philosopher Plato, it is 63 miles (101 km) in diameter. Look for the Alpine Valley to the east of Plato; large telescopes will show a narrow rille meandering down its middle.

Near the South Pole is Clavius, one of the largest craters on the moon, 140 miles (225 km) in diameter. How many craters and craterlets can you count inside it? This crater was named for Christopher Clavius, the 16th century German Jesuit astronomer and mathematician who designed the Gregorian calendar, which most of the world uses today.

One feature which is strikingly different at last quarter is the Straight Wall or Rupus Rectis. This impressive cliff is 68 miles (110 km) long and up to 980 feet (300 meters) high. It casts a shadow at first quarter, making a dark line, but at last quarter its face is lit by the setting sun and appears instead as a bright white line.

If you can manage to observe the moon several mornings in a row, you can watch as the sunset shadow moves across its face, until nothing remains but a narrow crescent.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing photo of the moon or any other night sky object, that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.