Scientists Offer Wary Support for NASA's New Mars Rover

Scientists cheered NASA's decision to send a new rover to Mars in 2020, but stressed that the mission should pave the way to return Martian rocks to Earth — a major goal of the planetary science community.

In a set of statements released Jan. 28 and Jan. 30, two large and well-respected groups of scientists — the Planetary Society and the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS), respectively — shared their views on the plan to send another robotic explorer to the Red Planet in seven years.

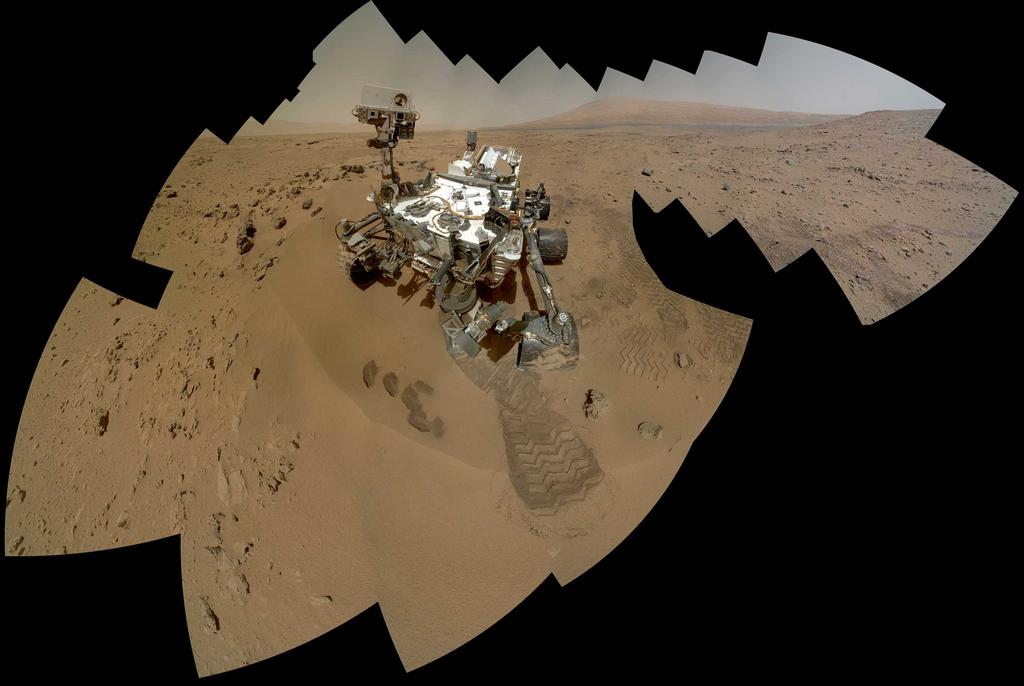

The new Mars rover mission was announced Dec. 4 by John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for science, at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. The new rover will share some design features with NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars in August to begin at least a two-year mission.

"We welcome the recent announcement that NASA will return to Mars in 2020 with a new rover derived from the MSL Curiosity design," the Planetary Society statement read. "Continued exploration of Mars is crucial to the scientific community and important for building upon our decades-long investment in engineering and technology development. However, we strongly believe that the mission should have the capability to collect and store Martian rock samples as recommended by the National Research Council's Planetary Science Decadal Survey." [Video: NASA to Launch Mars Rover in 2020]

The Decadal Survey is a report undertaken every 10 years by an independent group of scientists to determine the highest priorities for the field of planetary science (other fields, such as astronomy and astrophysics, have their own surveys). This report is generally well-respected and highly influential in allocating the limited funding within NASA's science budget.

"We strongly believe that the mission should carry a payload consistent with the recommendations given in the National Research Council’s decadal survey for planetary science, Vision and Voyages," the DPS statement read. "It is of the utmost importance that NASA and Congress follow the recommendations laid forth in the Decadal Survey in order to maximize science return and support a balanced and affordable approach to exploration in our solar system."

NASA has released scant details on the new rover plan, and it's unclear yet whether the robot will be able to collect Martian rock samples intended to be brought back to Earth. Most plans for returning Mars samples are multi-phase, with an initial mission to collect, or cache, the rocks, and later missions to rendezvous with the collector and return the samples to Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The question of caching is going to be a trade-off case," Grunsfeld said when he announced the rover. "The science definition team is going to have to weigh, what science do we want to get done? How much mass and power do we have available? What can we get to the surface, and where do we want to go?"

Both statements also pushed against budget cuts to NASA's planetary science division suggested by the Obama administration's February 2012 budget proposal. If implemented, those cuts could force NASA to retire early some of its current solar system probes, such as the Cassini Saturn orbiter and the Messenger Mercury probe, and delay future missions.

"We find the shift in budgetary priority deeply troubling," the Planetary Society scientists wrote. "Namely, it represents a step backwards from our nation's long commitment to exploration and the pursuit of answers to the big questions of 'where do we come from?' and 'are we alone?'"

The proposed budget cuts would also exclude the possibility of a mission to Jupiter's moon Europa, "long considered one of the most compelling and scientifically rich destinations in the solar system," the DPS statement read.

While many scientists agree that Mars is a valuable destination, some wish the Red Planet didn't hog all the glory — and the budget.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.