Alien Moons May Be Easier to Photograph Than Planets

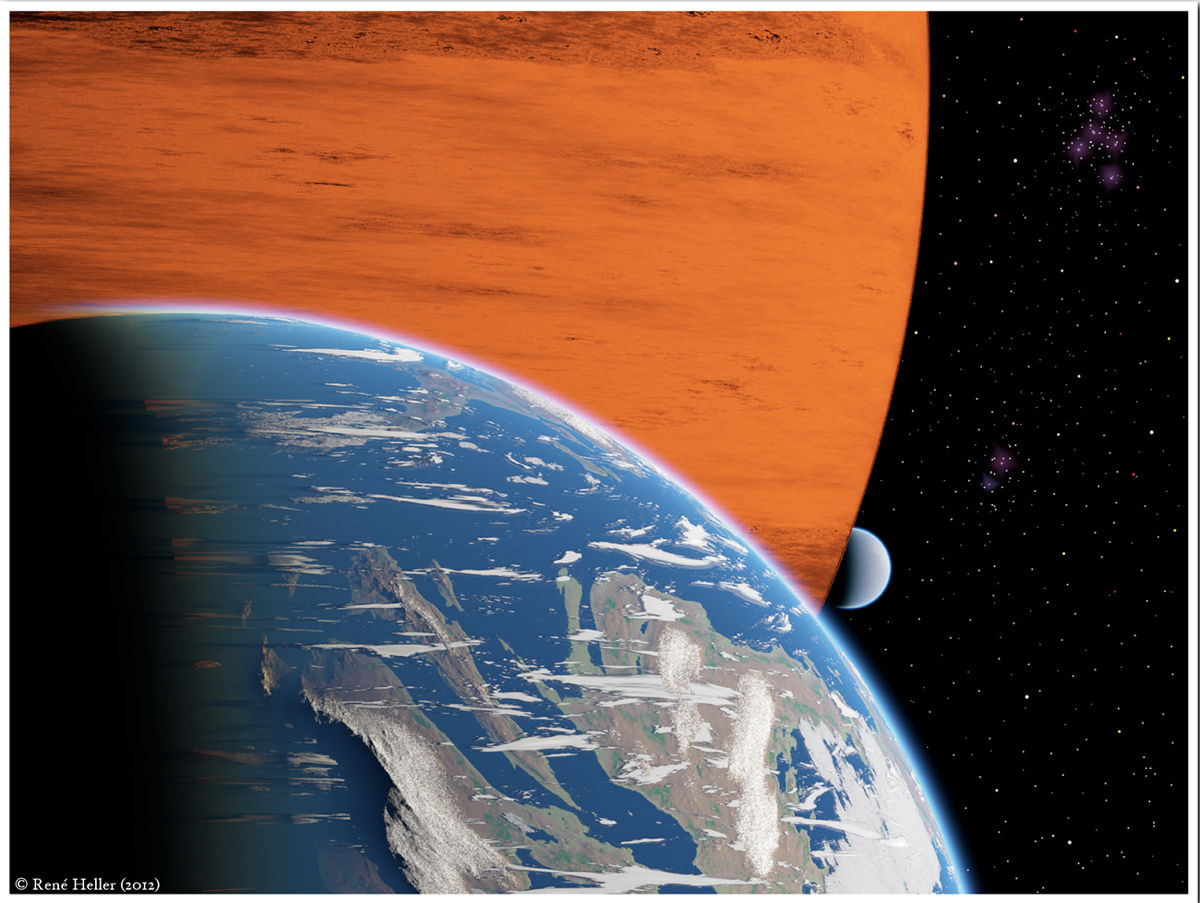

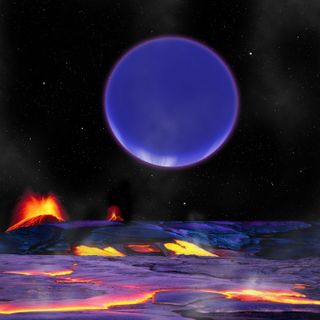

Scientists looking for habitable worlds to photograph could have better luck searching for moons than for alien planets, scientists say. A moon heated by the pull of its parent planet could be visible even when the planet is hidden from view.

Powered by gravitational tugging from a planet, these exomoons would remain bright throughout their lifetimes, not just in their youth. This means stars of various ages could be hosting planets with photogenic moons.

"Unlike traditional direct imaging, there's no star that would be a bad candidate," researcher Mary Anne Peters told SPACE.com.

Kneading alien moons

As a moon travels around its planet, the larger body tries to circularize the orbit of the smaller. But if the planet hosts more than one moon, a power struggle may ensue as the smaller bodies tug at one another. The resulting heat radiates from the moon, making it bright enough to show up in a visual image. [9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

Planets emit heat for only a short time after their formation, limiting how long they can be directly imaged. But tidally heated moons would continue to give off heat throughout their lifetimes.

How much heating a moon undergoes would depend on its location. A tighter orbit results in stronger gravitational tugs and a brighter image. But too close would be fatal.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If it gets too close, it would be torn into a ring, such as the one around Saturn," Peters said.

On the other hand, too far away would leave the moon too cool and dim to be imaged.

Just how common are such tidally heated moons? Of the 146 moons in the Earth's solar system, four are tidally locked.

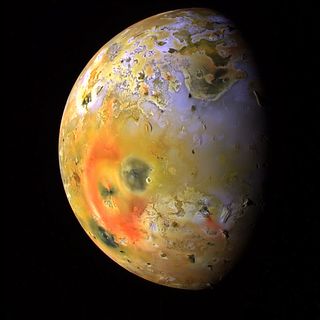

Io, Europa, and Ganymede orbit Jupiter. Their tugs on one another counteract the attempts of the gas giant to circularize their orbit. All three experience some form of tidal heating, with the closest, Io, feeling the strongest effects.

"Jupiter basically kneads Io and heats the interior by deforming it," Phillips said.

This excess energy radiates from Io, making it brighter. Saturn's moon Enceladus also experiences similar pressure as it interacts with the planet and other moons.

No such moons have been discovered outside the solar system, though Kepler, the space observatory orbiting the sun, should be sensitive enough to spot exomoons.

"There has to be at least two moons there, or the tidal heating will go away on very short times, so it only lasts a very small fraction of the lifetime of that system," Peters said.

In most cases, only the closest moons would be hot and bright enough to be imaged.

But they also would have to be big enough. Io, for example, is less than a third as wide as Earth ― too small to image from afar. If it were Earth-size, it would be bright enough to detect with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, according to Peters.

Imaging hot moons doesn't depend on a new space telescope, however.

"As far as current instrumentation, I think Spitzer would have the best chance of seeing these things," Peters said. Kepler should also be able to register a distant moon. But she emphasized that the James Webb telescope would be the best possible tool.

The research was presented at the 221st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Long Beach, California last month.

The new habitable zone

Warmed by their planet rather than their star, tidally heated moons could also shift the definition of the habitable zone, the region where liquid water could exist on a body, making it ideal for the generation of life. For water to exist, the planet — or moon — must be not too hot and not too cold. Traditionally, the region is defined by the distance from the star, but a tidally heated planet doesn’t rely on its sun.

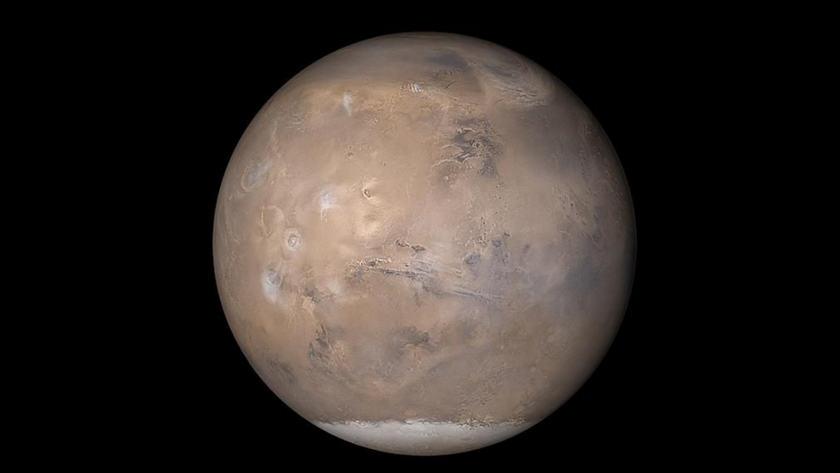

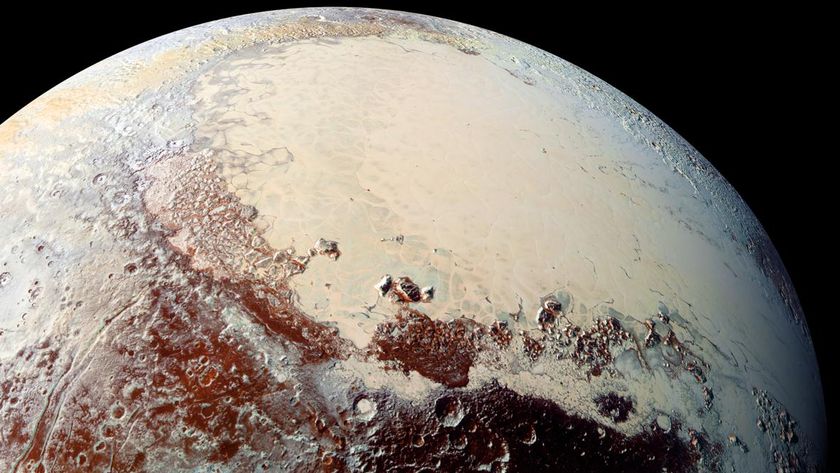

"You could have this [heating] occur at any distance, the distance of Mars or the distance of Pluto," Peters said.

When it comes to imaging, the long range is a plus. A planet in its sun's habitable zone can find itself drowned out by the light from its star. But a distantly orbiting exomoon wouldn't have that complication.

Like Io and Enceladus, tidally heated exomoons would be more likely to be volcanically active, Peters said. Such volcanism could aid in the creation of an atmosphere on the moon, another helpful ingredient when it comes to the evolution of life.

Io has a very thin atmosphere, but Peters explained that has more to do with its small size. Io lacks the gravity to hold onto a significant atmosphere. But things could be different with a larger moon.

"There's no reason why these tidally heated objects could not be habitable," Peters said.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd

Most Popular