Balloon-Borne Telescope Seeks Out Elusive Big Bang Signal

A balloon-borne telescope soared over Antarctica recently in an ambitious mission to spot a never-before-seen signal in the leftover light from the Big Bang.

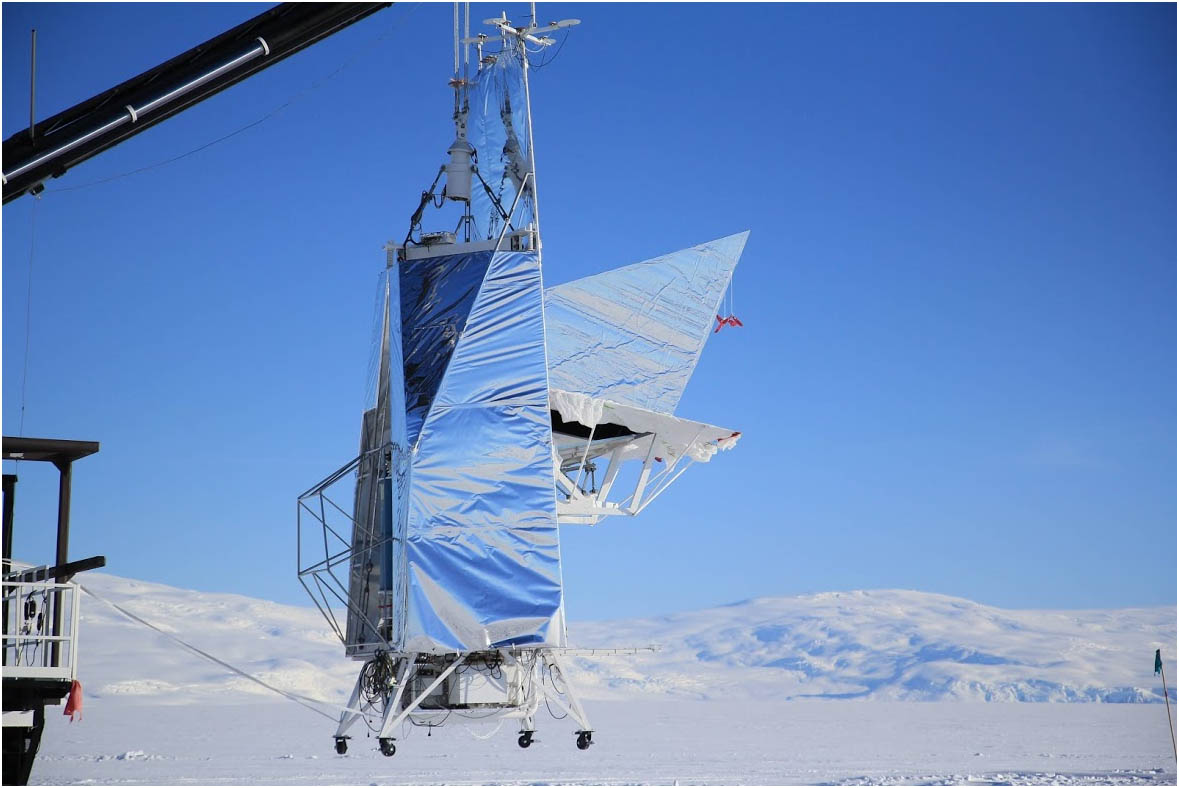

The E and B Experiment (EBEX) is a telescope that observed space from the upper atmosphere, flying on a giant balloon launched from near the South Pole on Dec. 28. The telescope returned to Earth after a weeks-long flight, but it will take scientists about a year to know whether the mission found what it was searching for.

EBEX observed the heavens in microwave light to study what's called the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is light that's been traveling through space since shortly after the dawn of the universe roughly 13.7 billion years ago.

Just after the Big Bang thought to have sparked the universe, space was hot and dense, and expanded incredibly rapidly. For its first 380,000 years, the universe was too hot for light to travel freely, as photons would continually bounce off the electrons and protons making up the thick plasma that permeated space. [See Balloon Launch to Seek Big Bang's Light (Video)]

Eventually, the universe cooled down enough for atoms to form, and for light to travel freely. The photons from that epoch have been journeying through space ever since, and make up the CMB that telescopes can detect now.

This CMB has been widely studied by observatories, including the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), which measures this radiation across the entire sky. But EBEX is meant to hone in on one specific feature of the CMB light that's been predicted, but never seen — a signature called B-type polarization, thought to have been produced by the gravity waves created by the universe's extremely rapid infant expansion, which happened even before the CMB light was released.

"We're looking for signatures from when the universe was much, much less than 1 second old," said astrophysicist Amber Miller, who leads the Columbia University team working on EBEX. "WMAP is making a baby picture of the universe. What we're trying to do is go even further back, to see not even a baby picture of the universe, but the egg of the universe."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

B-type polarization is an orientation of light waves predicted to be present in the CMB by inflation theory, which suggests the early universe expanded faster than the speed of light for a short period. To detect this signature, EBEX is equipped with a very sensitive instrument called a polarimeter that measures not just the intensity of light, but its polarization.

"Each round of new [CMB] experiments does a little bit better than the last one," Miller told SPACE.com. "No one has yet been able to get to the sensitivity needed to actually see these signatures. We might, or we might not."

Either way, EBEX should tell scientists something useful about the universe.

"If you do a good experiment and find out the signature isn't there, it means the simplest, most appealing models of how the universe was formed don't work," Miller said. "If those are wrong then we need something more exotic."

EBEX is a collaboration between scientists from 17 different institutions around the world. It was one of three balloon-borne experiments launched from Antarctica this past winter, along with the BLAST observatory, which studied stellar nurseries in the Milky Way, and the Super-TIGER experiment, which detects cosmic ray particles from space.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.