Billions of Earth-like alien planets likely reside in our Milky Way galaxy, and the nearest such world may be just a stone's throw away in the cosmic scheme of things, a new study reports.

Astronomers have calculated that 6 percent of the galaxy's 75 billion or so red dwarfs — stars smaller and dimmer than the Earth's own sun — probably host habitable, roughly Earth-size planets. That works out to at least 4.5 billion such "alien Earths," the closest of which might be found a mere dozen light-years away, researchers said.

"We thought we would have to search vast distances to find an Earth-like planet," study lead author Courtney Dressing, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), said in a statement. "Now we realize another Earth is probably in our own backyard, waiting to be spotted."

Kepler's keen eye

Dressing and her team analyzed data gathered by NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope, which is staring continuously at more than 150,000 target stars. Kepler spots alien planets by flagging the tiny brightness dips caused when the planets transit, or cross the face of, their stars from the instrument's perspective. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

Kepler has detected 2,740 exoplanet candidates since its March 2009 launch. Follow-up observations have confirmed only 105 of these possibilities to date, but mission scientists estimate that more than 90 percent will end up being the real deal.

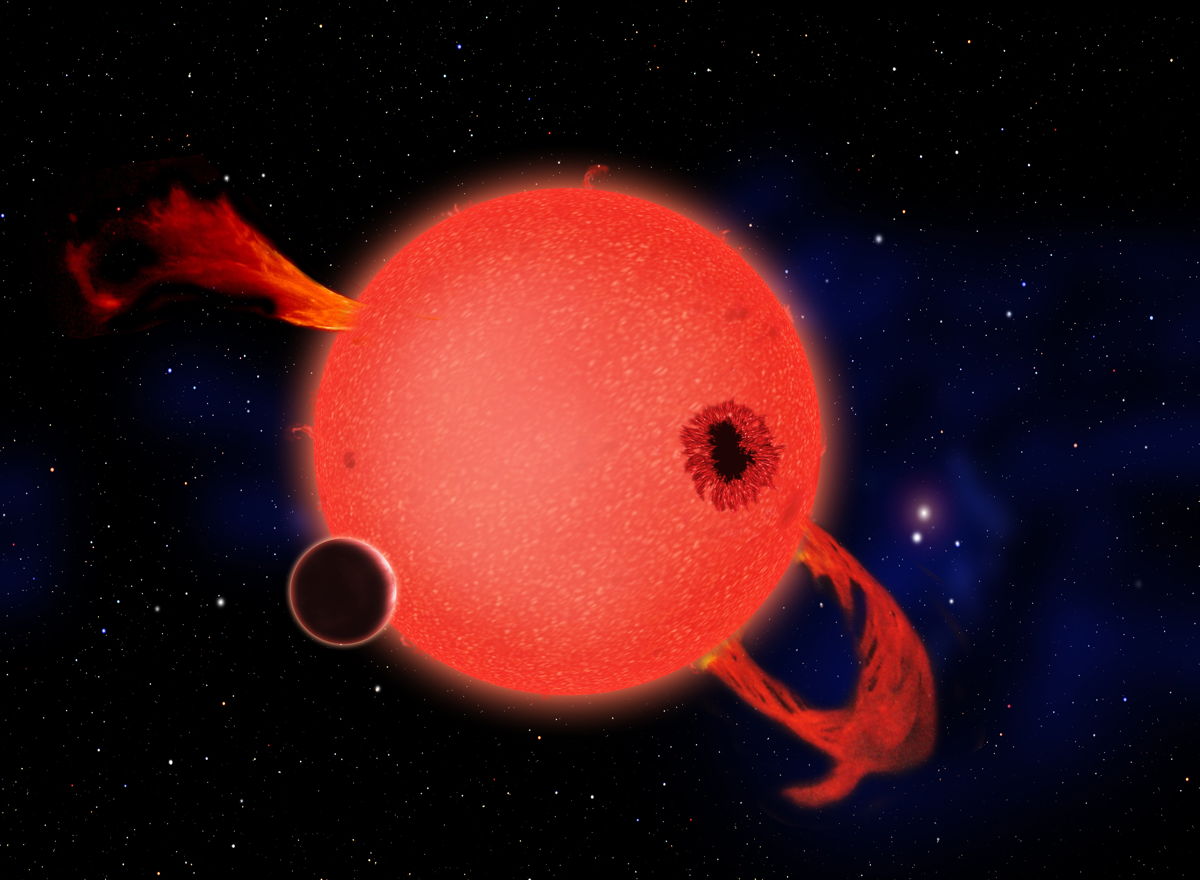

In the new study, Dressing and her colleagues re-analyzed the red dwarfs in Kepler's field of view and found that nearly all are smaller and cooler than previously thought.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This new information bears strongly on the search for Earth-like alien planets, since roughly 75 percent of the galaxy's 100 billion or so stars are red dwarfs.

Further, scientists determine the sizes of transiting exoplanets by comparison to their parent stars, based on how much of the stars' disks the planets blot out when transitting. So a reduction in a star's calculated size brings a planet's size down, too — in some cases, perhaps into the realm of rocky worlds with a solid, potentially life-supporting surface.

And the size and location of a star's "habitable zone," the range of distances that could support the existence of liquid water on a planet's surface, are strongly tied to stellar brightness and temperature.

Re-analzying the data

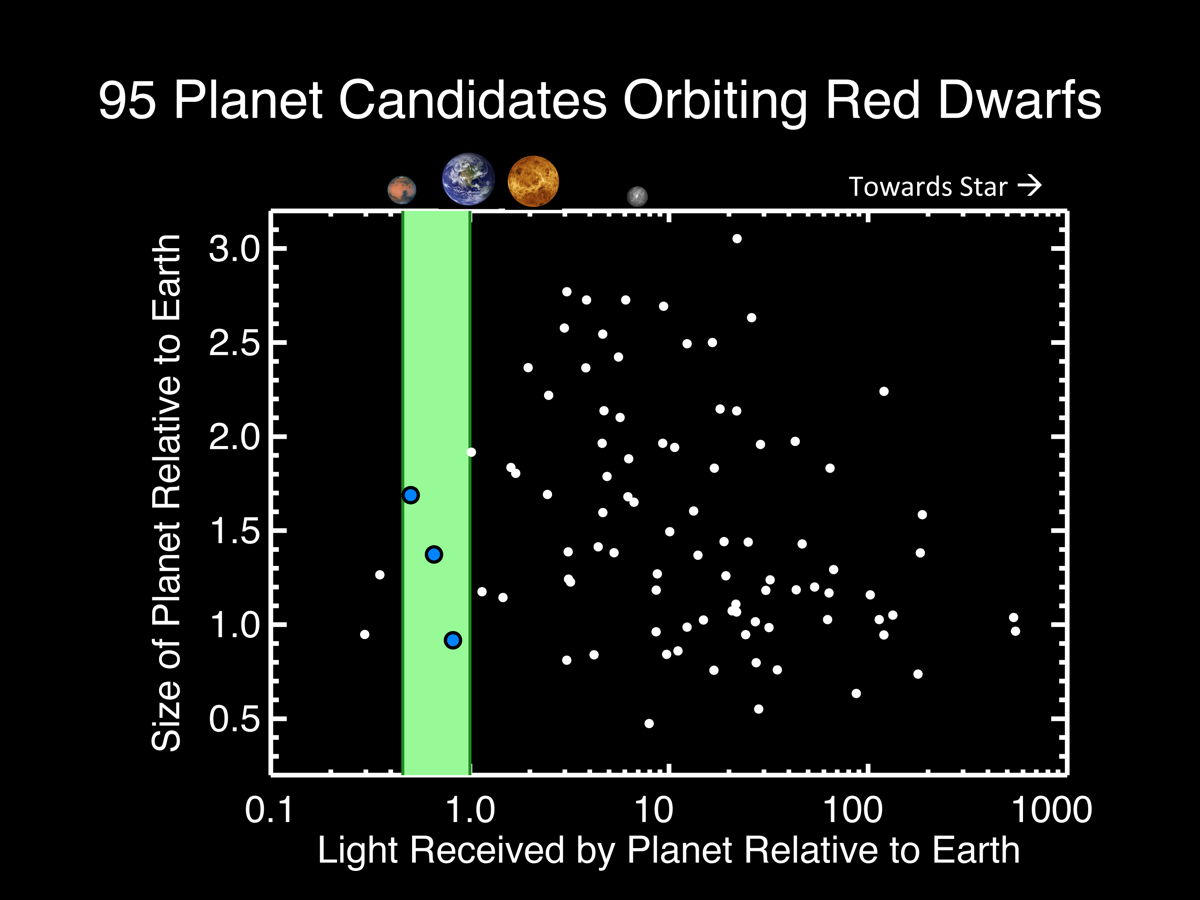

The researchers determined that 95 Kepler exoplanet candidates orbit red dwarfs. Using this information and their newly calculated stellar (and planetary) profiles, the team calculated that about 60 percent of red dwarfs likely host worlds smaller than Neptune.

Dressing and her colleagues then determined that Kepler has spotted three roughly Earth-size exoplanet candidates in the habitable zones of their parent red dwarfs.

One of these worlds is Kepler Object of Interest (KOI) 1422.02. This candidate's newly calculated size is 90 percent that of Earth, and it circles its star every 20 days. If the planet (and these characteristics) are confirmed, KOI 1422.02 may be the first "alien Earth" ever discovered.

The other two candidates are KOI 2626.01, another potential Earth twin that's 1.4 times bigger than Earth and has a 38-day orbit; and KOI 854.01, a world 1.7 times the size of Earth with a 56-day orbit.

All three candidates are located between 300 and 600 light-years from Earth and circle stars with surface temperatures between 5,700 and 5,900 degrees Fahrenheit (3,150 and 3,260 degrees Celsius), researchers said. (For comparison, the Earth's sun has a surface temperature of about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, or 5,540 degrees Celsius.)

Billions of Earth-like planets

The team further determined that about 6 percent of the Milky Way's red dwarfs should harbor roughly Earth-size planets in their habitable zones, meaning that at least 4.5 billion such worlds may be scattered throughout our galaxy.

"We now know the rate of occurrence of habitable planets around the most common stars in our galaxy," co-author David Charbonneau, also of CfA, said in a statement. "That rate implies that it will be significantly easier to search for life beyond the solar system than we previously thought." [9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

That search may bear fruit right in Earth's backyard, researchers said.

"According to our analysis, the closest Earth-like planet is likely within 13 light-years, which is right next door in terms of astronomical distances," Dressing told SPACE.com via email.

"The knowledge that another an Earth-like planet might be so close is incredibly exciting and bodes well for the next generation of missions designed to detect nearby Earth-like planets," she added. "Once we find nearby Earth-like planets, astronomers are eager to study them in detail with the James Webb Space Telescope and proposed extremely large ground-based telescopes like the Giant Magellan Telescope."

Red dwarfs are also longer-lived than stars like the sun, suggesting that some planets in red dwarf habitable zones may harbor life that's been around a lot longer than that on Earth, which first took root about 3.8 billion years ago.

"We might find an Earth that’s 10 billion years old," Charbonneau said.

The nearest red dwarf is Proxima Centauri, part of the three-star Alpha Centauri system that's just 4.3 light-years or so from Earth. Late last year, astronomers announced the discovery of an Earth-size planet orbiting the system's Alpha Centauri B, but it's far too hot to host life as we know it.

Scientists have also detected five planetary candidates circling the star Tau Ceti, which lies 11.9 light-years away. Two of these potential planets may reside in the habitable zone, but they are at least 4.3 and 6.6 times as massive as Earth, scientists say.

The new study will be published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.