NASA Asteroid-Sampling Mission to Help Gauge Impact Threat

The extremely close flyby of Earth of a 150-foot asteroid on Friday (Feb. 15) has cast a spotlight on the danger of asteroid impacts to our planet, a threat that an upcoming NASA mission aims to investigate.

This week's asteroid close encounter will occur on Friday at 2:24 p.m. EST (1924 GMT), when the asteroid 2012 DA14 has a close encounter with Earth. The asteroid will NOT hit the Earth, but it will fly within 17,200 miles (27,700 kilometers) closer than the ring of communications and navigation satellites high above the planet.

NASA and scientists around the world will track asteroid 2012 DA14 closely with radar and other instruments to learn more about its composition, spin and other details. But to truly understand asteroids enough to develop effective countermeasures to avoid future impacts, NASA needs actual pieces of the space rocks, and that's where NASA's new OSIRIS-REx mission comes in.

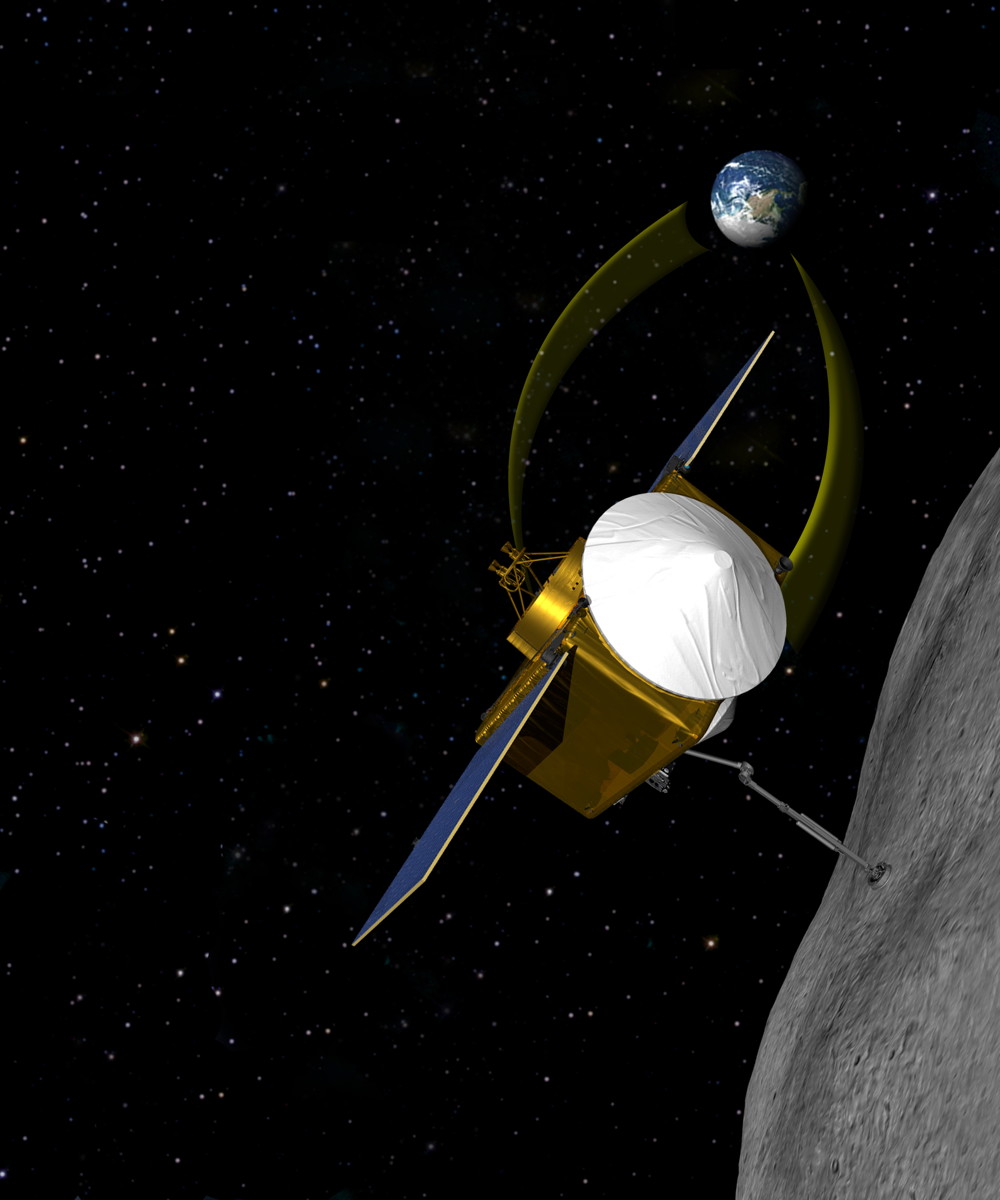

Set to launch in 2016, OSIRIS-REx is an unmanned mission to collect samples of the potentially dangerous near-Earth asteroid 1999 RQ36, which is nearly 1,500 feet (457 meters) wide, and return them to Earth. Not only will this effort collect samples of the space rock, but it will also gather the best measurements to date of the small forces that act on asteroids and make them tricky to track.

There are more than 1,300 space rocks that NASA classifies as "potentially hazardous asteroids." These objects measure at least 150 yards (about 140 meters) across and have orbital paths that bring them close to Earth's orbit. [Can Killer Asteroids Be Steered Away? (Video)]

"Asteroids move at an average of 12 to 15 kilometers per second (about 27,000 to 33,000 miles per hour) relative to Earth, so fast that they carry enormous energy by virtue of their velocity," OSIRIS-REx mission deputy principal investigator Edward Beshore of the University of Arizona, Tucson, said in a statement. "Anything over a few hundred yards across that appears to be on a collision course with Earth is very worrisome."

While it’s thought that chances of an impact are slim, it is difficult to predict the orbits of these objects with a comforting amount of certainty. That is in part because Earth's gravitational pull changes an asteroid's path as it approaches the planet. There are also other small forces continuously altering its orbit, scientists say.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The most significant of these smaller forces is the Yarkovsky effect — a minute push on an asteroid that happens when it is warmed up by the sun and then later re-radiates this heat in a different direction as infrared radiation," Beshore said. OSIRIS-REx stands for Origins-Spectral Interpretation-Resource Identification-Security-Regolith Explorer.

The asteroid 1999 RQ36, or RQ36 for short, has one of the highest known probabilities of slamming into Earth, a 1-in-2,400 chance of impact late in the 22nd century. Even more unsettling, a study released last year found that the space rock's path around the sun had been altered by about 100 miles (160 km) over the previous 12 years due to the Yarkovsky effect.

"We expect OSIRIS-REx will enable us to make an estimate of the Yarkovsky force on RQ36 at least twice as precise as what's available now," said Jason Dworkin, OSIRIS-REx project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

"What we want to be able to do is create a model that says okay if you give me an asteroid of this size, made of this composition, with this kind of topography, I can estimate for you what the Yarkovsky effect will be," Beshore explained in a Feb. 7 statement from NASA. "So now I can probably come up with a better notion of what to expect from other asteroids that I don't have the good fortune to have a spacecraft around."

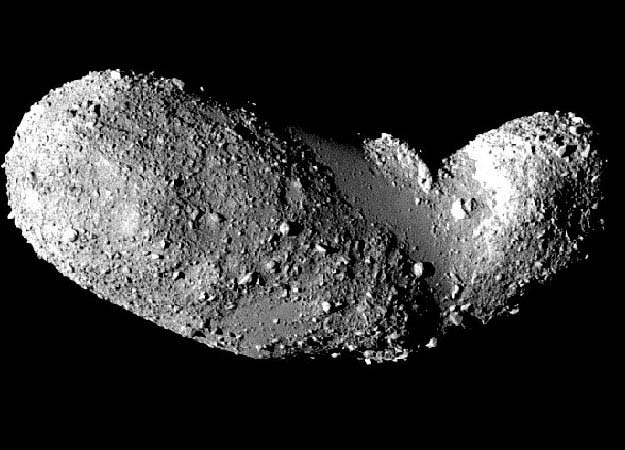

OSIRIS-REx, which will arrive at RQ36 in 2018 and orbit the asteroid until 2021, will be the United States' first asteroid sample-return effort and only the second mission in history to bring back samples from a space rock. Japan's Hayabusa spacecraft successfully returned tiny grains of the asteroid Itokawa to Earth in June 2010.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.