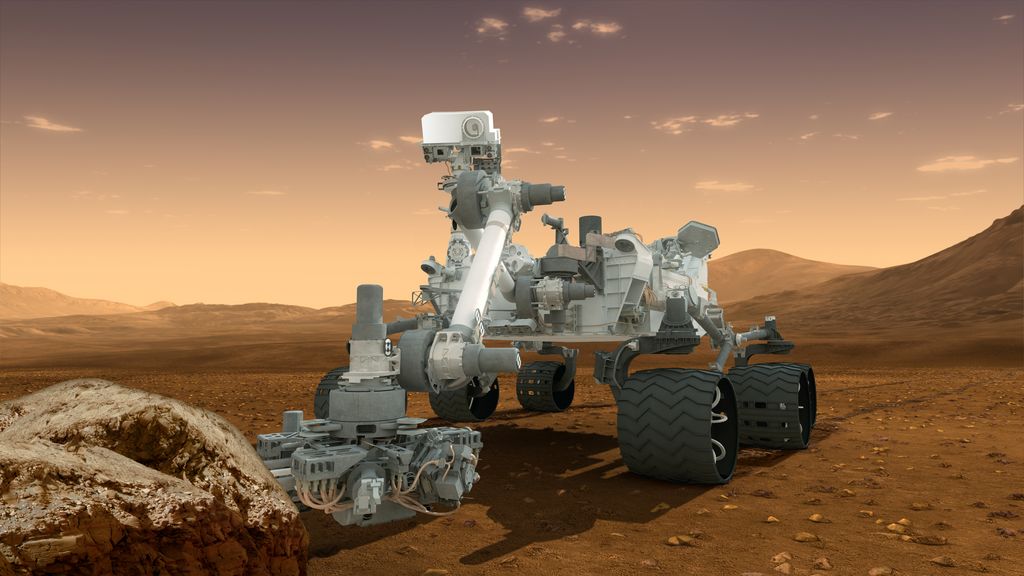

NASA's Curiosity rover has drilled into a Martian rock and collected samples, marking the first time any robot has ever performed this complicated maneuver on the surface of another planet.

The 1-ton Curiosity rover used its arm-mounted drill to bore a hole 0.63 inches (1.6 centimeters) wide and 2.5 inches (6.4 cm) deep in a section of sedimentary bedrock on Friday (Feb. 8). The activity paves the way for the first-ever analysis of fresh Martian subsurface material and provides the last major checkout of the robot's gear and instruments, researchers said.

"The most advanced planetary robot ever designed now is a fully operating analytical laboratory on Mars," John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, said in a statement. "This is the biggest milestone accomplishment for the Curiosity team since the sky-crane landing last August, another proud day for America."

Curiosity will process the sample over the next few days, researchers said. The rover will use some of the material to scour its sample-handling hardware clean of any residues that may remain from Earth before transferring any powder to the analytical instruments on the rover's body. [Curiosity Rover's Amazing Mars Photos]

"We'll take the powder we acquired and swish it around to scrub the internal surfaces of the drill bit assembly," said Curiosity drill systems engineer Scott McCloskey, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. "Then we'll use the arm to transfer the powder out of the drill into the scoop, which will be our first chance to see the acquired sample."

Drilling so deep into a Red Planet rock is a complex and unprecedented maneuver, so the mission team worked its way up to the first effort in a steady, stepwise fashion.

About two weeks ago, Curiosity began assessing the target rock, which is part of an outcrop called "John Klein" that was exposed to liquid water long ago. The rover first pressed down on the rock with its arm-mounted drill in a series of "pre-load" tests. It then used the drill's percussive action to hammer the outcrop without spinning the drill bit, which cleared the way for a recent "mini-drill" that bored into rock but didn't collect samples.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Getting Curiosity ready for all these steps — and for yesterday's successful full-up drilling run — also took a lot of prep work here on Earth, researchers said.

"Building a tool to interact forcefully with unpredictable rocks on Mars required an ambitious development and testing program," said JPL's Louise Jandura, chief engineer for Curiosity's sample system. "To get to the point of making this hole in a rock on Mars, we made eight drills and bored more than 1,200 holes in 20 types of rock on Earth."

Curiosity landed inside Mars' huge Gale Crater on the night of Aug. 5 to determine if the area has ever been capable of supporting microbial life. Along with its 10 science instruments and 17 cameras, the rover's drill is considered key to this quest, for it allows scientists to peer deep into Martian rocks for evidence of past habitability.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.