Space Rock! What You Need to Know About Friday's Asteroid Flyby

This Friday (Feb. 15), the asteroid 2012 DA14 will fly by Earth in an unprecedented close approach.

The event marks the closest-ever known approach by such a large near-Earth asteroid, and gives scientists a rare chance to take a good luck at a space rock as it whizzes by our planet.

To prepare for the historic event, here are some frequently asked questions about asteroid 2012 DA14, how it's monitored and what to expect during the flyby:

What is asteroid 2012 DA14?

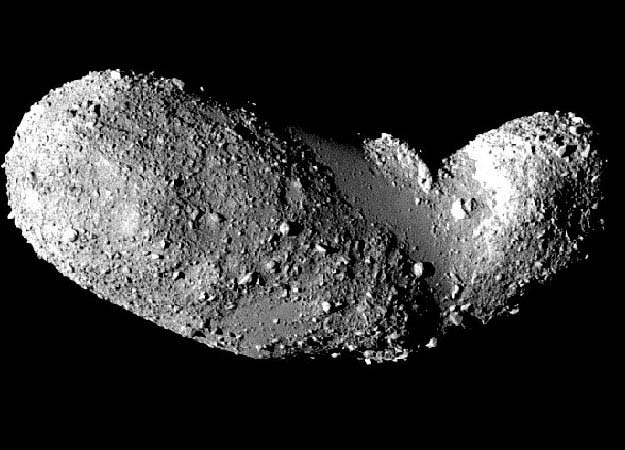

At 150 feet (45 meters) wide, asteroid 2012 DA14 is about half the size of a football field. It's also moving quickly. NASA researchers think the asteroid is making its way through the solar system at a blistering 17,450 mph (28,100 km/h). The asteroid is a stony space rock made of silicate material, making it an S-type asteroid. [See Photos of Asteroid 2012 DA14]

How close will the asteroid come to Earth?

During its closest approach over Sumatra, Indonesia, the space rock will be 17,200 miles (27,680 km) from Earth's surface on Friday at 2:24 p.m. EST (1924 GMT).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The asteroid will not only pass between Earth and the moon's orbit, but also fly lower than the ring of geosynchronous satellites high above the planet. Asteroid 2012 DA14 will be about 5,000 miles (8,046 km) closer to Earth than those satellites.

Will asteroid 2012 DA14 hit us?

There is no way the asteroid will hit the Earth or any of the satellites in orbit around the planet on this pass. Astronomers have mapped out the path of the asteroid so precisely that they know it cannot come within 17,100 miles (27,520 km) of the Earth's surface even given uncertainties about its trail.

NASA provided satellite operators with information about the asteroid's flyby well ahead of time just to be sure that no communications, weather or GPS satellites will be in the way of the asteroid as it passes.

What would happen if the asteroid hit, if it did?

NASA astronomers have compared the size of this asteroid with the one that caused the "Tunguska Event" over Siberia in 1908 that leveled trees across 825 square miles (2,137 square km).

Instead of smacking into the Earth's surface, asteroid 2012 DA14 would likely explode in midair, likely destroying whatever happens to be underneath it over a wide swath. [Asteroid 2012 DA14's Close Shave Explained (Infographic)]

Will the Feb. 15 flyby aim the asteroid back at us?

No, the flyby will not aim asteroid 2012 DA14 back in Earth's direction. NASA researchers have determined that the space rock will not make another close approach like this one in the foreseeable future.

How will NASA observe asteroid 2012 DA 14 during the flyby?

Because the space rock is too dim to see with the naked eye, researchers need to use sensitive ground-based telescopes to observe 2012 DA14. By observing in the infrared spectrum, researchers can see the heat of the sun reflected off the space rock to track its path.

NASA scientists are planning on using the Goldstone Solar Systems Radar located in California's Mojave Desert to keep tabs on the asteroid after it makes its closest approach.

Who monitors asteroids?

Assteroid 2012 DA14 was spotted last year by astronomers in Spain with the La Sagra Sky Survey at the Astronomical Observatory of Mallorca, and various space agencies around the world are responsible for keeping tabs on near-Earth objects that could pose a threat to the planet.

Experts heading NASA's Near Earth Object Program work closely with other agencies to monitor asteroids and comets that could be on a collision course with the planet. All the information they collect using radar imaging is transferred to a central database that astronomers around the world can use to help keep tabs on bodies that might be heading dangerously close Earth.

Amateur astronomers — like those who spotted 2012 DA14 — take part by watching out for asteroids that NASA adds to the list. After a certain number of observations, researchers can map the trajectory of the space rock to see exactly where and when an asteroid will fly by.

How often does an asteroid flyby like 2012 DA14's happen?

NASA researchers have estimated that a close approach for an object this size happens every 40 years, with a 2012 DA14-size space rock impacting Earth every 1,200 years.

How can I watch 2012 DA14's flyby?

The asteroid's closest approach happens during daylight for most skywatchers in the Western Hemisphere, but stargazers in many parts of the Eastern Hemisphere could catch a glimpse of its flyby.

Although it can't be seen with the naked eye, a small telescope pointed in the right part of the sky could help amateur astronomers see the fast-moving rock. It will look like a small pinprick of light moving quickly from north to south.

NASA will also be live-streaming the flyby via a telescope at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. ET (2200 to 200 Feb. 16 GMT) on Friday.

You can follow SPACE.com's complete coverage of asteroid 2012 DA14 flyby here.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter @mirikramer or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.