Russian Meteor Explosion Outshone Sun

The fireball that exploded over Russia Friday morning (Feb. 15) provided onlookers with an incredible spectacle, even outshining the sun for a brief period, scientists say.

The meteor exploded just above the city of Chelyabinsk just before 9:30 a.m. local time, damaging hundreds of buildings and injuring more than 1,000 people. The blast probably released about 300 kilotons of energy, sending out a powerful shockwave and lighting up the daytime sky, researchers said.

"This event must have been brighter than the sun, if you were there to watch it," Paul Chodas, a scientist with the Near Earth Object Program Office at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., told reporters today. "It's just incredible."

The object that caused the Russian meteor was probably about 50 feet (15 meters) wide and weighed approximately 7,000 tons, said Bill Cooke of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. [See Photos of the Meteor Streaking over Russia]

This space rock exploded 12 to 15 miles (19 to 24 kilometers) above Earth's surface, releasing roughly 15 times as much energy as the atomic bomb the United States dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima during World War II.

The resulting blast shattered windows and knocked down walls, according to media reports.

"When you hear about injuries, those are undoubtedly due to the shockwave," Cooke said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The fireball hit Earth's atmosphere at about 40,000 mph (64,374 kph) and left a trail 300 miles (483 kilometers) long in the sky, he added.

Although the explosion did shoot fragments of the rock toward the ground, there have been no confirmed reports of recovered pieces of the space rock, Cooke said.

Scientists have a particularly difficult time tracking small asteroids like the one that exploded earlier today because they are so small and dim. The Russian meteor was particularly difficult to spot because it came from the daylight side of the planet. Telescopes can only detect meteors in the dark, Cooke said.

Space rocks like the Russian fireball hit the Earth once every 50 to 100 years, he added.

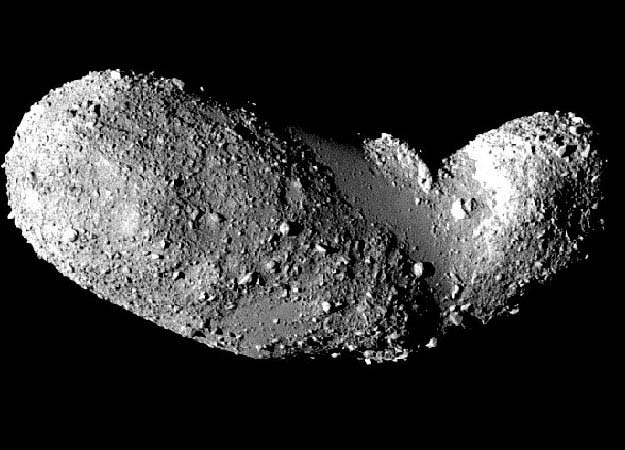

Most asteroids are loose masses of rock, and NASA experts think this meteor probably fit that description. As the fireball entered the atmosphere, it started to break apart and eventually exploded when the heat generated by its dramatic plunge toward the Earth's surface became too great.

This is the most powerful meteor explosion of its kind since the Tunguska Event 1908, researchers said. The meteor that exploded that year over the Tunguska region of Russia's Siberia was probably 130 feet (40 m) in diameter and flattened 825 square miles (2,137 square km) of forest.

A meteor similar to today's fireball exploded in the air over Indonesia in 2009, but it didn't cause nearly this amount of damage. This most recent meteor explosion was probably four to five times more powerful than the 2009 event, Cooke said.

By coincidence, the Russian fireball exploded on the same day that the 150-foot-wide (45 m) asteroid 2012 DA14 cruised within 17,200 miles (27,000 km) of Earth. 2012 DA14's flyby was the closest by such a large asteroid that scientists have ever known about in advance. The two space rocks that made big news today are completely separate bodies, Cooke and Chodas stressed.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter @mirikramer or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.