Origins of Massive Star Explosions May Be Found

The key to a supernova's future is in its past, scientists say.

A new study, unveiled today (March 7), may help astronomers turn back the clock on supernovas to understand how some of these massive cosmic explosions, which signal the death of stars, can occur.

By reviewing observations of 188 supernova remnants, study leader Xiaofeng Wang, an astronomer at Tsinghua University in Beijing, and his team discovered a seemingly simple way to understand what the "progenitor" star of a stellar explosion may have looked like before the white dwarf went supernova.

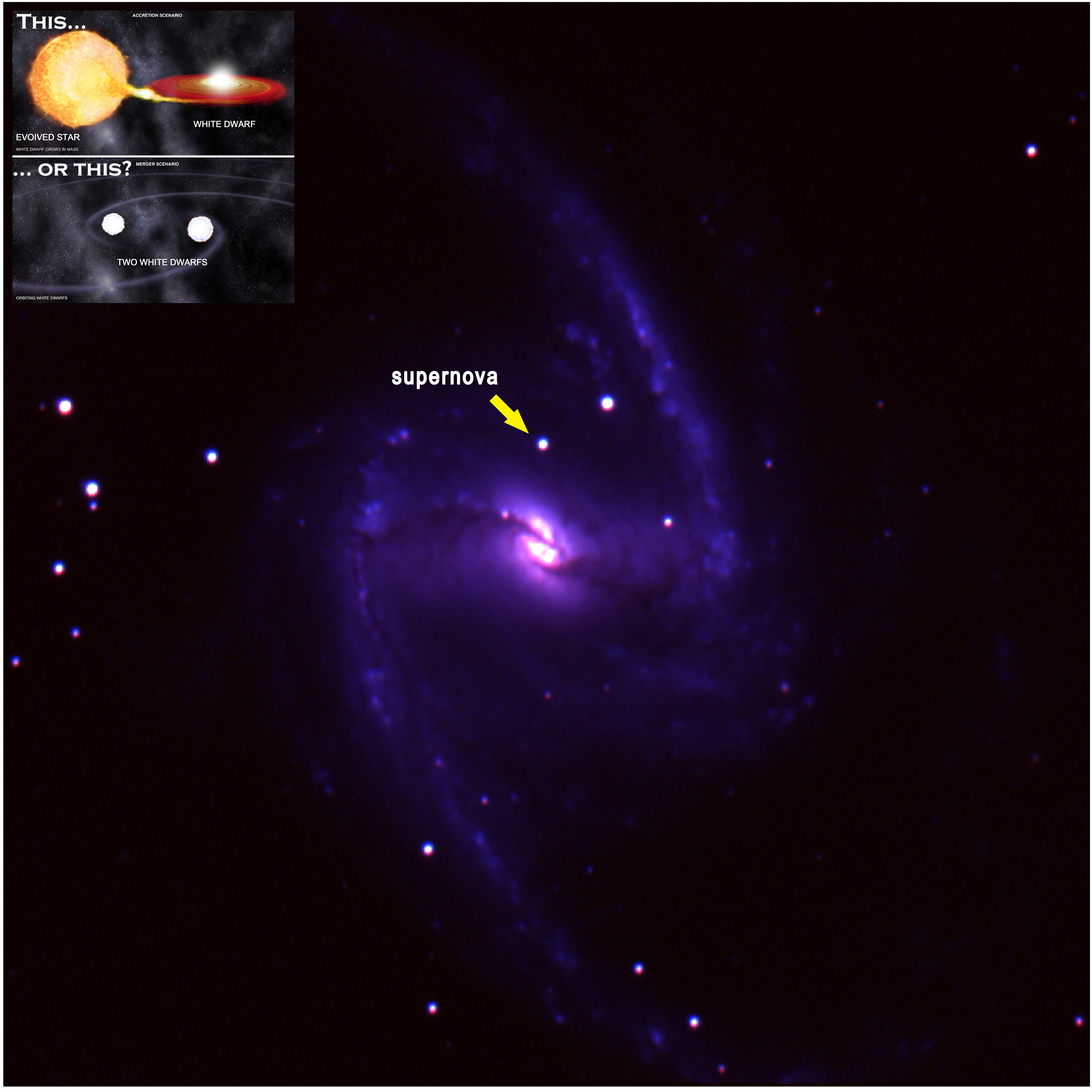

Wang and his team focused specifically on a kind of star explosion known as a Type 1a supernova, which astronomers use as cosmic mile-markers to measure vast distances across galaxies. Astronomers know that Type 1a supernovas can form in one of two different scenarios, both of which include a small, dying star known as a white dwarf that is about the size of Earth, but as massive as the sun.

The team analyzed the general galactic locations of the supernovas in their survey in order to understand what the area could have looked like at the time of the actual explosion. They found the stars that went supernova in more metal-rich, and possibly younger, star systems exploded more violently than supernovas born in less metal-rich areas of a galaxy.

"The typical mass of a white dwarf is not large enough to trigger an explosion; it is suggested that either merging of two white dwarfs in a binary system or continuous accretion of mass from a companion by a white dwarf is required to reach that limit," Wang said. "But the evidence from observations are not strong enough to support one scenario and refute another one." [Amazing Photos of Supernova Explosions]

These results are one more step toward solving a mystery that has beleaguered scientists researching supernovas since the 1960s.It is likely that the more explosive supernovas are caused by a white dwarf extracting mass from a companion star like the sun or a red giant, but not another white dwarf, Wang said. The less violent supernovas are probably caused by the merging of two white dwarfs.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The basic idea is that we use these supernovae to measure distances," Ryan Foley, an astronomer at Harvard who was not involved with the study, said. "It's how we know the universe is expanding. That's great, that we measure distances with them, but it's embarrassing that we don't yet know what stellar systems produce them."

While Wang's work is consistent with other findings, by using a broad overview of survey data, the results are not as detailed as some supernova research published in recent years, added Foley.

An earlier study led by Foley used a comprehensive examination of a group of Type 1a supernovas to see that the violently exploding stars were found in gassy environments within their area of the galaxy.

"The previous way that we've found the differences is telescope time-intensive; this new way has the potential to use very little telescope time," Foley said of Wang's work. "Overall, it's a nice result, but it's one of these things that the interpretation of the results is going to take a little time to flush out."

The research was detailed online March 7 in the journal Science.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.