Scientists Hope to Extend Mercury Spacecraft's Mission

The first spacecraft ever to orbit the planet Mercury is nearing the end of its mission — unless its science team has anything to say about it.

Researchers have petitioned NASA for a two-year mission extension on the Messenger spacecraft, which has already spent two years orbiting the closest planet to the sun. As of now, the probe is only authorized to continue operating through March 17.

"We recently submitted another proposal to go for two more years, and it would end when we run out of propellant and Messenger eventually impacts the surface of Mercury," said Messenger principal investigator Sean Solomon of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

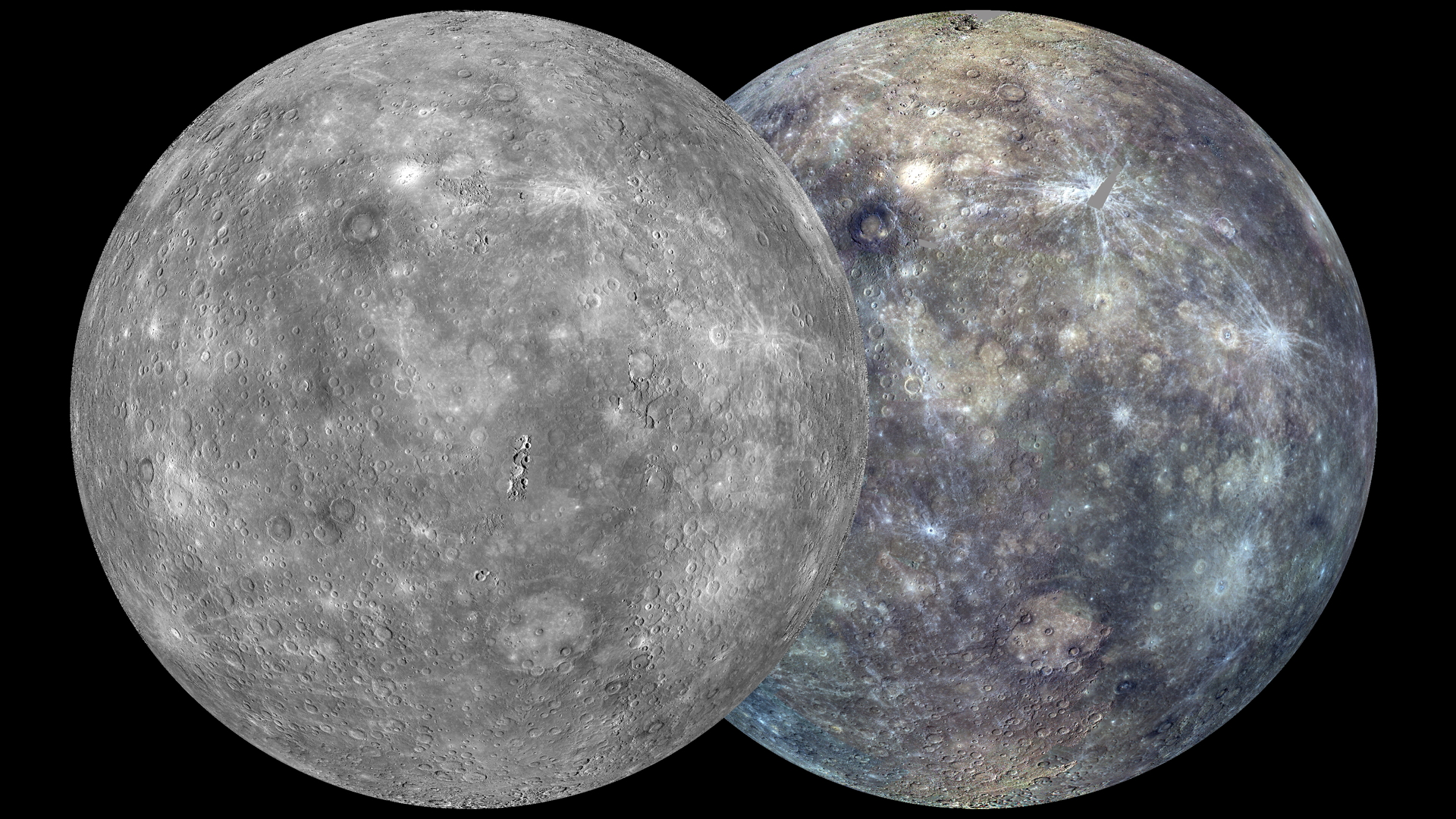

The $446 million Messenger (which stands for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) arrived at the planet in March 2011 and has already fully mapped Mercury's surface for the first time. But there's still much to accomplish with the probe, scientists say.

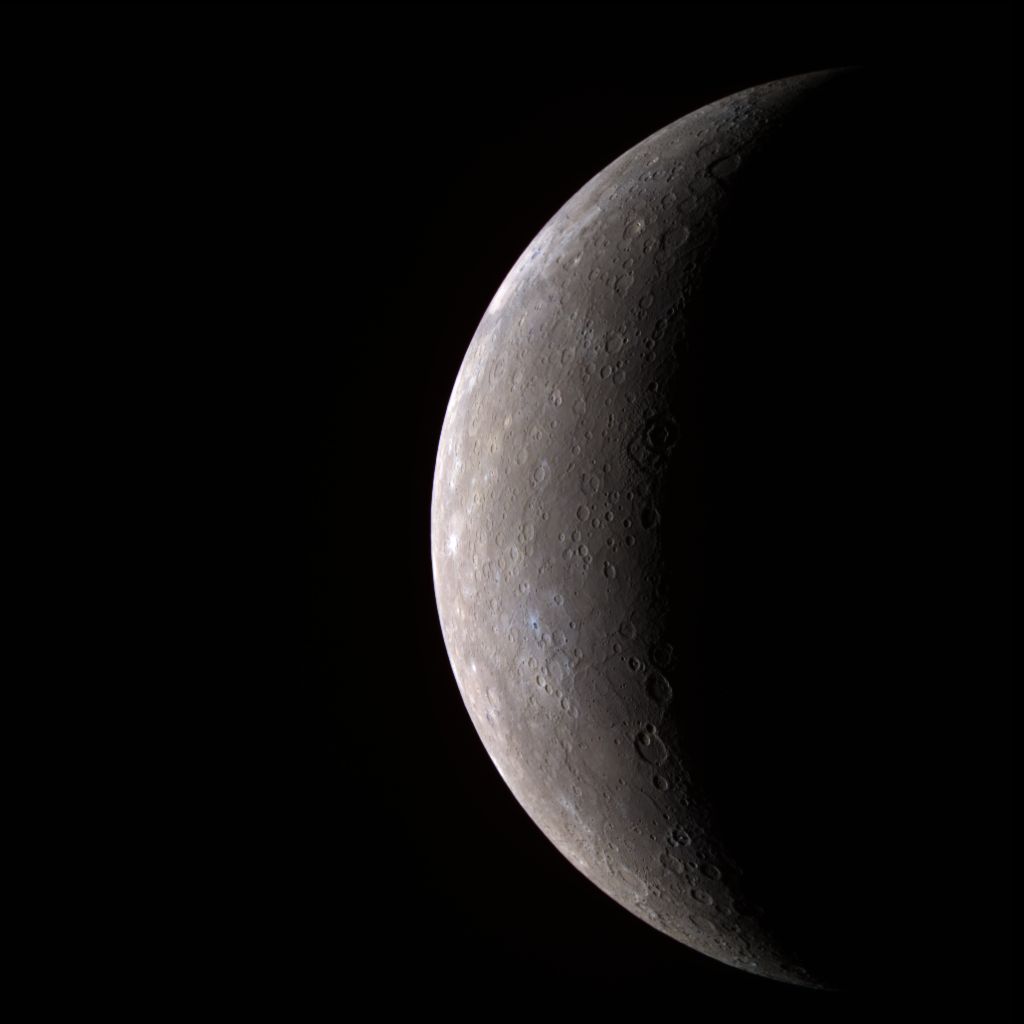

For example, Messenger is due to slowly lose altitude after about another year as it runs out of fuel and heads toward its demise. If the probe's instruments remain operating, these closer approaches provide an unprecedented opportunity. [Latest Mercury Photos by NASA's Messenger]

"When we're 25 kilometers or less away from the planet, we'll be seeing things at 10 times the resolution of our best images to date," Solomon told SPACE.com. "We'll be closer than any mission has been to the planet, and we'll probably be seeing things we've never seen before. It'll be one of the most exciting times of the mission."

The extended mission would also allow Messenger to make targeted observations of areas of interest on the planet, such as the intriguing "hollows" features the probe first discovered in 2011, which scientists suspect may be created when volatile elements are sublimated off the surface.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Additionally, the probe would observe a pair of comets that are due to make close approaches to the sun in November of this year. One of them, Comet ISON, has the potential to become so bright it could be visible from Earth with the naked eye.

"Messenger will have a perspective on that comet that will be different from Earth-based observatories or spacecraft," Solomon said.

And if Messenger continues operating, it will also have a front row seat to the sun's maximum phase of activity this year, when solar flares and eruptions are expected to ramp up.

But none of these goals will be possible if the spacecraft team runs out of money.

"If we do not receive approval for an extended mission then we would stop taking data, and the spacecraft would not have these low-altitude campaigns and would just impact the surface with nobody listening."

The Messenger team expects a response from the scientific review panel weighing its extension proposal in April, and NASA officials have said the probe can continue operating until its future has been decided.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookor Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.