Mars Announcement Raises Question: What Is Life?

NASA officials announced March 12 that ancient Mars could have supported primitive life. But this begs the question: What exactly constitutes life?

Merriam-Webster.com defines life as "an organismic state characterized by capacity for metabolism, growth, reaction to stimuli and reproduction." But there's no single satisfactory definition of life.

"I think it is a mistake to try to define life, because we have only one example of life, familiar life on Earth, and we have reason to believe that this example may be unrepresentative of life in general," Carol Cleland, a philosopher of science at the University of Colorado, Boulder, told LiveScience in an email.

Defining life

Aristotle made the first attempt at a definition, describing life as something that grows, maintains itself and reproduces. But this definition would exclude mules, which are sterile, while including things like fire.

Calling life something that has a metabolism, the ability to take in energy to grow or move and excrete waste, is no good either; cars do this, for example.

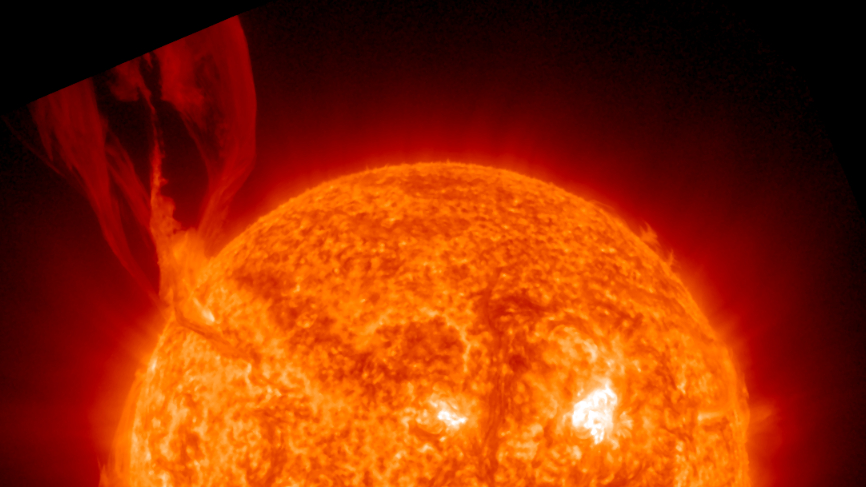

In 1944, the physicist Erwin Schrödinger gave life a definition based on the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy, or disorder, of a closed system increases over time. Schrödinger defined life as something that decreases or maintains its entropy. Yet this definition fails because it includes crystals, which resist entropy by forming highly structured lattices.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Trying to define life by its qualities is the wrong approach, Cleland said. As an example, she cites scientists' early attempts to define water in terms of properties like being wet, transparent and a good solvent. "We didn't 'define' water as H2O, but rather discovered, in the context of molecular theory, that it is a chemical substance composed mostly of H2O molecules," Cleland said.

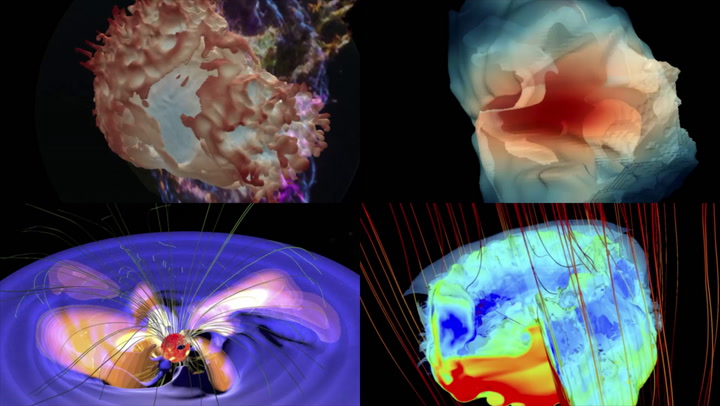

Life on Earth is typically divided into two main groups: the cellular life forms, which include archaea, bacteria and eukarya (all the plants and animals), and non-cellular life forms, like viruses. Whether viruses, which can replicate only inside the cells of a host organism, count as "life" is debated.

Life in the universe

Finding an airtight definition for life may not be so important, astrobiologist Chris McKay of NASA's Ames Research Center in California wrote in an email to LiveScience. It's "much better to have an idea of what life is built of," McKay said. "Life is built of complex, organic molecules."

Characterizing life is vital for identifying it elsewhere in the universe, a possibility now beyond the realm of science fiction. McKay said that if life exists somewhere else, it would be a material system evolving through reproduction, mutation and natural selection. [9 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

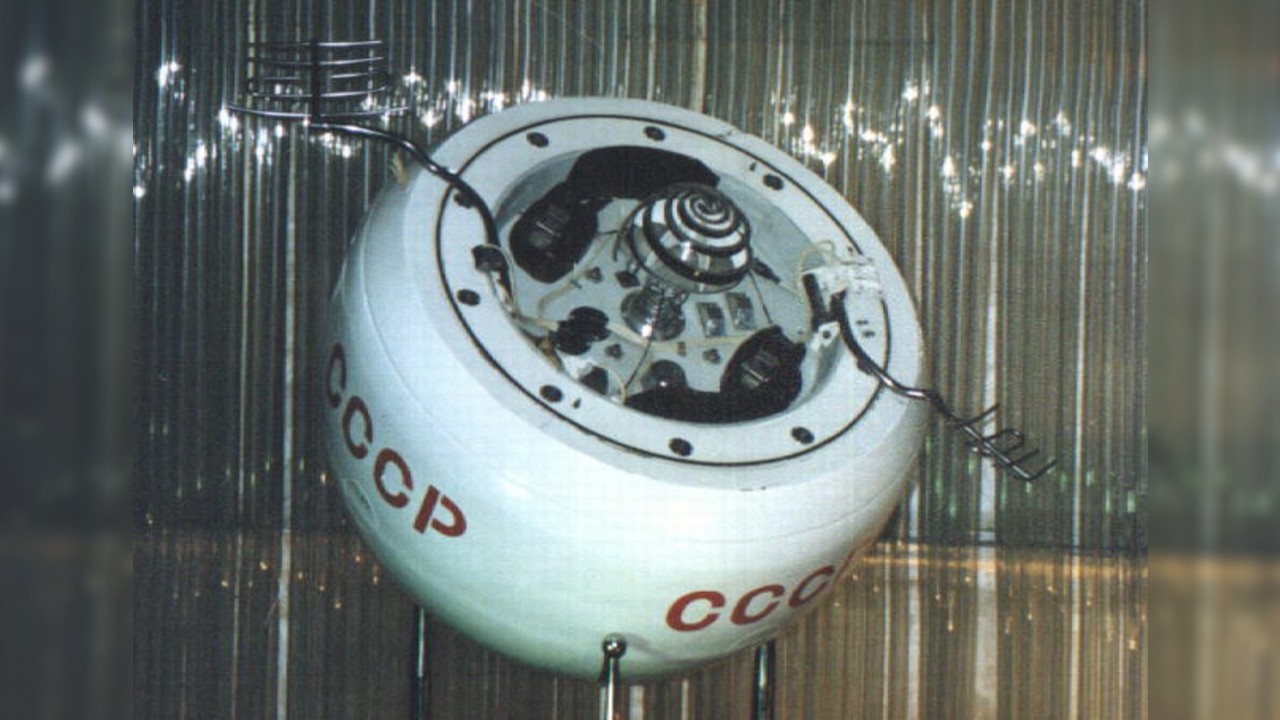

Beyond Earth, one of the first places humans have sought to find life is Mars. The Viking Mission in the 1970s looked for evidence of life in the Martian soil. One experiment appeared to find evidence of metabolic reactions, but these were dismissed as coming from a non-living source (though some still debate those results).

With the announcement that NASA's Curiosity rover has found evidence that life could have once existed on Mars, Curiosity has answered the question it set out to study in November 2011. The finding comes just seven months after the rover landed on the Red Planet on Aug. 5, 2012.

Given that Mars could have supported life, McKay said, "Now we need to look for it."

This story was provided by LiveScience, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Tanya Lewis @tanyalewis314. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.