The devastating wildfires of 2021 are breaking records and satellites are tracking it all

Wildfires in Siberia have broken a record for annual fire-related emissions of carbon dioxide.

It's been a summer of climate-related disasters around the world. A landmark United Nations report on climate change, released on Monday (Aug. 9), confirmed the trend: the planet is not coping with human influences on its climate and the situation is bound to get worse.

This year, record-breaking wildfires triggered by similarly historic heatwaves are ravaging swaths of land on three continents and Earth observation satellites — some operated by space agencies and others by private companies — have been tracking it all, just as they've done for years.

In the U.S., the Dixie Fire has become the largest wildfire in the history of California, having destroyed more than 700 square miles (1,811 square kilometers) of land (as of Aug.8). European countries around the Mediterranean Sea, such as Greece, Turkey and Italy, have been forced to evacuate residents as well as tourists from several of their usually paradise-like holiday destinations. In Siberia, the sparsely inhabited region in the north-east of Russia, out of control wildfires have already broken annual records for fire-related emissions of greenhouse gases.

Related: Wildfires are turning the sun and moon red

Wildfires in Siberia set worrying records

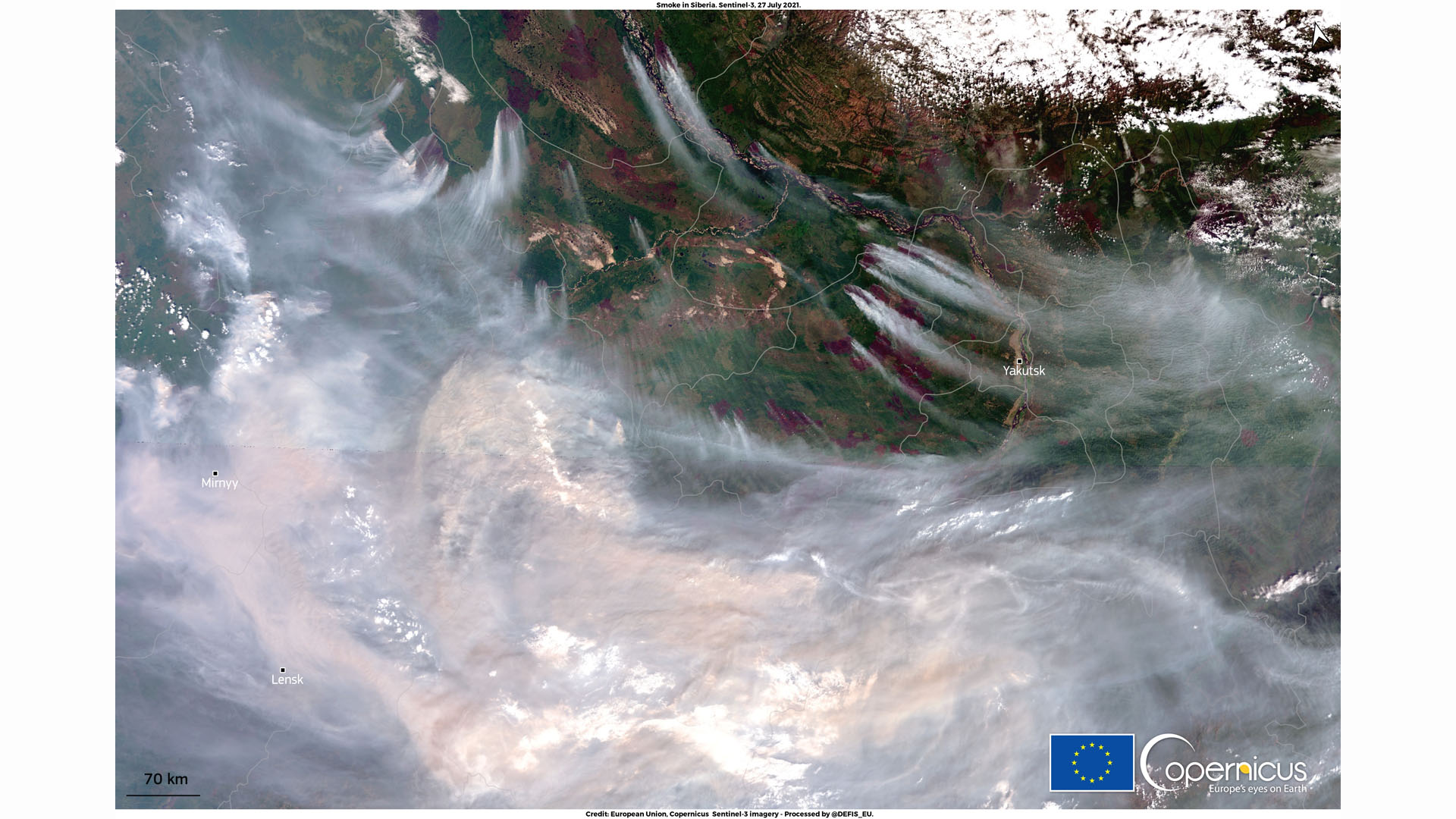

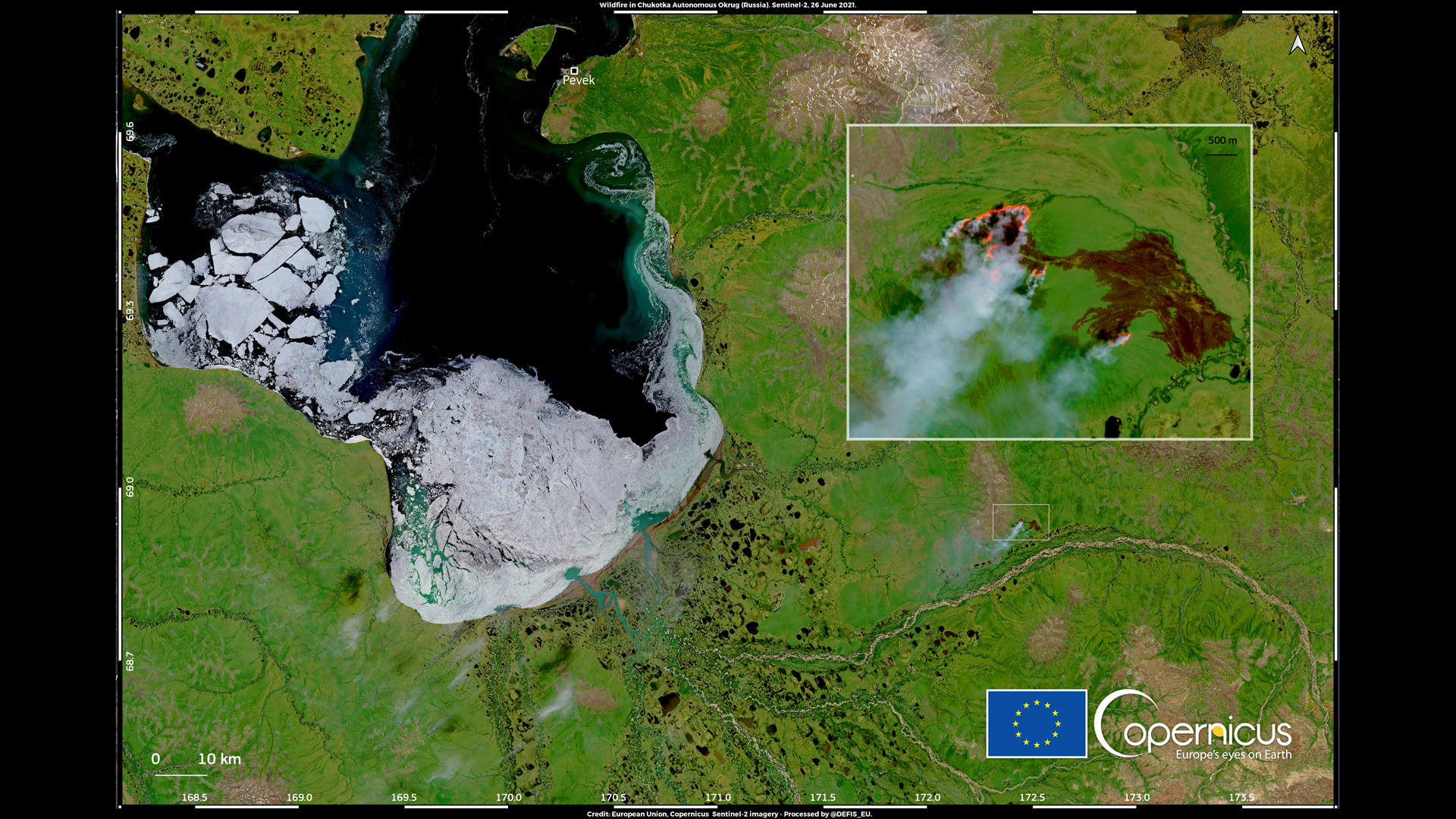

The Russian fires in Siberia may be occupying fewer news pages and less air-time, but they actually worry scientists the most. Since late spring, satellites have been supplying images of vast areas of taiga near the polar circle being devoured by flames. Russian authorities, in many places, have given up the fight.

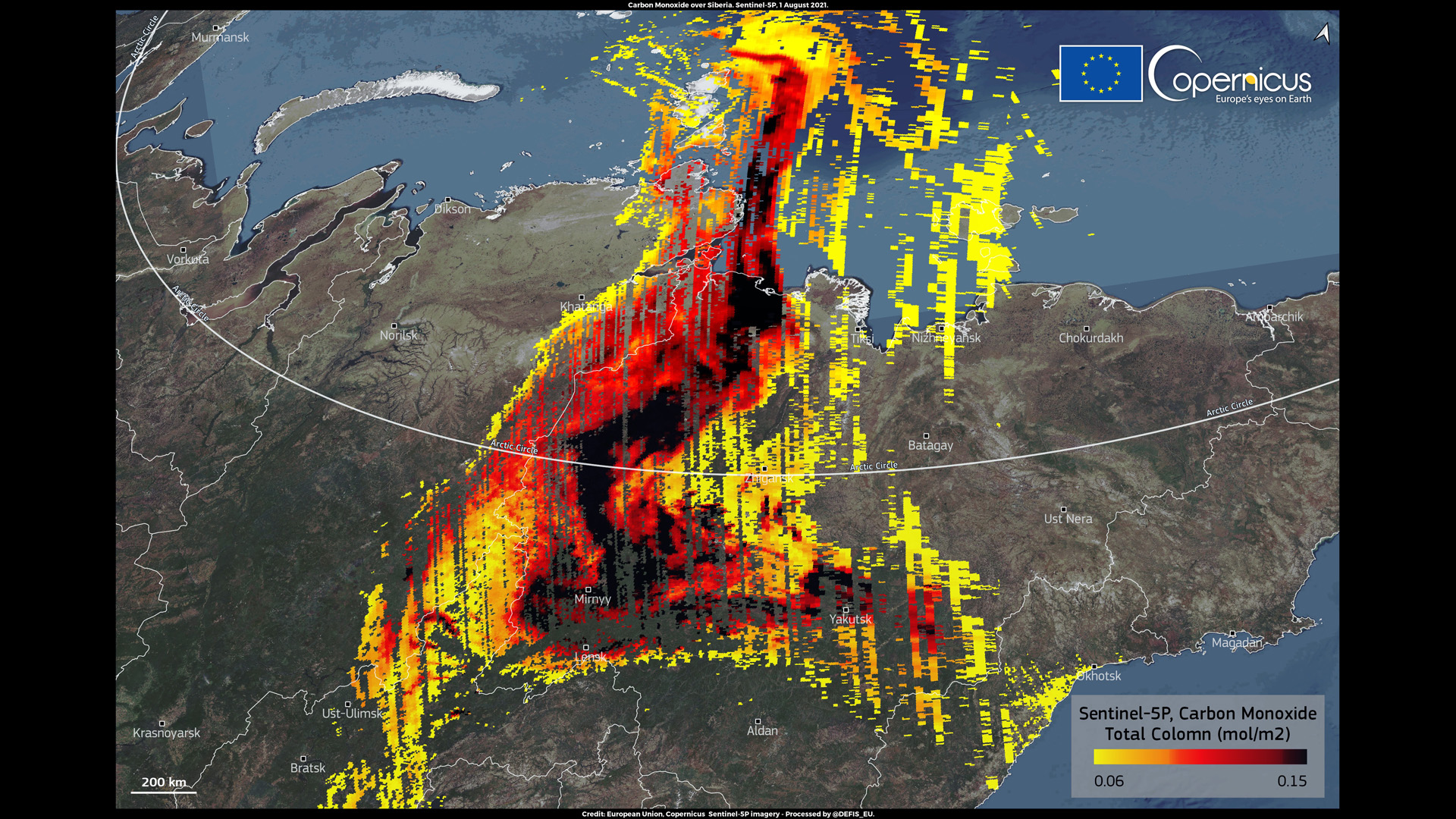

"In the Sakha Republic and the whole Far Eastern Federal District of Russia, we are already seeing the total estimated fire emissions from the region exceeding last year's levels," Mark Parrington, a senior scientist at the European Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), told Space.com. "Our data set goes back to 2003. And this year, in terms of the total estimated emissions, it's already much higher than the previous record annual total, which was 2020."

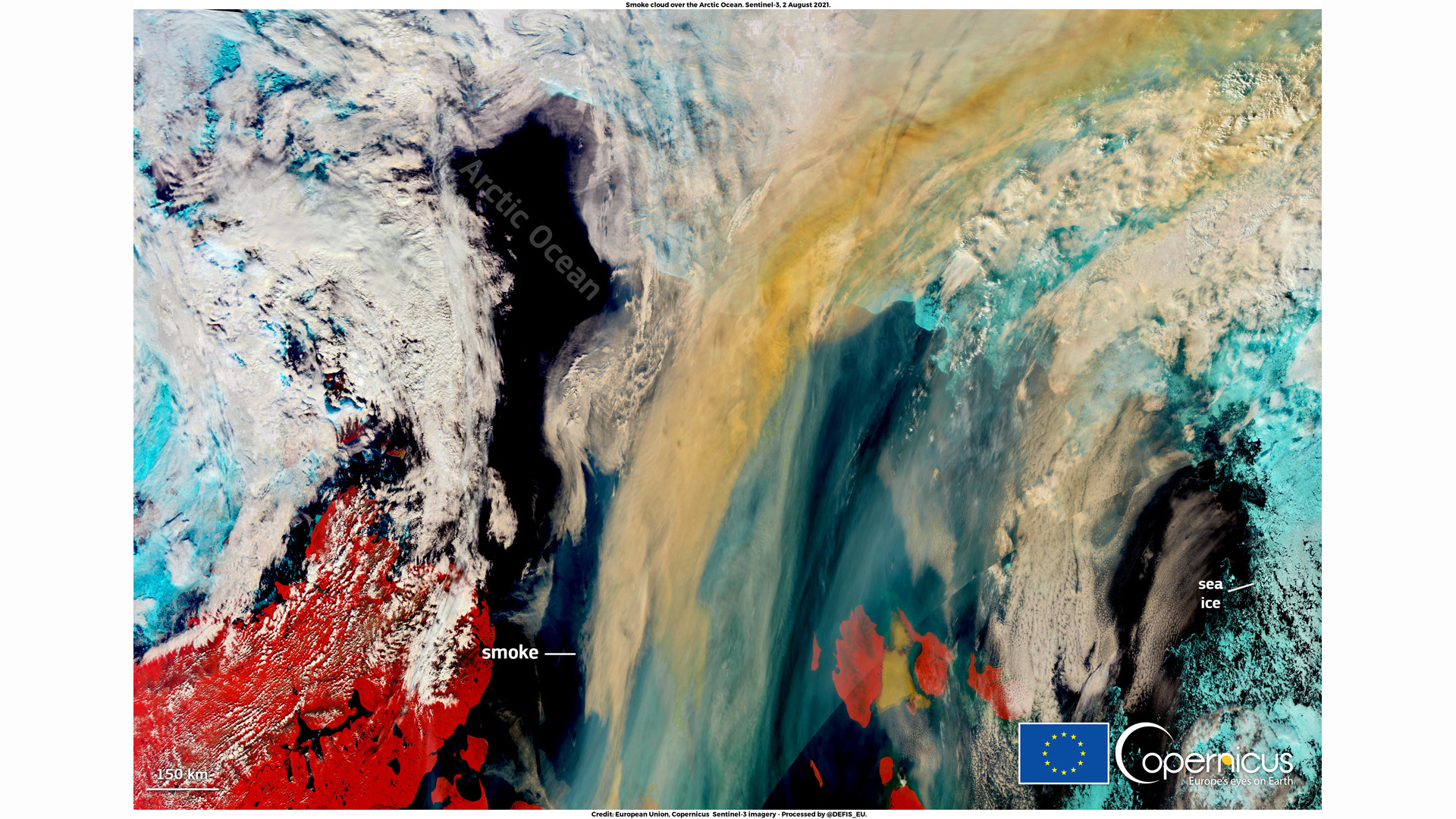

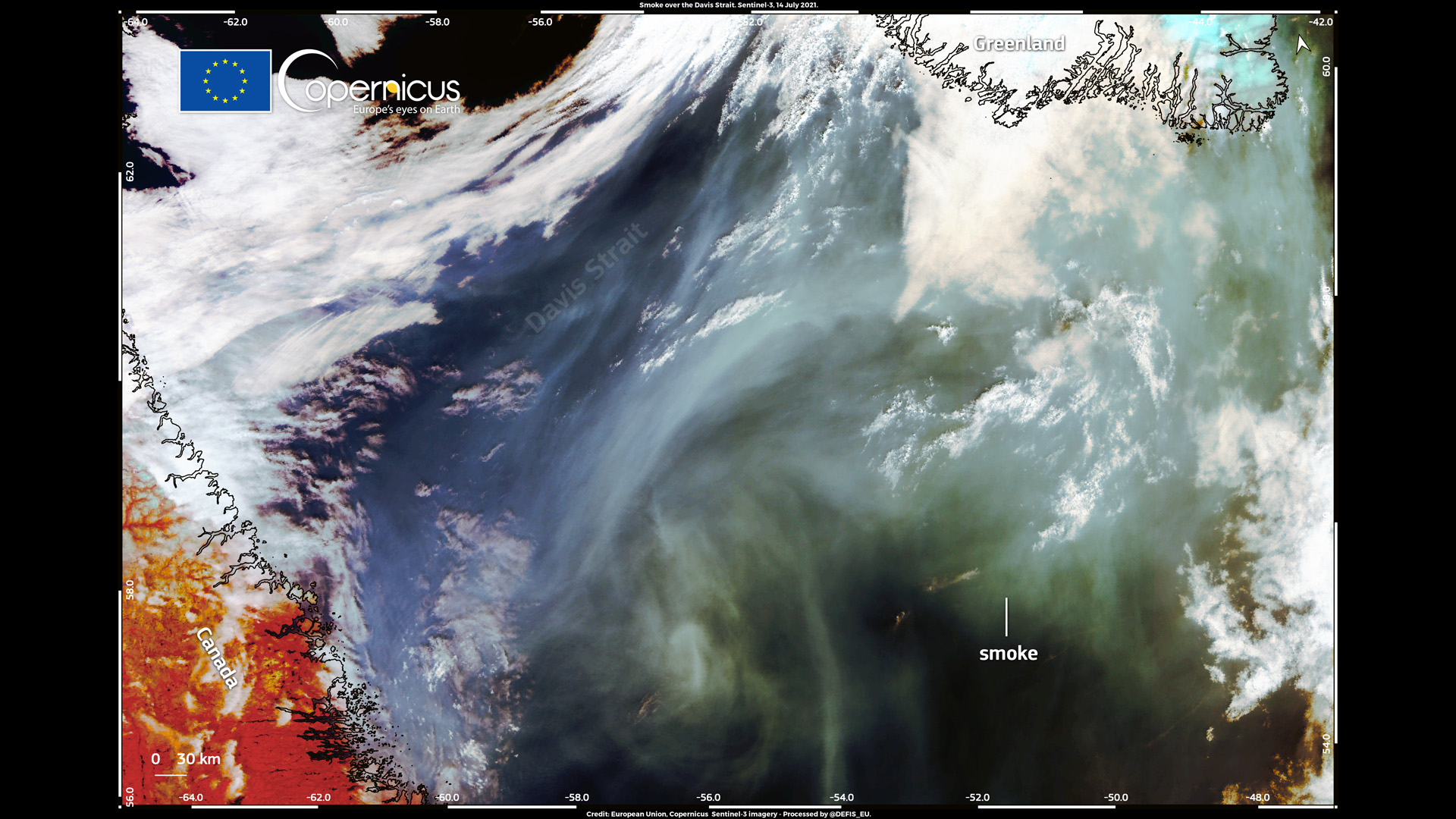

Plume of smoke from record-breaking wildfires in Siberia spreading towards North Pole.

Wildfires in Siberia have produced a record amount of CO2

Siberian wildfires are by far the worst this year

A wildfire raging close to one of Russia's northernmost towns

According to CAMS data, wildfires in Siberia emitted since June more than 188 megatonnes of carbon, which is equivalent to about 505 megatonnes of carbon dioxide. In comparison, Europe’s biggest polluter Germany emitted 750 megatonnes carbon dioxide in the entire year 2018.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The region, which has experienced record-breaking temperatures in June, has lost almost 19,300 square miles (500,000 square kilometers) of vegetation to the fires, according to end of July estimates.

Last week, the Sentinel 3 satellite, part of the Copernicus constellation, captured a 930 miles (1,500 km) long plume of smoke generated by the wildfires spreading from the Republic of Sakha over the Arctic Ocean and into the Arctic Circle towards the North Pole. That, according to Parrington, is not good news.

"We are quite concerned about the potential deposition of the particulate matter [from the smoke] onto the sea ice," Parrington said. "That has the potential to accelerate sea ice melting because the darkened surface absorbs more heat."

It's not just forests that are on fire in the region but also peatlands, an important natural carbon sink, which, according to Parrington, will not recover its ability to store carbon once the blaze subsides.

Fires in western U.S. out of control for weeks

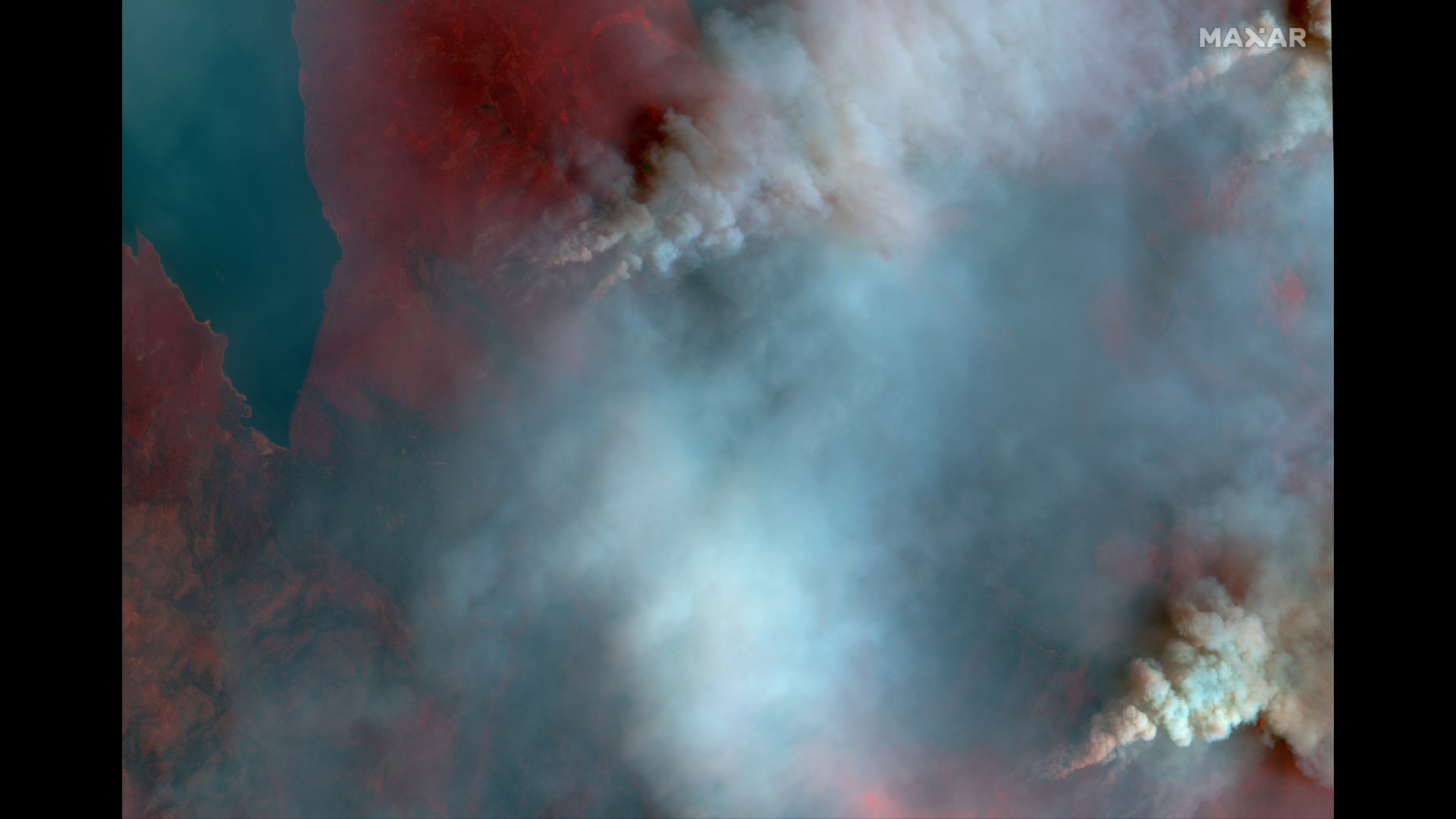

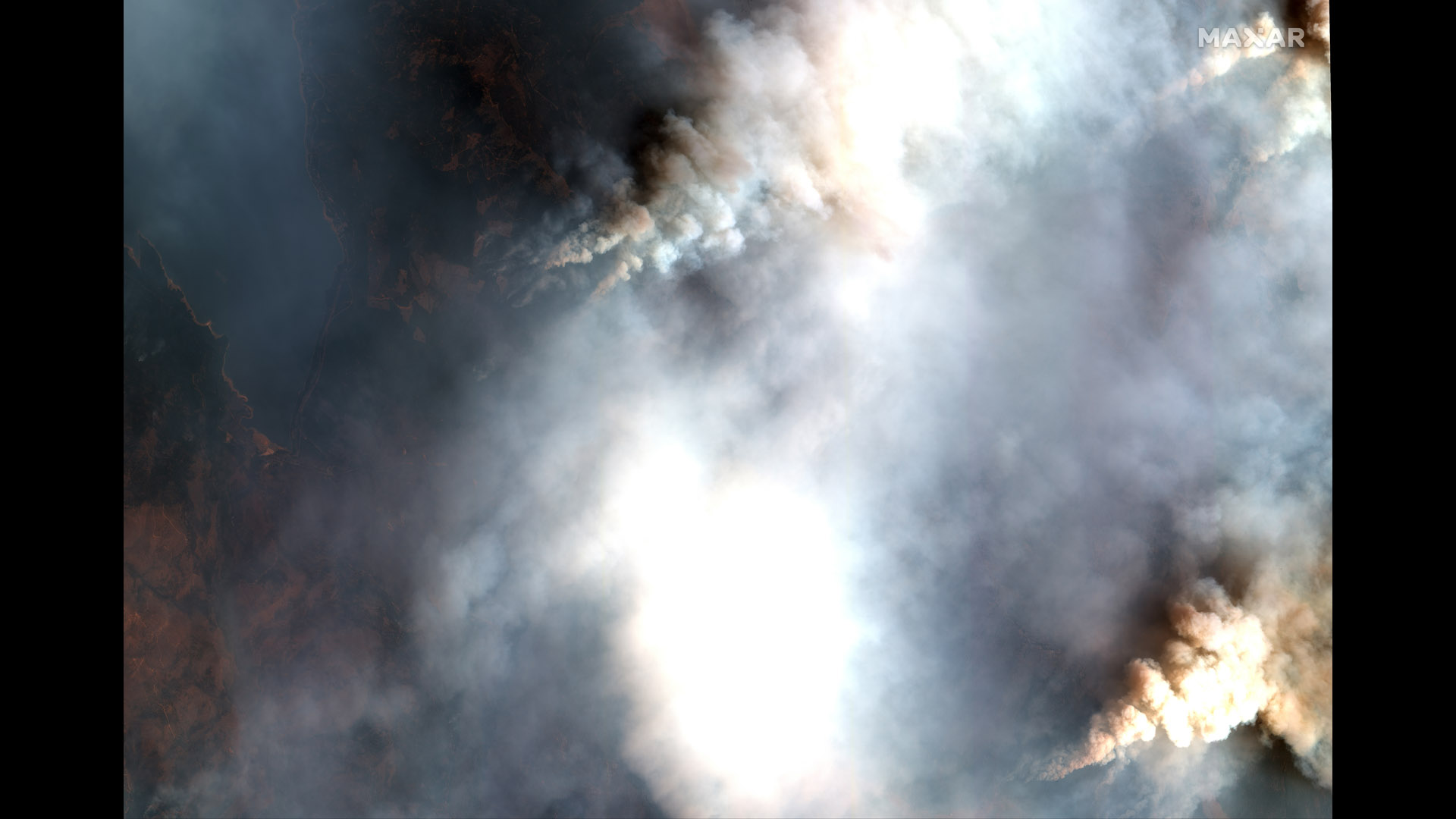

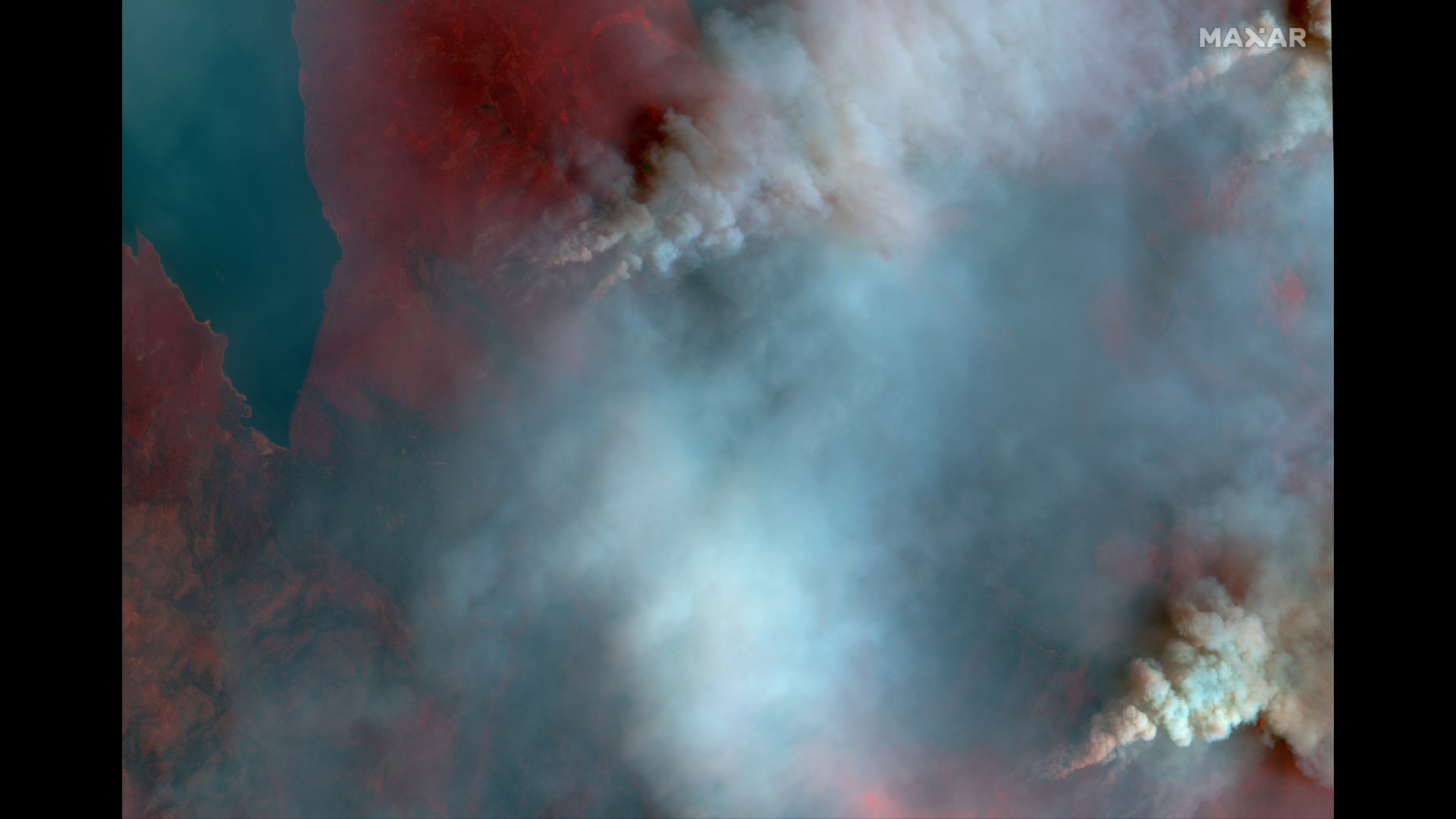

Lake Almanor at the epicenter of the devastating Dixie Fire in California.

Lake Almanor hit by Dixie Fire in infrared

Lake Almanor before fire

Lake Almanor hit by the Dixie Fire

A cloud of wildfire smoke spreading towards the Atlantic Ocean

Fires in the western United States, triggered by a record-breaking heatwave last month, have started later than those in Siberia, but have too grown into record-breaking proportions. The Dixie Fire, which started on July 13 in northern California, is still out of control after nearly a month of struggle.

Images, acquired by satellites of U.S. Earth observation company Maxar Technologies (in the gallery), show forests around Lake Almanor, in northeastern California, ravaged by the fire. The fire also devoured the historic mining town of Greenville, burning to the ground many of its early 19th century buildings.

Firefighters have only managed to contain about 20% of the fire, which continues to be fuelled by high temperatures, low humidity and strong winds.

Smoke from the fire has spread all the way to low-lying areas of northern California, including Sacramento and San Francisco.

According to Parrington, air pollution from wildfires can frequently spread across distances of thousands of miles.

"Wildfire smoke is quite hazardous and quite toxic to human health," Parrington said. "And we are seeing severely degraded air quality in all the regions downwind of these fires."

Mediterranean paradise turning into hell

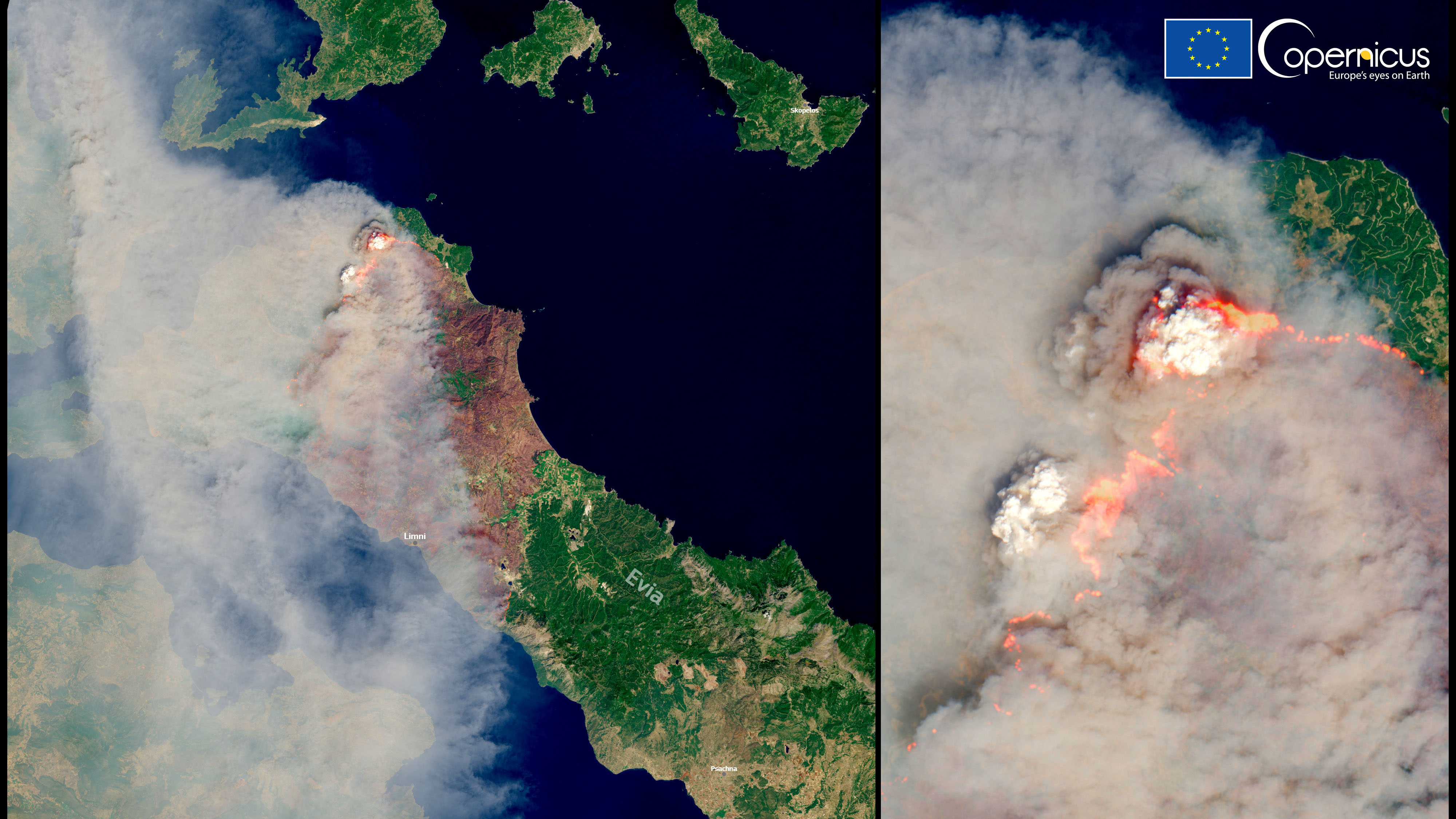

Forest on the Greek island of Evia destroyed in a wildfire

The Greek island of Evia after a wildfire

Wildfire raging on the Greek island of Evia in August 2021

Smoke hovering above the Evia island

The 2021 wildfires in Turkey have been described as the worst in a decade

The usually hot Mediterranean region has experienced higher than usual temperatures this summer. In Turkey and Cyprus, temperatures have soared to over 120 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius). Greece has experienced slightly lower temperatures of 115 degrees F (45 degrees C). The heat combined with dry conditions turned the Mediterranean vegetation into a tinderbox.

The wildfires in Turkey have been described as the worst in at least a decade. Greece's currently worst fire rages on the island of Evia, about 60 miles (100 kilometers) from the country's capital Athens. But firefighters are struggling with dozens of fires all over the country, as well as in neighboring Italy.

"In all these areas, the U.S. northwest, Siberia and the Mediterranean, we would expect some fires in summer," Parrington said. "But the common feature this year is unusual heatwaves and dryer surface conditions, which means the fire risk is high. As a result, we see those fires burning for way longer periods of time than we would normally see."

Although fire activity depends on meteorological conditions that can vary each year, Parrington said, the overall situation is likely going to get worse in the future as the climate in many of these areas becomes hotter and drier in summer months.

Out of the three areas currently hit by devastating fires, Siberia seems to be experiencing a continuously worsening trend for at least the past five years, Parrington said. The previous year of record-breaking wildfire emissions was 2020, which saw many unexpected wildfires erupting behind the polar circle. Multiple of them survived the winter smouldering in the peat as zombie fires only to be fanned back to life in spring when temperatures got warmer.

"You get high years and low years so that makes it really difficult to say with any certainty what we expect to see next year or the following years," Parrington said.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.