The top 7 black hole discoveries from 2024

Space.com was on duty all year to bring you the major developments in the science of the universe's most fascinating entities: black holes.

- Fasting-growing black hole eats a sun a day!

- 1st binary stars found around the Milky Way's supermassive black hole

- 1st 'black hole triple' discovered

- Elusive intermediate-mass black holes come out of hiding

- Supermassive black hole throws a tantrum

- Gaia discovers sleeping giant black hole close to Earth

- A new look at 'our' supermassive black hole

Our fascination with black holes is pretty understandable; their one-way boundary, the "event horizon," traps light, meaning no signal can ever travel from inside a black hole to outside. The edge of the black hole is thus a region of space and time that expressly forbids interlopers. That's a recipe for mystery. And we all love a mystery, especially scientists.

This is compounded by the fact that at the center of the black hole lies a singularity, at which point all our laws of physics break down, making gibberish of even our most nuanced and profound achievements in physics. Approach the event horizon of a black hole on a one-way mission of discovery, and even if you survive, your distant colleagues won't be able to wave you away. Because time and space warp so dramatically at that point, you'll forever appear frozen at the edge of the event horizon.

That doesn't mean we know nothing about these cosmic titans, however. Each year, humanity makes more discoveries about black holes, some of them shocking, some of them reassuring (they are the ideal laboratories to test and confirm general relativity, our best theory of gravity), and some of them just plain weird.

The last 12 months have been no excpetion to this progress. Space.com is proud to guide you through the most important black hole discoveries of 2024.

1) Fasting-growing black hole eats a sun a day!

As Christmas 2024 rolls over to New Year 2025, many of us will turn our minds to diets to offset the effects of our annual period of overindulgence. In February 2024, astronomers discovered a distant black hole that is the master of overindulgence.

The supermassive black hole is so far from Earth that it has taken 12 billion years for the light emitted by material around it to reach us. It is visible at almost the dawn of time because this monster, with a mass of between 17 billion and 19 billion times that of the sun, powers the brightest quasar ever seen by humanity.

Maintaining this emission requires the black hole to consume the equivalent of the mass of the sun in gas and dust every day!

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We have discovered the fastest-growing black hole known to date. It has a mass of 17 billion suns and eats just over a sun per day," discovery team leader and Australian National University astronomer Christian Wolf said in a statement. "This makes it the most luminous object in the known universe."

This quasar, designated J0529-4351, is so luminous that if placed next to the sun, it would be 500 trillion times brighter than our star! Might as well take the Christmas lights down early.

Read more: Brightest quasar ever seen is powered by black hole that eats a 'sun a day'

2) 1st binary stars found around the Milky Way's supermassive black hole

Binary stars are pretty common, with over half of all stars predicted to share space with a partner. So you might be surprised to find the discovery of a binary star system on this list (especially since it is supposed to be about black holes, and this is only entry two, darn it).

However, this discovery isn't really about what astronomers found; it's where they found it. In mid-December 2024, scientists discovered a pair of binary stars designated D9 orbiting each other close to Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way.

This is extraordinary because the immense gravity of Sgr A*, which has a mass of around 4.2 million times that of the sun, and that of other supermassive black holes was thought to be too destructive to allow binary stars to exist nearby.

Though D9 is relatively young at just 2.7 million years old (compared to our 4.6 billion-year-old sun, anyway) and its discoverers expect that its two stars will soon be forced to merge, this discovery indicates that the environments around supermassive black holes might not be as turbulent as feared.

That means there is the possibility that planets may even form, albeit briefly, around the high-velocity stars whipped around by the gravity of Sgr A*.

"Black holes are not as destructive as we thought," research lead author and University of Cologne scientist Florian Peißker said in a statement." It seems plausible that the detection of planets in the galactic center is just a matter of time."

3) 1st 'black hole triple' discovered

Cleary "two is company" for some stars orbiting black holes, but in October 2024 astronomers discovered to their surprise that some stars in triple systems allow a companion to stick around even after it has transformed into a black hole.

This knowledge came via the discovery of the first "black hole triple," consisting of a black hole hungrily feeding on a companion star while being orbited by a more distant, cautious star.

The system V404 Cygni, which is located within the Milky Way about 8,000 light-years from Earth, was already known to astronomers and had been well studied, but it was only this year that scientists linked the more distant star with the system.

The discovery is important because it implies that black holes can form in a more gentle way that doesn't "kick away" more loosely bound distant stars like the supernova explosions usually thought to accompany black hole birth would.

"This system is super exciting for black hole evolution, and it also raises questions of whether there are more triples out there," Kevin Burdge from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) told Space.com via email. "The fact that this star is still bound is surprising because it implies it received a low-energy natal kick.

"Overall, it's not surprising that black holes should be in triples because a large fraction of massive stars are in triples, but what's surprising is that this system held onto the triple after forming the black hole."

Read more: 1st triple black hole system discovered in 'happy accident'

4) Elusive intermediate-mass black holes come out of hiding

Thus far on this list, we've talked about supermassive black holes with masses of millions to billions of times that of the sun and stellar-mass black holes with a much smaller mass range of 10 to 1,000 solar masses. But there must be some black holes between these two classes of black holes.

Indeed there are. Intermediate-mass black holes are thought to sit within this mass gap, acting as a "missing link" that helps some black holes reach supermassive status. The prefix "missing" applies because this class of black hole has been frustratingly elusive.

In July of 2024, using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers caught sight of what they believe is a missing link black hole in Omega Centauri, the remains of a galaxy long ago cannibalized by the Milky Way.

This act of cosmic cannibalism deprived this intermediate-mass black hole of the food it needed to grow past its mass of 8,200 times that of the sun, effectively "freezing it in time."

"At a distance of about 18,000 light-years, this is the closest known example of a massive black hole," team member and Max Planck Institute for Astronomy Ph.D. student Maximilian Häberle said in a statement.

The following month, a separate team of researchers discovered evidence of a different intermediate-mass black hole, this time lurking near the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) at the heart of the Milky Way, some 27,000 light-years from Earth.

You wait ages for a medium-sized black hole, and then two turn up nearly at once.

Read more: Hubble Space Telescope finds closest massive black hole to Earth — a cosmic clue frozen in time

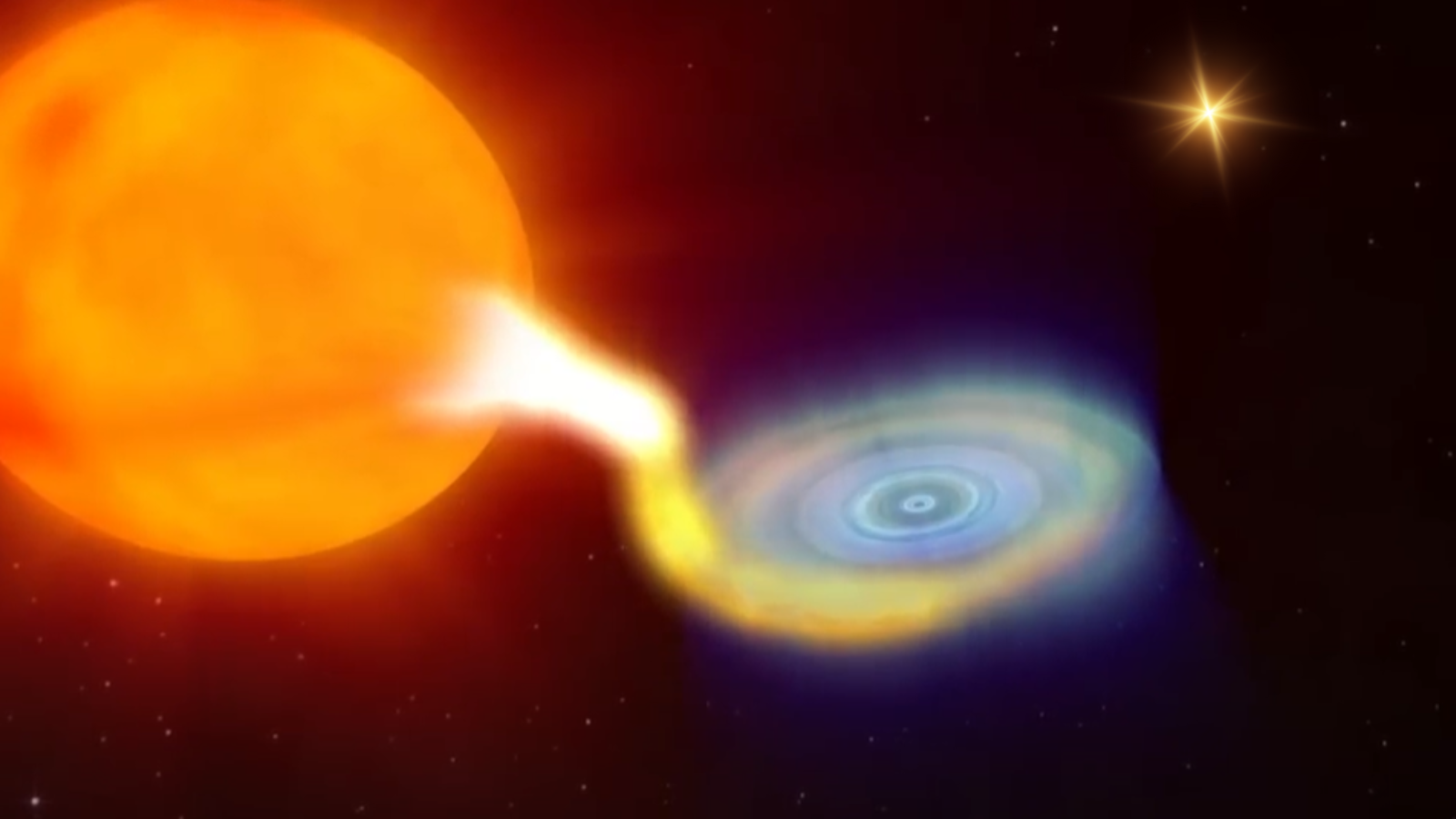

5) Supermassive black hole throws a tantrum

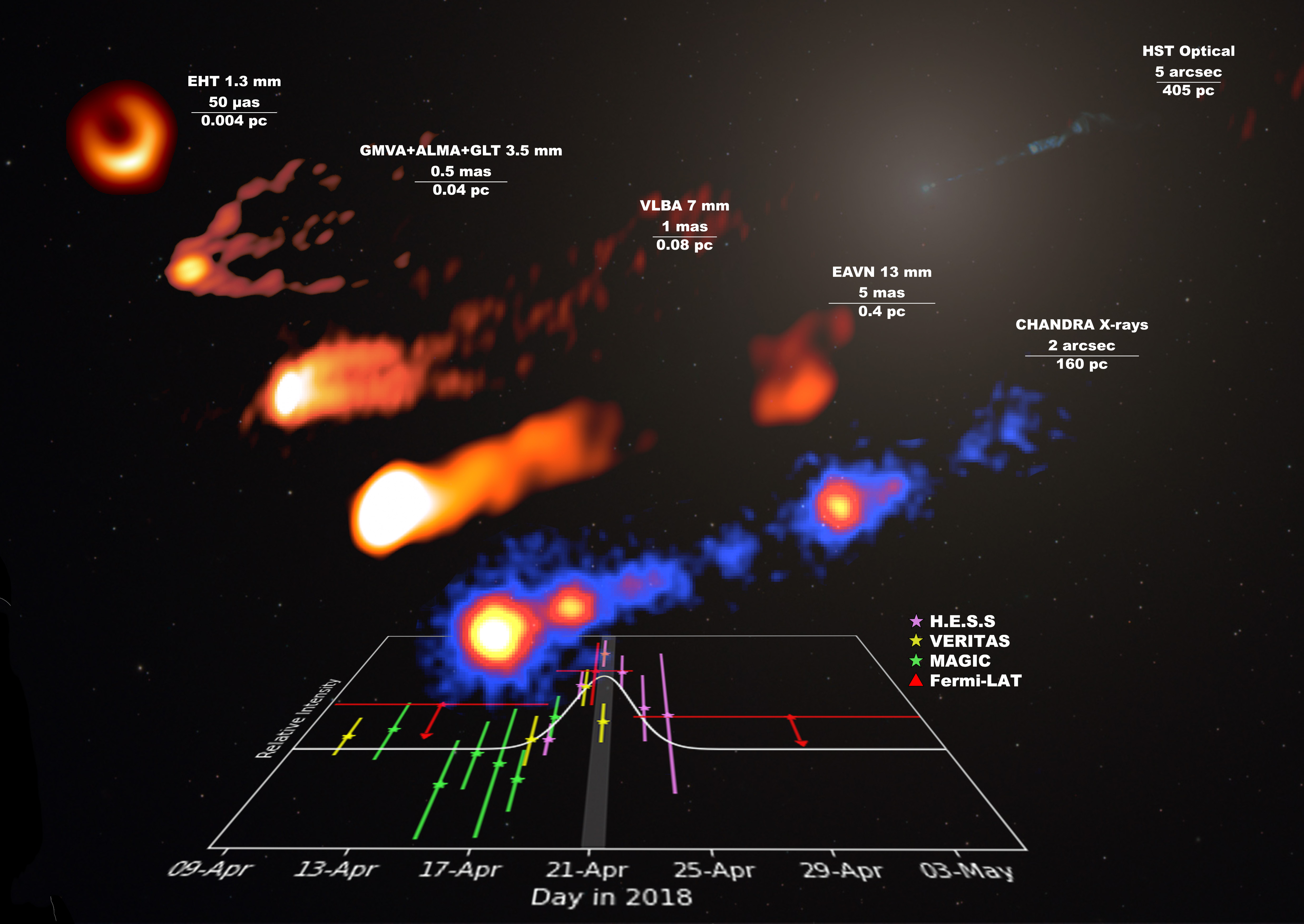

In 2018, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) revealed to the world the first image of a black hole, namely the supermassive black hole at the heart of the distant galaxy Messier 87 (M87).

Six years later, the study of this black hole, designated M87*, which has a mass equal to about 5.4 billion suns, by the EHT is still delivering important science. In December 2024, the scientists behind the project revealed that the EHT, comprised of telescopes around the globe that form a virtual Earth-sized instrument, witnessed the same black hole erupt with a powerful and unexpected explosion.

This gamma-ray flare lasted for three days at the end of April 2018. Not only was this the first time M87* has flared since 2010, but this blast was more energetic than previous emissions.

By studying this blast, EHT scientists hope to learn more about the structure around supermassive black holes, particularly the flattened disks of gas and dust that feed them called accretion disks. The emission has already revealed that the jet of high-speed particles erupting from M87* at near-light speed stretches so far that its emergence from M87* was compared to a blue whale erupting from a single bacteria.

"In particular, these results offer the first-ever chance to identify the point at which the particles that cause the flare are accelerated, which could potentially resolve a long-standing debate about the origin of cosmic rays [very high-energy particles] from space detected on Earth," team leader and University of Trieste researcher Giacomo Principe said in a statement.

Read more: 1st monster black hole ever pictured erupts with surprise gamma-ray explosion

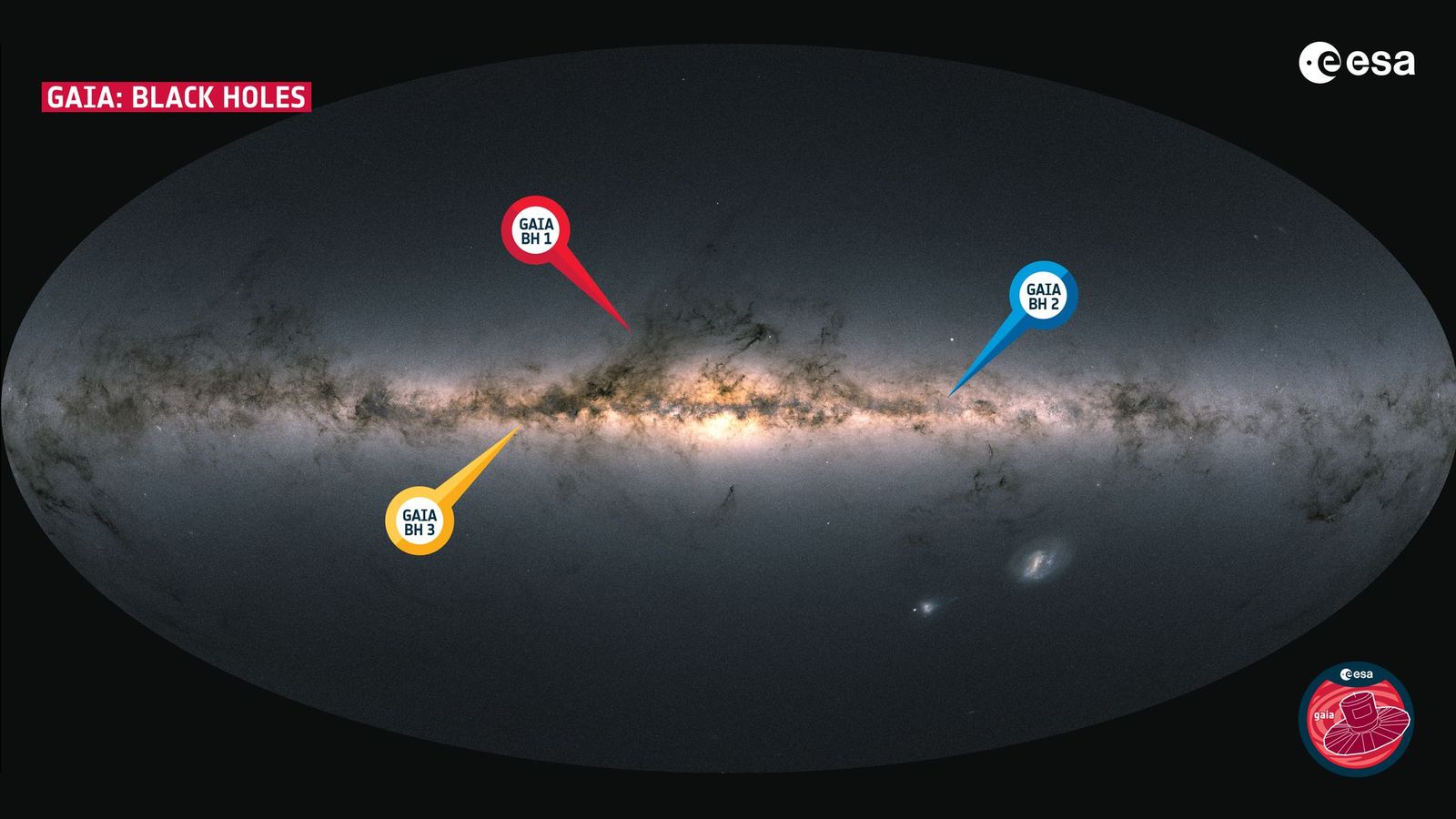

6) Gaia discovers sleeping giant black hole close to Earth

In April 2024, the star-tracking space telescope Gaia discovered its third black hole. Not only is this black hole, known as "BH3," the second closest to Earth at just 2,000 light-years away (the closest black hole, BH1, was also discovered by Gaia, but in 2023), it is also a bit of a monster.

BH3 has a mass equivalent to around 33 suns. While that means it pales into insignificance compared to supermassive black holes, compared to other close stellar-mass black holes, BH3 is pretty monstrous. It's a bit like comparing Frankenstein's monster to Godzilla.

This was the first time that such a massive stellar-mass black hole has been found close to Earth.

"Finding Gaia BH3 is like the moment in the film 'The Matrix' where Neo starts to 'see' the matrix," George Seabroke, a scientist at Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London and a member of Gaia's Black Hole Task Force, said in a statement sent to Space.com. "In our case, 'the matrix' is our galaxy’s population of dormant stellar black holes, which were hidden from us before Gaia detected them."

The discovery team's lead researcher, Pasquale Panuzzo of CNRS, Observatoire de Paris in France, said in a statement: "This is the kind of discovery you make once in your research life."

7) A new look at 'our' supermassive black hole

This list has taken us out to the very edge of the observable universe to look at some of the earliest black holes. What better way to wrap up than returning home to pop in on Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole at the heart of our galaxy?

This isn't just a cursory visit, though; Sgr A* was making news in 2024, particularly in March, when the EHT caught a new aspect of the familiar black hole. The Earth-sized virtual telescope was able to capture Sgr A* in polarized light for the first time.

Not only did this new observation reveal that powerful magnetic fields are well organized around Sgr A* just as they are around the much more massive M87*, but it hinted at an undiscovered feature about our black hole.

"We expect strong and ordered magnetic fields to be directly linked to the launching of jets as we observed for M87*," Sara Issaoun, research co-leader and NASA Hubble Fellowship Program Einstein Fellow at the Center for Astrophysics (CfA) at Harvard & Smithsonian told Space.com. "Since Sgr A*, with no observed jet, seems to have a very similar geometry, perhaps there is also a jet lurking in Sgr A* waiting to be observed, which would be super exciting!"

Maybe further evidence of such a jet will manifest itself in 2025.

As mentioned above, black holes like to keep their secrets close to their hearts, so who knows what major developments will make it to this list in twelve months as 2025 draws to a close.

One thing that is no mystery, however: Just as we have been for the past quarter of a century, Space.com will be there in 2025 to document every step taken in the quest to understand black holes, and we hope you will be right there beside us.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.