The promising Comet ISON continues on its way in toward a late November rendezvous with the sun, cosmic close encounter that will bring the celestial object to within 800,000 miles (1.2 million km) of the sun's surface.

Many have already christened ISON as the "Comet of the Century," but this may be premature, since the comet’s performance will hinge chiefly on whether it can survive its extremely close approach to the sun on Nov. 28. During that encounter, the comet will approach close to the sun's surface —called the photosphere— while also plunging through its intensely hot corona whose temperature exceeds 1 million degrees Fahrenheit (555,000 degrees Celsius).

A comet that performs well en route toward the sun — that is, steadily brightens as it comes closer – would seem more likely to survive as opposed to an object that brightens more slowly, or fails to brighten much at all. In the latter case, perhaps the volatile material which boiled off the comet’s core (called the nucleus) and initially made the comet look unusually bright becomes exhausted while the comet is still far out in space.

The result is a comet that is nothing more than a small and dark solid lump that fails to get very bright at all or perhaps even fragments or disintegrates as it comes to within a hairbreadth of the sun. [Photos of Comet ISON]

Has ISON's brightness has slowed?

This pessimistic scenario might be one that may be ruminating through the minds of some comet observers now concerning Comet ISON.

Astronomers measure the brightness of objects in the night sky on a scale of magnitude on which smaller numbers represent brighter objects, with negative numbers denoting exceptionally bright objects. Since Comet ISON's discovery in September 2012, the comet has brightened only a little, from magnitude +17.3 on Oct. 15 to magnitude +15.5 as of a couple of weeks ago.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To get an idea of just how faint this is, the comet is currently visible to the eye only under dark, pristine skies and by using telescopes with very large apertures of around 30 inches. Most of the observations of the comet so far have been made through the use of long exposure photographs or image sensors such as a charge-coupled device (CCD).

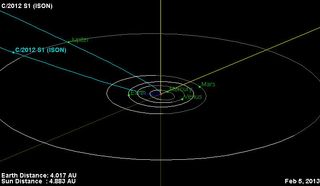

Still too early to tell

Comet ISON is still very far from the Earth (386 million miles or 621 million kilometers), as well as the sun (403 million miles or 648 million km). The comet was discovered in September 2012 by Russian amateur astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok using the International Scientific Optical Network. Comet ISON's official designation is C/2012 S1 (ISON).

On March 6, John Bortle, a highly regarded amateur observer who has viewed hundreds of comets spanning over five decades, wrote this assessment of Comet ISON:

"The much hyped Comet ISON is not evolving in the fashion we had earlier anticipated. Rather than slowly but steadily gaining in brightness it has stagnated at basically near 16th magnitude for a couple of months now. After experiencing an interval where the coma's degree of condensation grew quite strong, the object threw out an unexpected strong but short tail that has persists right down to today. However, following this episode the coma subsequently faded, became less condensed and smaller, all bad signs regarding the "health" of the comet's nucleus. Whether ISON becomes a Great Comet next fall, or just another in a long string of Great Flops, is now much more a question than ever before."

SPACE.com will continue to monitor the progress of Comet ISON in the weeks and months to come. We plan to post another update in late April.

The Comet Pan-STARRS has dominated the attention of comet observers in the Northern Hemisphere throughout March and still remains an exciting target for stargazers. The comet made its closest approach to the sun on March 10, and became visible to the unaided eye for some stargazers soon afterward. It was appearing low on the western horizon just after sunset, which made the comet hard to spot for some due to the bright twilight.

You find out how to see Comet Pan-STARRS here.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing picture of Comet ISON, Pan-STARRS or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.