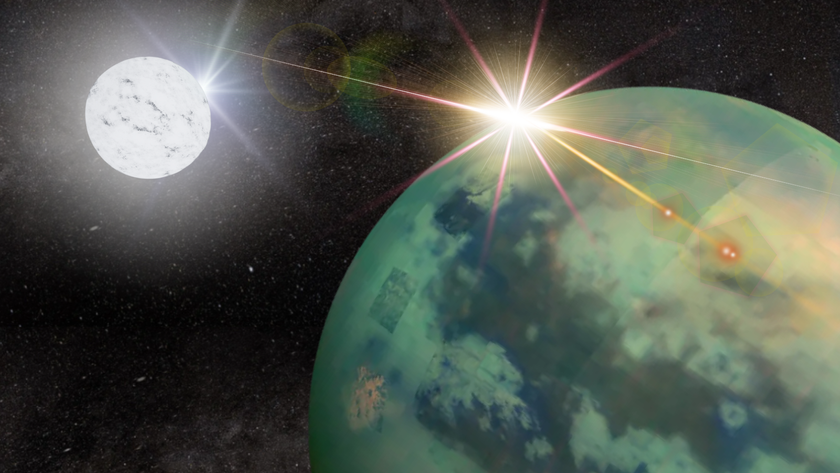

NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope has witnessed an ultradense dead star bending the light of its larger companion, marking one of the first times this phenomenon has been observed in a two-star system.

Kepler detected a large drop in the brightness of a red dwarf star called KOI-256, leading astronomers to believe initially that a Jupiter-size exoplanet had crossed its face.

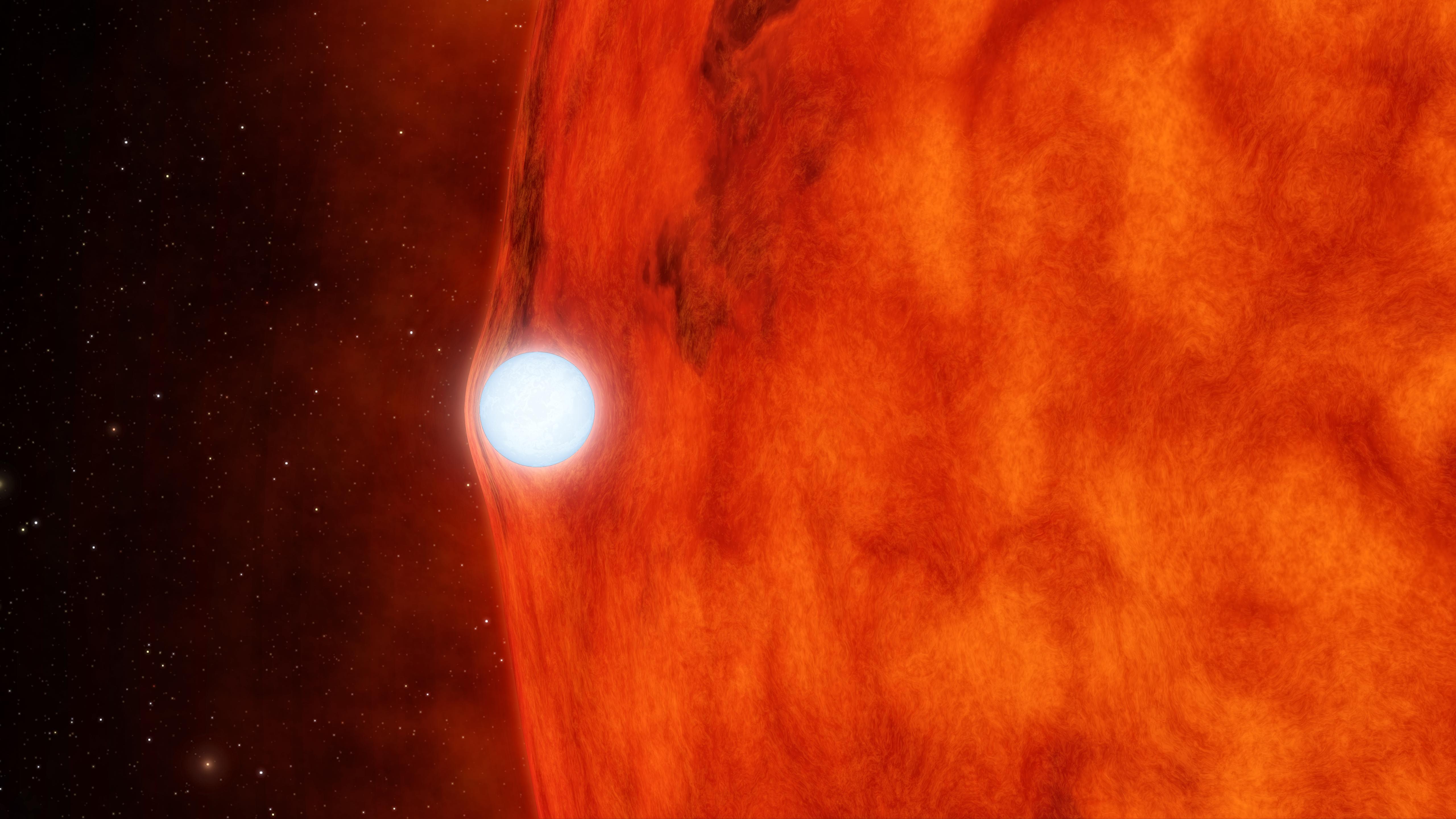

But additional observations by California's Palomar Observatory revealed a wobble in the red dwarf's movements too large to have been caused by the gravitational tug of a planet. The researchers then realized that the brightness dip resulted when a burnt-out stellar core called a white dwarf passed behind the red dwarf, reducing the overall luminosity of the two-star system.

"This white dwarf is about the size of Earth but has the mass of the sun," study lead author Phil Muirhead, of Caltech in Pasadena, said in a statement. "It's so hefty that the red dwarf, though larger in physical size, is circling around the white dwarf." [White Dwarf Bends Companion's Light (Video)]

The researchers then took another look at the Kepler data and found something surprising. The telescope had picked up minuscule brightness fluctuations caused when the white dwarf passed in front of its companion.

The white dwarf's massive gravity was bending the red dwarf's light in a phenomenon known as gravitional lensing, as predicted by Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity.

"Only Kepler could detect this tiny, tiny effect," Doug Hudgins, Kepler program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said in a statement. "But with this detection, we are witnessing Einstein's theory of general relativity at play in a far-flung star system."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers regularly use gravitational lensing to hunt for alien planets and to learn more about dark matter and dark energy, the mysterious stuff that makes up the bulk of the universe.

But in this case, Muirhead and his colleagues employed the phenomenon to calculate the mass of the white dwarf. This information, combined with the data gathered by Kepler and the Palomar Observatory, allowed the team to determine the mass of the red dwarf and the size of both stars, researchers said.

Kepler's main job remains searching for alien planets. The $600 million instrument has detected more than 2,700 potential planets since its March 2009 launch. Only 115 of these candidates have been confirmed by follow-up observations to date, but mission scientists have estimated that more than 90 percent will turn out to be the real deal.

The study will be published April 20 in the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.