NASA Upgrades Historic Giant Vacuum Chamber for Space Telescope

HOUSTON — A giant NASA vacuum test chamber originally built to test the spacecraft that astronauts used to fly to the moon is now ready to check the space agency's next-generation telescope before it launches into deep space.

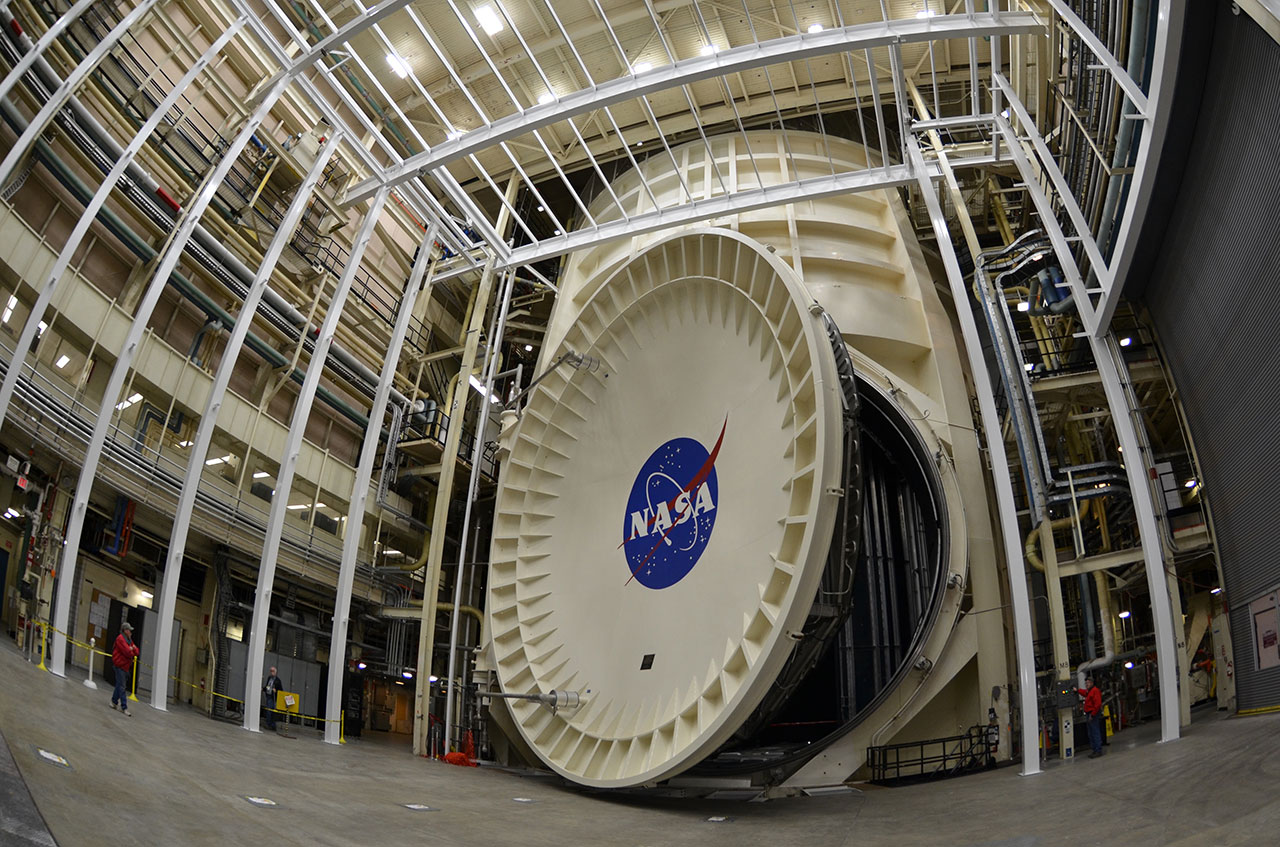

Chamber A located in the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston will begin testing components for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2014, leading up to the tennis-court-size observatory's planned launch four years later.

The largest high-vacuum, cryogenic-optical test chamber in the world, Chamber A has been retrofitted over the past several years to be able to reproduce the extremely-cold environment that the telescope will be exposed to once it enters orbit 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth.

"We are merging the past with the future," Mary Cerimele, NASA's laboratory manager for Chamber A, told reporters during a media tour of the facility Thursday (April 4). "The past is encapsulated in all of the technology and structure surrounding Chamber A and the future, the improvements for James Webb." [Photos: Building the James Webb Space Telescope]

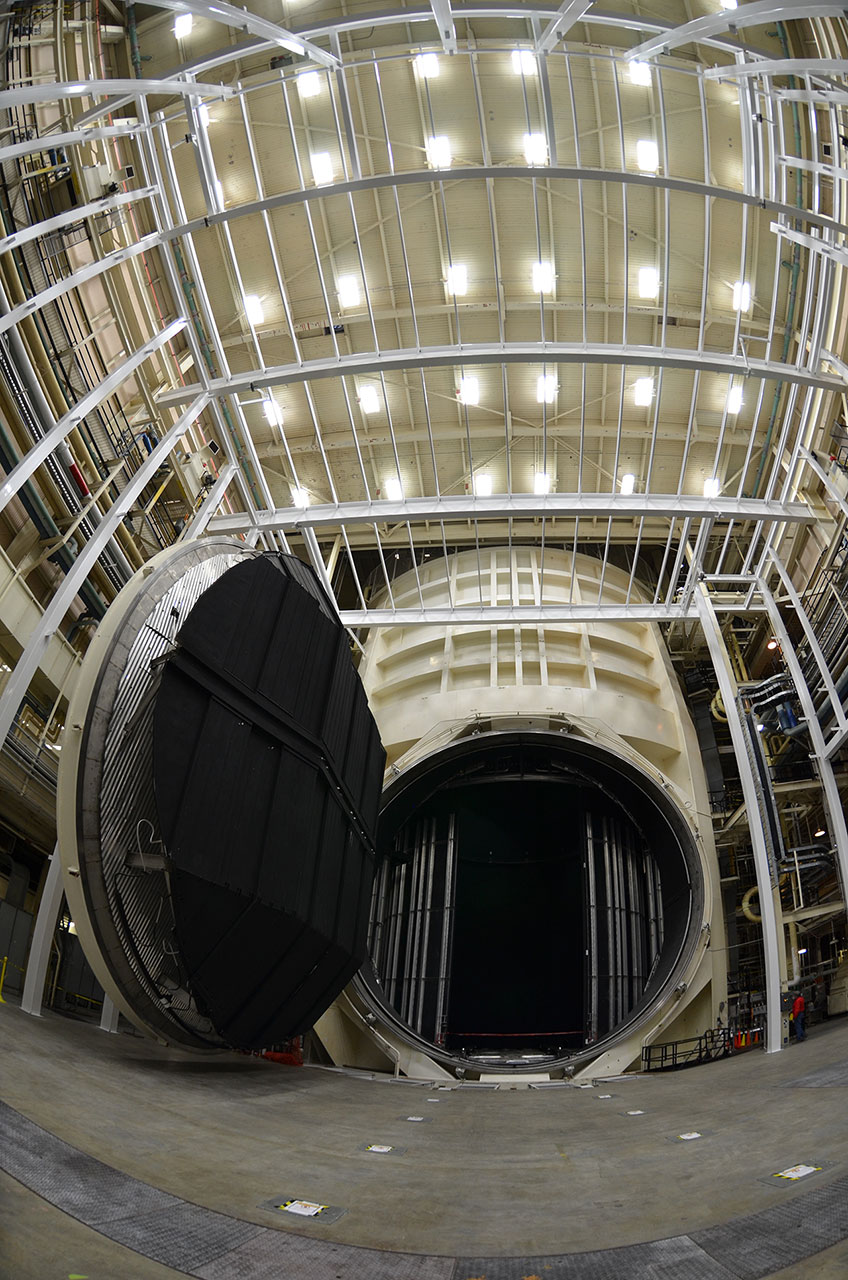

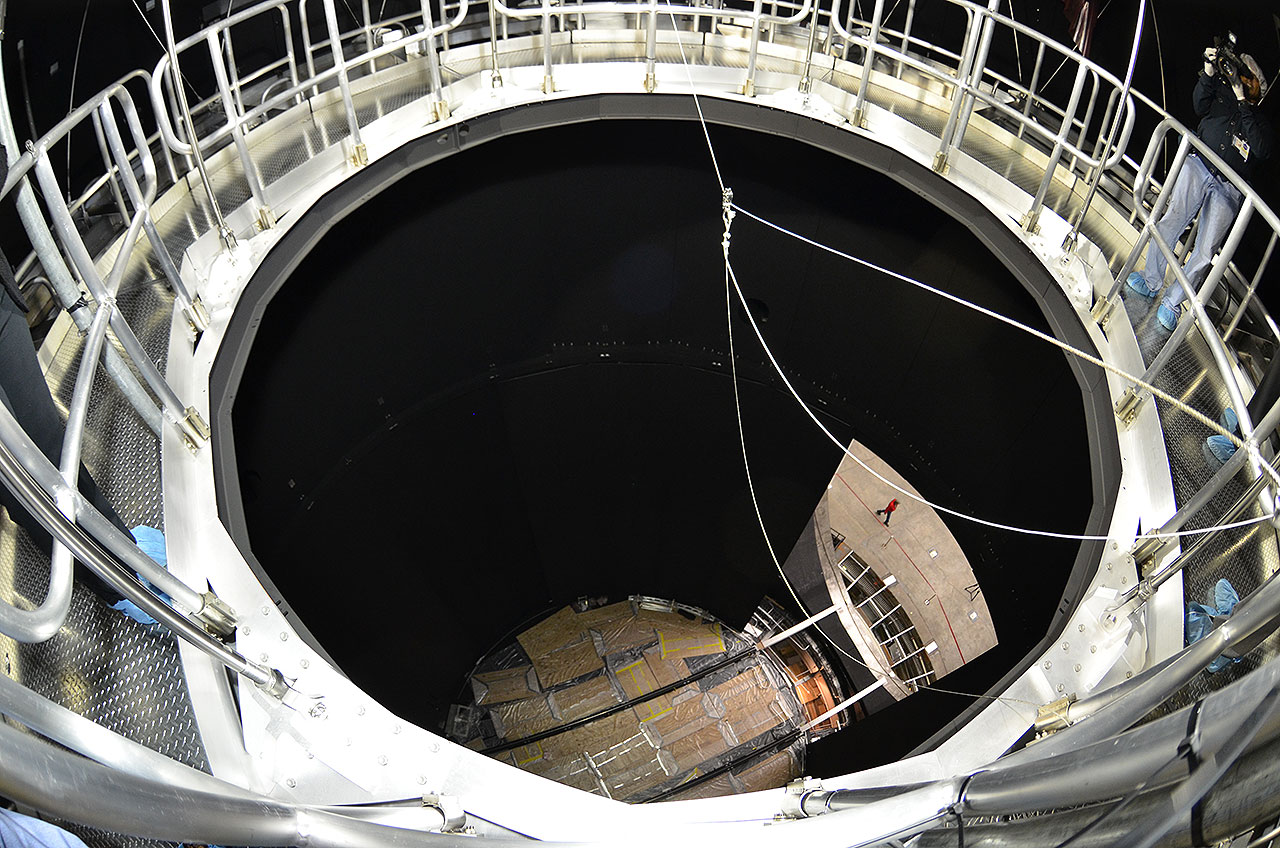

Designed in 1965 to fit the Apollo command and service modules mated together, Chamber A stands 120 feet tall (36.6 meters) and has an exterior diameter of 65 feet (19.8 m). Inside is a volume of 400,000 cubic feet (11,327 cubic meters), which means when its 40-foot (12.2 m), 40 ton door — the largest single-hinged door in the world — is open, there are 50,000 pounds (22,680 kilograms) of air inside.

When at vacuum, Chamber A has, at the most, 0.000033 pounds (15 milligrams) of air remaining.

"The air in the chamber weighs 25 tons, about twelve and a half Volkswagen Beetles," project engineer Ryan Grogan said. "When all the air is removed, the mass left inside will be the equivalent of half of a staple."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Getting colder

If all that was needed to test the James Webb Space Telescope was a near-perfect vacuum, then the years spent modifying Chamber A may have been unnecessary. But to accurately test the observatory's optics, the simulation facility needed to get colder.

The JWST will make observations primarily in the infrared spectrum, but all objects — including telescopes — also emit infrared light. To avoid the telescope's own radiation interfering with it detecting its distant astronomical targets, the observatory and its instruments must be made very, very cold.

To achieve this, the James Webb is equipped with a large shield to block the heating light from the Sun, Earth and moon, and will be positioned at Lagrange Point 2 (L2), the second of five stable orbits in the Sun-Earth system. [Video: How the James Webb Space Telescope Unfolds in Space]

The extremely-low temperatures that the telescope will be exposed to in deep space exceeded what Chamber A was able to support — until now. With its upgraded cryogenics and air flow systems in place, the facility can now achieve a steady internal temperature of 11 Kelvin — 11 degrees above absolute zero — or minus 440 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 262 degrees Celsius).

"It'll be the largest, coldest place on Earth, even in August in Houston," Cerimele said.

One chance to get it right

Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope, which because it is in low Earth orbit was able to be repaired and upgraded by astronauts, the James Webb once launched will be far out of reach.

"We can't service it, so we have to be sure it will work like it is supposed to when it gets to space," Amber Straughn, a deputy project scientist for the Webb Space Telescope at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, told SPACE.com.

Hence the thermal vacuum testing. After working with the telescope's ground support equipment (GSE) over the next couple of years, the JWST's Optical Telescope Element and Integrated Science, or OTIS, will arrive in Houston in 2017 to be installed in Chamber A. The large segment — essentially everything but the tennis-court size sun shield and the engines that will boost the James Webb to L2 — will just clear the chamber's opening by about 6 inches.

The thermal-vacuum testing, which at its longest duration will last about 90 days, will ensure the space telescope's systems operate as expected in the harsh environment of space.

"We need to test something as complicated as the James Webb, with all its different parts and instrumentation, to make sure it works before we launch it, because after we launch it, we're not getting it back," Cerimele said. "It will be four times farther away from us than the moon. We are not going to be able to service it, we are not going to be able to repair it. It has to work when it gets up there, so we do a lot of ground testing."

The $8.8 billion dollar telescope, which will observe distant galaxies to probe for hints and signals left behind from the Big Bang, is slated to launch atop an Ariane 5 rocket from the European Space Agency spaceport in French Guiana. Once its testing is completed in Houston, the OTIS will be flown to California to be integrated with the observatory's other components and then will ship to South America via the Panama Canal.

A clean start

To be ready to receive the James Webb Space Telescope and its components, a clean room is being erected outside Chamber A's entrance, making Thursday's media tour one of the last times that visitors to the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory will have a view of the chamber, a National Historic Landmark since 1985.

In addition to its test of the Apollo spacecraft — including staging the 1968 2TV-1 manned "mission" with astronauts Joseph Kerwin, Joe Engle and Vance Brand inside — the chamber has also tested a number of other space vehicle components.

"Since the 60's, it has been in continuous use for anything that needed to be tested that wasn't really large, such as a space shuttle payload bay door radiator or the radiators for the [International] Space Station, or the Beagle lander for instance, [which] was a European Space Agency project," said Cerimele.

Chamber A was also used to test the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project's docking module, the Skylab space station's telescope mount and antennas for the Department of Defense.

See the collectSPACE.com gallery for more photographs of the historic Chamber A at NASA's Johnson Space Center.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2013 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.