A Second Higgs Boson? Physicists Debate New Particle

DENVER — The discovery of the Higgs boson is real. But physicists are cagey about whether the new particle they've found will fit their predictions or not.

So far, the data suggest that the Higgs, the particle thought to explain how other particles get their mass, is not presenting any surprises, physicists said here today (April 13) at the April meeting of the American Physical Society. But that doesn't mean that it won't in the future — or that there might not be other Higgs bosons lurking out there.

"There's a large number of theoretical models that predict, actually, that this Higgs field is more complicated," said Markus Klute, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Some of these theories predict five or more Higgs bosons of different masses, Klute told reporters. [The Top 5 Implications of Finding the Higgs]

The mystery of the Higgs

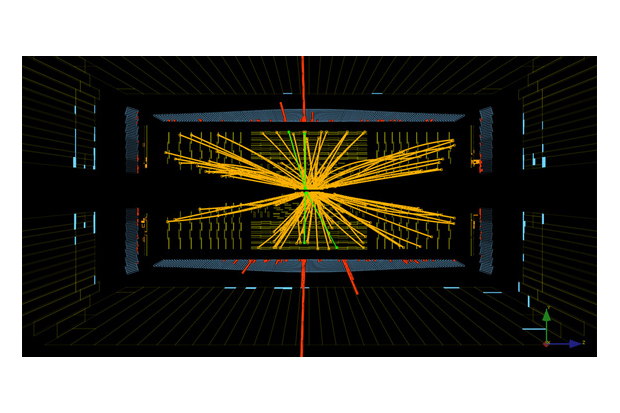

Physicists confirmed in March that a new particle discovered at the world's largest atom smasher, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), is, in fact, the Higgs boson. This particle, which weighs about 126 times the mass of a proton, appears to fit the Standard Model of physics, the dominant theory of particle physics. In this model, the Higgs boson is related to the Higgs field, an energy field that pervades space and is thought to imbue many particles with mass. The thinking goes that just as swimmers would get wet moving through a pool, as particles move through the Higgs field they would gain mass.

This "vanilla" Higgs has been something of a disappointment to physicists hoping to find something that would upend their theories.

"Sometime in November, I was depressed a little bit by the fact that everything lines up so well," Klute said. "They call this 'post-discovery depression.'"

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But researchers say there's more to learn about the Higgs, including whether it's the only one. It's possible that when the Large Hadron Collider revs up again in 2015 with more power, scientists may be able to detect heavier variations of the Higgs boson. Or variations may be hiding in the data collected already.

"As far as 'Is the Higgs standard or not standard,' we're not in the game yet," said Michael Peskin, a physicists at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University. "We will be in the game later this decade, but right now it's just an open question."

A secondary spike in Higgs data presented in December 2012 led to speculation that physicists had perhaps found a second Higgs boson of a different mass. However, that spike showed up in only one LHC experiment. Other lines of evidence produced at the collider have failed to show similar anomalies.

Questions ahead

The 17-mile-long (27 kilometers) underground loop that is the Large Hadron Collider is currently shut down until 2015 as engineers tinker to bring the atom smasher to its fullest potential. Upping the energy levels of the LHC will allow for more collisions, and up to five times the precision in measurements as seen today, Klute said.

One popular theory physicists hope to put to an experimental test is "supersymmetry," which holds that every subatomic particle has a secret twin that has yet to be observed. "Superpartners" could help explain dark matter, a mysterious substance that may makes up a quarter of the entire universe.

So far, physicists can only account for 4 percent of what the universe is made of, said Thomas Koffas, a physicist at Carleton University in Canada.

"The remaining 96 percent," Koffas said, "we have no idea."

This story was provided by LiveScience.com, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.