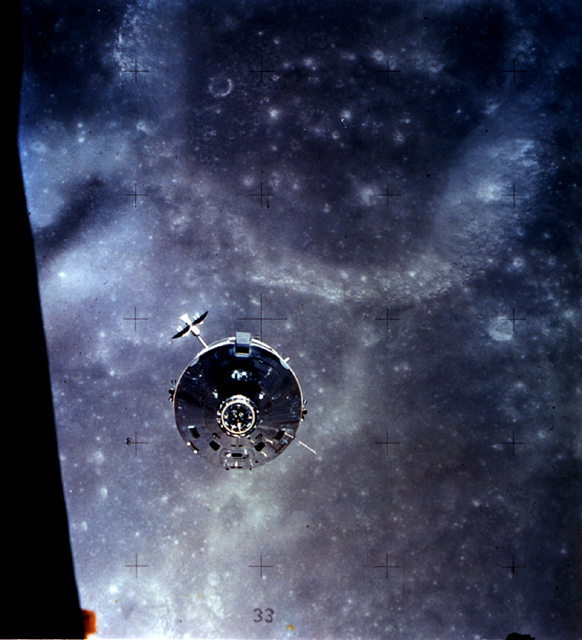

Biography of Ken Mattingly, Apollo 16 astronaut

Mattingly also commanded two space shuttle missions.

Ken Mattingly was a NASA astronaut who flew on the Apollo 16 mission and twice on the space shuttle. He is perhaps best remembered, however, as the astronaut who stayed home from the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission after being exposed to German measles.

In addition to his space missions, Mattingly was an astronaut support crew member for the Apollo 8 and Apollo 11 missions, which both went to the moon, and participated in developing the Apollo spacesuit and backpack that was used on the surface.

Mattingly retired from NASA in 1989 and started working in the private sector. Notably, at Lockheed Martin he was the vice president in charge of developing a space plane called the X-33. The project never made it to the flight stage.

'If this is a practical joke, it's really well done'

Mattingly, a naval astronaut, was an experienced hand in carrier landings. He was deployed with the U.S.S. Saratoga and U.S.S. Franklin D. Roosevelt prior to his selection as an astronaut in 1966.

He entered at a time when Apollo was ramping up quickly. Mattingly served on the support crew for the risky Apollo 8 mission, which was belatedly changed to a lunar orbiting mission when rumors flew that the Russians might get there first. Apollo 8 successfully flew there and returned in December 1968.

Mattingly next assisted with the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission in the same capacity before being assigned to Apollo 14. He and the rest of the crew — Jim Lovell and Fred Haise — were then "bumped up" a mission to Apollo 13 due to training considerations.

Just days before Apollo 13 lifted off in April 1970, Mattingly was exposed to German measles through backup crew member Charles Duke. There were days of medical tests and uncertainty. Mattingly still hadn't heard anything official when he was in his car three days before launch.

"I’m driving up the road, turned the radio on, and they interrupt the news announcement that this afternoon NASA has announced that they have changed and substituted Jack Swigert for me," Mattingly said in a 2001 interview with NASA.

"I just kind of pulled over to the side of the road and sat there for a while. If this is a practical joke, it’s really well done, but I don’t think this is a joke."

It wasn't; the information leaked to the media before Mattingly heard it himself. Mattingly admitted to being disappointed. But, he said, that feeling quickly evaporated when Apollo 13 suffered a devastating explosion in space on April 13, 1970.

Operating a lifeboat

Very quickly, Mattingly — along with the rest of NASA — put every resource possible into bringing the three astronauts home. Backup crewmembers generally had no official assignment during flights, which gave Mattingly a free rein, he recalled: "What I had was a ringside seat that nobody could ever imagine, with the authority to walk into anywhere and listen and kibitz, but I had no particular role."

In the space of a few days, the Apollo 13 astronauts moved into the undamaged lunar module and used it as a lifeboat, reoriented themselves in space to get back home, and built an improvised filter to stop a deadly carbon dioxide buildup in the spacecraft.

As instructions were sent to the spacecraft, Mission Control debated and discussed and calculated what was best. The three men returned safely on April 17, 1970.

Mattingly, who was initially disappointed at missing the flight, had high praise for replacement Jack Swigert's expertise in the command module. He added that Swigert performed better than he ever could have.

"I have a personal thermostat that’s set right around 70 degrees," Mattingly said. "When my body gets below 60 degrees, it doesn’t function. If I had been stuck up there, I would have absolutely been a disaster."

'If I saw too much, I couldn't remember'

Mattingly finally made it to the moon himself on Apollo 16. He performed observations and experiments from orbit while his crewmates, John Young and Charles Duke, did 20-plus hours of exploration on the surface.

"I had this very palpable fear that if I saw too much, I couldn’t remember. It was just so impressive. And these things kept coming for the next 10 days. They never stopped," Mattingly said.

That flight was in 1972. Unlike many of his Apollo counterparts, Mattingly stuck around long after the Apollo program finished and was young enough to be eligible for flights on the next major space vehicle, the space shuttle.

Mattingly's first shuttle flight in 1982 was STS-4, the last test flight of Columbia. Mattingly and crewmate Henry Hartsfield spent seven days in space checking parameters such as Columbia's thermal performance. The men also conducted several science experiments, which included tiny passengers such as fruit flies and algae.

Three years later, Mattingly commanded his last flight: a classified Department of Defense mission, STS-51C. He retired in 1989 and died on Oct. 31, 2023, at the age of 87.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Nov. 2, 2023, with the news of Mattingly's passing.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.