Space Archaeologists Call for Preserving Off-Earth Artifacts

When it comes to preserving history, a group of archaeologists and historians are hoping to boldly go where no archaeologist has gone before.

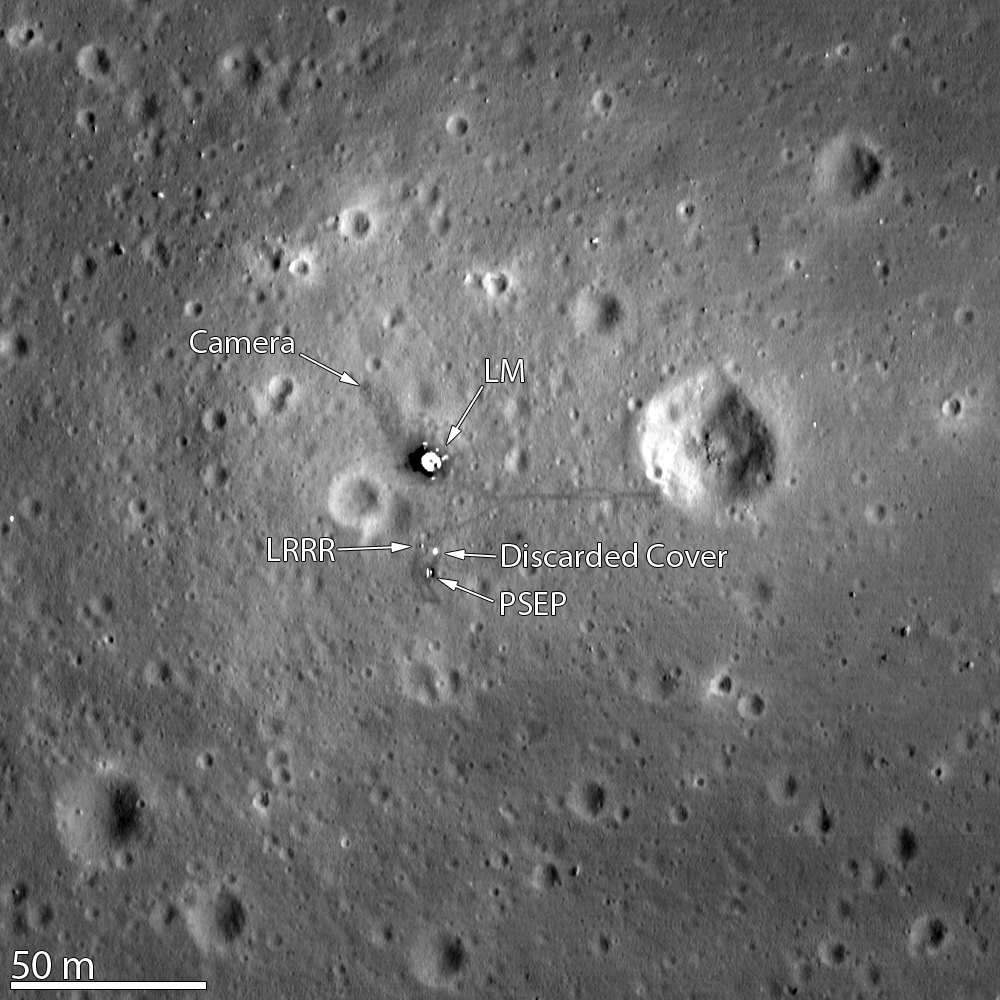

Researchers are increasingly urging humanity to protect off-Earth cultural resources. That may well mean preserving NASA's Apollo landing sites on the moon as national historic landmarks, regarding far-flung spacecraft as mobile artifacts and even working to preserve some pieces of space junk.

"The cultural landscape of space includes both sites and objects on and off Earth," said Beth O'Leary, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of New Mexico in Las Cruces. "It is necessary to evaluate the significance of the latter and treat them as important objects and places worthy of legitimate archaeological inquiry." [Historic Apollo Moon Landers Found! (Photos)]

O'Leary spearheaded a NASA-funded effort to make the 1969 Apollo 11 lunar landing site a national historic landmark. She and other experts in the emerging field of space archaeology gathered at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA), held April 3-7 in Honolulu.

Legitimate archaeological inquiry

O'Leary and Lisa Westwood of California State University, Chico co-chaired the SAA session on space archaeology. The field seeks to scrutinize the routes for preservation of space objects and places.

Westwood said that in 1972 — near the end of the Apollo program — the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted the World Heritage Convention in a pioneering effort to protect universally important monuments, buildings, archaeological sites,and natural and cultural landscapes from being depleted.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"At that time and within that context, cultural heritage was defined by its location relative to then-current political boundaries on Earth. We now can broaden that view to encompass many other historic properties on Earth, on the moon and beyond," Westwood said.

In applying a cultural landscape approach to early space exploration heritage, she asked: Is it possible to designate a World Heritage List district of sites and properties that spans not only multiple countries, but planetary bodies as well?

Historic preservation

"I am a preservationist trying to protect a human archeological site 233,000 miles away," said Joe Reynolds of Clemson University in South Carolina. He detailed his analysis of international space law and how it affects historic preservation.

From 1969 to 1972, NASA's Apollo astronauts completed six separate lunar landing missions, "creating historically significant sites that now sit frozen in the lunar desert," Reynolds said.

Protection of lunar sites is complicated by the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which prohibits countries from exercising territorial sovereignty over the moon or other celestial bodies.

Reynolds reviewed international treaties, such as those governing the ocean floor, Antarctica and the heavens. He also examined the language of the World Heritage Convention, the Geneva Convention, the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, The Antiquities Act of 1906 and various state preservation laws.

"The Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Site can be legally protected," Reynolds said. "What my colleagues and I are trying to accomplish is to legally protect a site of unprecedented human achievement on land that cannot be owned by anyone."

Conserve and protect base camps

According to Reynolds, legal protection of historic or culturally significant sites on land not claimed by any nation is not unprecedented. "There are areas on Earth that share the designation of Res Communis with the moon, such as international waters and the Antarctic continent, and there are a few examples of preservation in those areas," he said.

One example Reynolds cited is the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust. Created in 1987, NZAHT is focused on conserving and protecting the base camps for the four major Antarctic explorations of the early 20th century.

"The Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Site is similar to the camps protected by the NZAHT because at the most basic level, the objects left on the moon are more or less just another base camp, for another historic scientific expedition, on land that cannot be owned by anyone," Reynolds said.

The objects left on the moon by Apollo 11 moonwalkers Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are U.S. government property. Ownership of those objects has never been relinquished.

"This makes the legal protection of these objects a very simple classroom exercise," Reynolds said. "However, getting Congress to agree to it — or anything these days — is another story. One of the reasons for a lack of action to protect this site on the moon may be because it could be construed as a claim of sovereignty on the lunar surface."

Pinnacle of American bravado

Reynolds thinks the Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Site could become a national monument with the stroke of a U.S. president's pen. The Antiquities Act of 1906, he said, gives the president the power to create national monuments via executive order.

Congress could also allow for the protection of the site by passing the Tranquility Base National Historic Landmark Act, written by Reynolds' colleagues Westwood and O'Leary.

The Apollo moon landing sites should be included as national historic landmarks, Reynolds said, because they may represent "the pinnacle of American bravado ... [the] physical manifestation of that innovation, hope and discovery. That is why the U.S. should preserve these sites," he concluded.

Robot avatars

Nearer to planet Earth, Alice Gorman of Flinders University in Australia sees cultural value in orbiting space junk.

There are thousands of defunct satellites, rocket bodies and other pieces of junk currently in Earth orbit. Gorman called this cloud "a robotic colonial frontier" that reflects the nature of our social and political interactions with space and adaptations to a new environment. [Worst Space Debris Events of All Time]

But unlike terrestrial artifacts, orbiting objects are barely visible to us and are not designed to interact with human bodies (with a few notable exceptions, such as the International Space Station)..

"They may represent the beginnings of a technological trajectory that will transform how human cultures relate to time and space," Gorman said.

Representatives of Homo sapiens

In a session at the SAA conference, Peter Capelotti of Penn State University reviewed dead or soon-to-be dead interplanetary spacecraft.

Capelotti noted that space probes navigating the boundaries between our solar system and interstellar space seem to represent "whole new categories of archaeological methodology ... if we are to consider the possibilities of heritage, preservation and, eventually, fieldwork."

For example, NASA's far-flung Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, Voyager 2 and New Horizons probes will "eventually enter interstellar space and become the archaeological representatives of Homo sapiens to the rest of the galaxy," Capelotti said.

Once a spacecraft no longer responds to signals from Earth, it ceases to be used for the original mission for which it was designed, and becomes instead a discarded, and hence, archaeological, object, Capelotti said.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and is co-author of Buzz Aldrin’s new book “Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration” out in May from National Geographic. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.