The mysterious Martian mountain that beckons NASA's Curiosity rover was likely built primarily by wind rather than water, as previously believed, a new study suggests.

Many scientists suspect that the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) Mount Sharp formed primarily from layers of lakebed silt, which is one of the main reasons that the mountain was selected as Curiosity's ultimate destination. But the new study holds that wind probably did most of the heavy lifting.

"Our work doesn't preclude the existence of lakes in Gale Crater, but suggests that the bulk of the material in Mount Sharp was deposited largely by the wind," study co-author Kevin Lewis, of Princeton University, said in a statement. [Latest Mars Photos from Curiosity]

A mysterious mountain

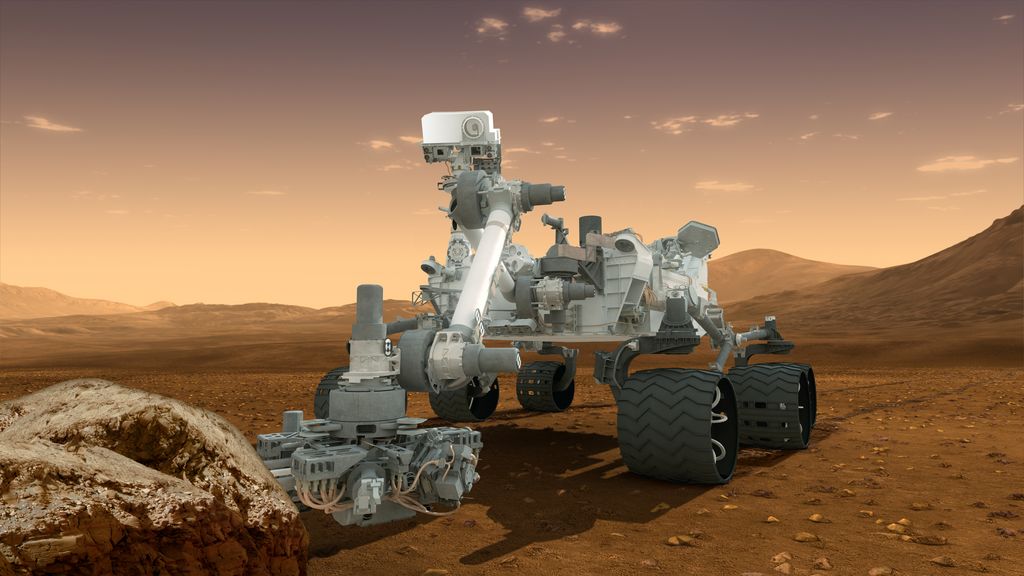

The Curiosity rover landed inside 96-mile-wide (154 km) Gale Crater last August, kicking off a two-year surface mission to investigate Mars' past and present potential to host microbial life.

The 1-ton robot has already checked off its main goal, finding that a spot near its landing site called Yellowknife Bay was once capable of supporting life billions of years ago. But the mission team is still gearing up to send Curiosity on a 6-mile (10 km) trek to the base of Mount Sharp, which was identified before launch as the rover's main science target.

Observations from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) suggest that Mount Sharp's foothills were exposed to liquid water long ago. And as Curiosity climbs up through the mound's many layers, the rover will be able to read the Red Planet's environmental history like a book, mission scientists reasoned.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

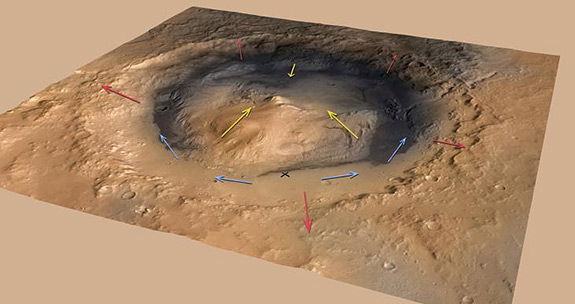

In the new study, researchers used other MRO observations to devise a new theory of Mount Sharp's formation. The team determined that the mound's layers aren't flat-lying stacks, as would be expected in lakebed deposits. Rather, they fan outward in an odd radial pattern from Mount Sharp's center, researchers said.

This finding is consistent with results from the team's computer model, which suggested that wind blowing down Gale's slopes could build a mound in the crater's center while leaving areas near the rim relatively bare.

So Mount Sharp may not be the eroded remnant of an even bigger mound that once filled Gale from rim to rim.

"Every day and night you have these strong winds that flow up and down the steep topographic slopes. It turns out that a mound like this would be a natural thing to form in a crater like Gale," said Lewis, who is a participating scientist on Curiosity's mission. "Contrary to our expectations, Mount Sharp could have essentially formed as a free-standing pile of sediment that never filled the crater."

Testing the theory

Curiosity team member Dawn Sumner, who was not involved in the new study, said it presented interesting ideas that the rover should be able to test out in the future.

"This paper provides a new model for Mount Sharp that makes specific predictions about the characteristics of the rocks within the mountain," Sumner, a geology professor at the University of California-Davis, said in a statement. "Observations by Curiosity at the base of Mount Sharp can test the model by looking for evidence of wind deposition of sediment."

However Mount Sharp formed, the huge Mars mountain should be a productive hunting ground for Curiosity, Lewis said.

"One way or another, we're going to get an incredible history book of all the events going on while that sediment was being deposited," he said. "I think Mount Sharp will still provide an incredible story to read. It just might not have been a lake."

The new study was published in the May issue of the journal Geology.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookor Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.