Will Culture Clash Cloud Hawaiian Telescope? Op-Ed

Christopher Phillips is a science communicator involved internationally with astronomy and space science education, outreach and international development and founded Reach for the Stars - Afghanistan. He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

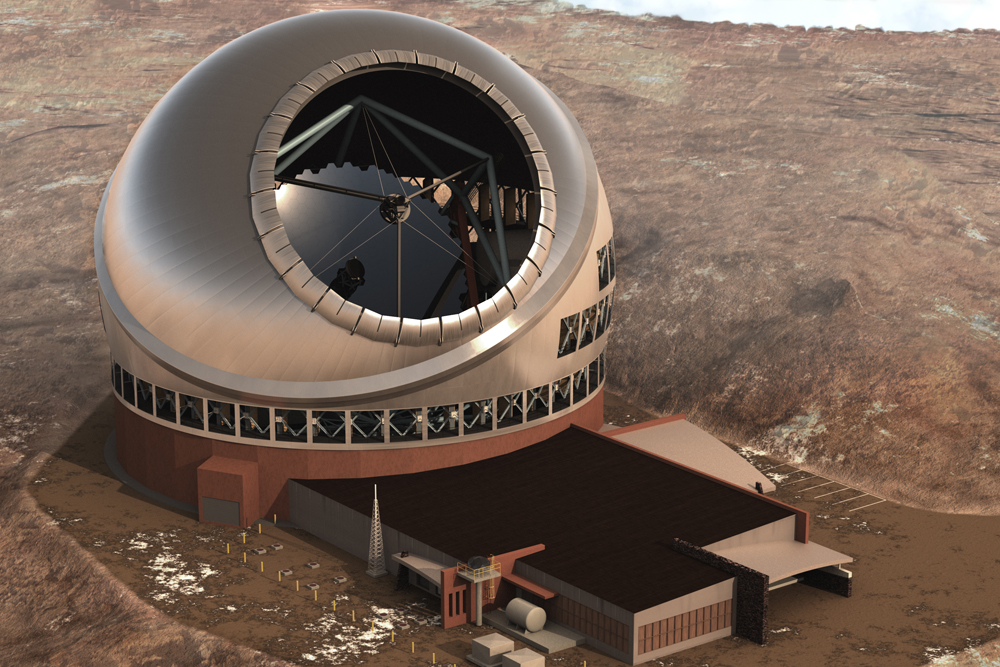

In April 2013, a milestone was reached in the continuing saga of the construction of one of the largest telescopes on Earth, the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). The Hawaiian Board of Land and Natural Resources announced that it had granted a permit that would green-light the construction of the next-generation telescope upon the summit of the extinct volcano of Maunakea.

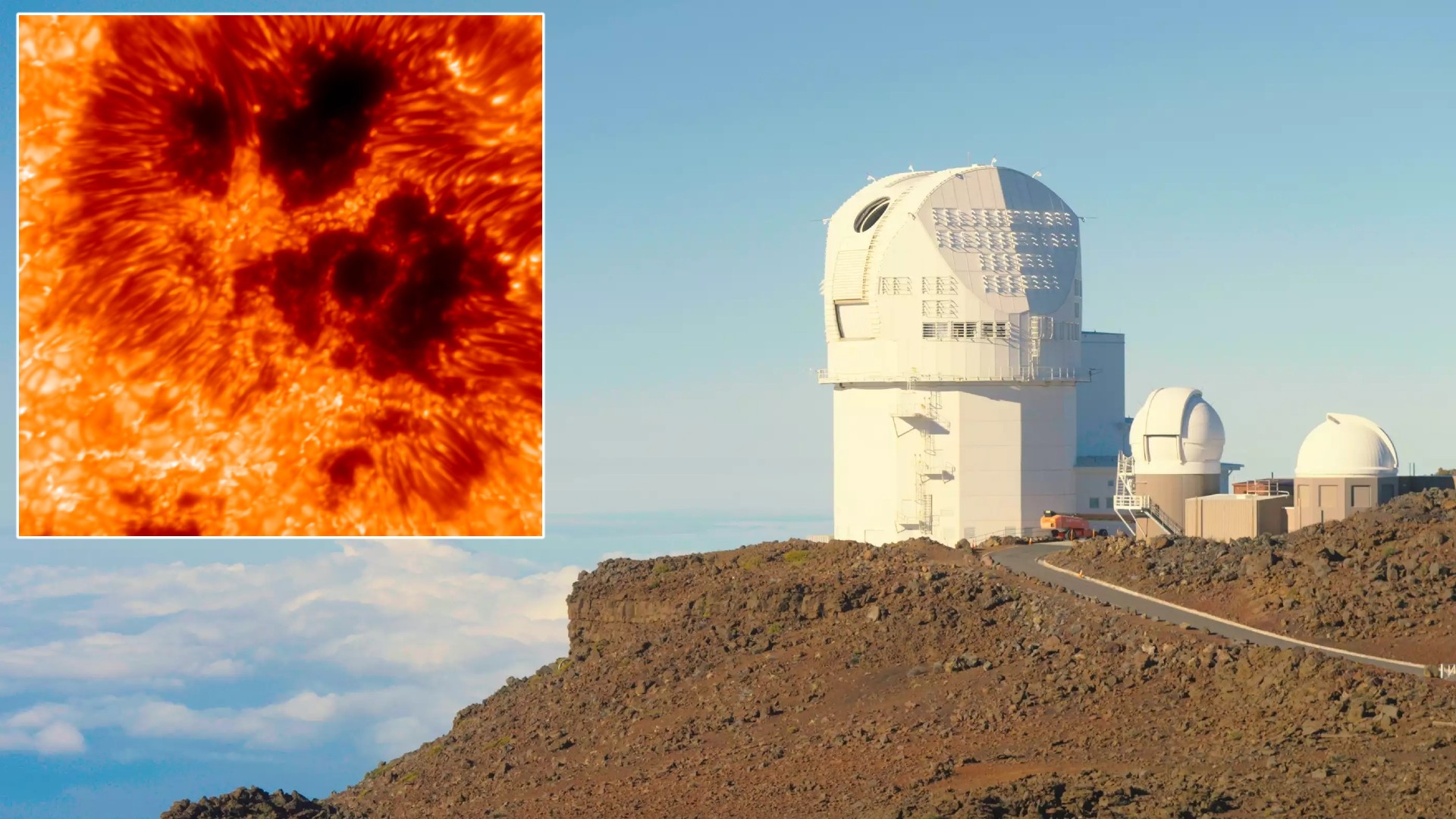

The mountain is currently home to 13 of the world's most scientifically productive observatories, including the Keck telescope with its twin 10-meter observation instruments. Astronomers see the granting of the construction permit as a major victory for a project that, since its conception, has been dogged by controversy — most of which stems from the site choice for the massive instrument.

The TMT will be constructed on what is arguably the single most sacred piece of ground in native Hawaiian culture. A magnificent natural edifice of deep cultural significance, Maunakea represents to native Hawaiians the bond between heaven and Earth, between the realm of the gods and the realm of humanity. It is a "piko," an umbilical connection linking both the domain of Earth and that of the sky. [Hawaii Connects Earth and Sky | Video]

However, this mountain's significance extends beyond the shores of the Hawaiian islands; it has a profound cultural and spiritual resonance to indigenous peoples throughout wider Polynesia. The unmistakable silhouette of this great mountain has been both a navigational and spiritual guide to the generations of Polynesians that have plied the vast ocean between the islands.

The mountain is a link to the heavens not just for the native Hawaiians, but also for the scientific community, including the astronomers that live and work in the Hawaiian islands. So what makes the mountain a prime target for astronomical development in the first place? Why build TMT on the summit of Maunakea?

With its extreme high altitude of 14,000 feet and exquisite visibility conditions, combined with an average of 300 clear observing nights per year, it's no wonder that this incredible observing site was picked. The only other site that currently rivals the mountain of Maunakea for near-perfect observing conditions is in the Southern Hemisphere, the Atacama desert in Chile, site of the European Southern Observatories facilities.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Opposition to the construction of the TMT is based not solely on cultural concerns, however, but also environmental and economic concerns — or lack thereof.

Maunakea is a precious natural resource, a unique and critical habitat to the many species that inhabit the island of Hawai'i. It is home to numerous endemic and endangered species, including birds, plants and insects, and to their respective fragile ecosystems. [48 Species Proposed as 'Endangered,' All Hawaiian]

The mountain also plays a central, but far from understood, role in the water ecology of the island. That hydrology is of vital importance to tens of thousands of human inhabitants residing at its base, residents for whom agriculture is the very basis of the local economy.

With all those vital considerations, there is little surprise that the presence of man-made facilities with their toxic chemicals, human waste and history of environmental mismanagement is causing controversy. It doesn't help when this entire scenario is transposed against a history of colonialism and exploitation in the Hawaiian islands.

The TMT represents a clash of science and society, the past and the future — but, more than that, it's a modern example of the cost of scientific progress. How far are we willing to go in the name of development, and what are we willing to sacrifice in our pursuit of knowledge?

The astronomical community and its followers are not used to such controversy in the field. Historically, astronomy has been referred to as "the noble science," unmarred by the public controversies that surround other disciplines such as the biosciences with its big pharma, stem cell research, animal testing and ethically questionable practices such as the development of chemical and biological weapons. Astronomy and space science, on the other hand, have maintained a relatively clean image in the public eye. However, in the 21st century, science is an industry and astronomy is big business, and just like all big businesses there are interests to be served, palms to be greased and money to be made. The profits of the scientific enterprise can be measured not only in gains in knowledge, but also in the currency of capitalism.

TMT's pundits have touted that the construction of this world-class facility will bring jobs and other economic benefits to the people of Hawai'i, a siren song that is often heard during large development projects, particularly in the developing world.

The concern is: just how much of those economic benefits, if any, will trickle down to the local people of the island of Hawai'i? History teaches us that rarely do local communities fully benefit from such projects, no matter the great intention. Contractors, academic institutions and special interest groups, however, stand to be financially better-off during projects of such great undertaking. Whether they are considered an intrinsic part of the local economy is a point of some contention.

So what is left after the lions share? Take a walk around downtown Hilo and it would appear that very little of the billions of dollars invested in the mountain have made it to sea level. What's even more shocking is that despite previous education and outreach efforts by the astronomical community, you can walk into any local school and find the children there have no idea that some of the most profound discoveries in the history of the human race are taking place on their island, let alone roughly an hour's drive away.

Sadly, the state of education in Hawai'i leaves much to be desired in comparison to the rest of the United States. One thing that is sorely needed is sustained investment in the local economy by the scientific community; piecemeal outreach efforts by the observatories just will not cut it. It is understandable, then, that there is resentment toward the astronomical community, people deemed to be residing in their ivory towers whilst the children of Hawai'i island struggle through an underfunded and dysfunctional education system. [States Ranked Best to Worst on Science Education]

Should the astronomical community shoulder the burden of helping to fund the infrastructure of the Hawaiian islands? No, of course not, it is entirely unrealistic to expect such a thing — that responsibility falls to the state and federal legislatures.

One thing the astronomical community can contribute to the island of Hawai'i is a more active education and outreach program: they can engage more with local community figures and interest groups to better represent the cause of science; they can fight alongside local groups to press for more investment in education and jobs; and they can fix the broken science communication apparatus. In short, despite recent budget cuts, if Costco-warehouse-size facilities are going to be constructed upon this contentious ground, the astronomical community can and must do more for the local community it is supposed to serve.

This story was provided by LiveScience.com, a sister site to SPACE.com. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This article was originally published on LiveScience.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.