Mystery of Moon's Magnetic Field Deepens

The moon generated a surprisingly intense magnetic field until at least 3.56 billion years ago, 160 million years longer than previously thought, a new study reports.

These findings could shed light not just on the magnetic field of the moon, which is now extremely weak, but on that of asteroids and other distant worlds, investigators added.

Earth's magnetic field is created by its internal dynamo, which itself is generated by the planet's churning molten metal core. Research increasingly suggests that the moon once had a dynamo as well, with evidence of magnetism found in lunar rocks returned by Apollo astronauts. [10 Surprising Moon Facts]

Models of the moon's core suggest its dynamo should have lasted only until about 4.1 billion years ago. However, last year, scientists revealed that the moon possessed a magnetic field for much longer than previously thought, with a powerful dynamo in its core from 4.2 billion years ago to at least 3.72 billion years ago.

Researchers have proposed two possibilities to explain why the moon's dynamo lasted so long. One possible explanation is that giant cosmic impacts set the moon lurching enough to drive its dynamo. Another explanation has to do with how the moon's core spins around a slightly different axis than its surrounding mantle layer, generating wobbles — known as precession — that could dramatically stir its core.

The cosmic-impact idea is supported by the fact that the moon experienced massive collisions until around 3.7 billion years ago, such as the one that created the 715-mile-wide (1,150 kilometers) Mare Imbrium, among other craters.

However, the dynamo generated by each impact would have lasted for a mere 10,000 years or so, scientists say. In contrast, if precession drove a lunar dynamo, the moon could have continuously possessed a magnetic field until as late as 1.8 billion years ago.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

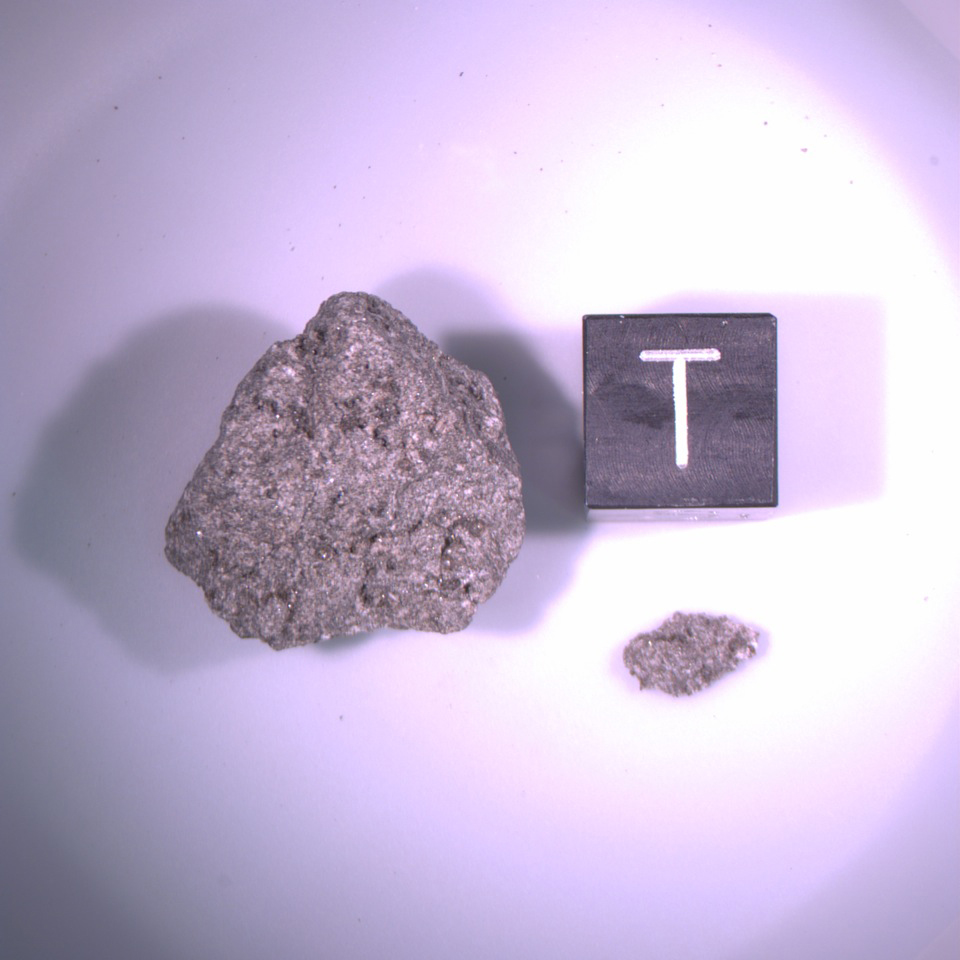

Now, a new analysis of the biggest lunar rock brought back to Earth by Apollo 11 astronauts in 1969 reveals the moon's dynamo lasted about 160 million years longer than previously thought, well after the last of the largest crater-forming impacts hit the moon.

Scientists investigated a 5-gram (0.18 ounces) sample taken from a 3.56-billion-year-old volcanic moon rock from the Sea of Tranquility.

"When rocks solidify from a lava, they capture a record of the magnetic field in their environment," said study lead author Clément Suavet, a geoscientist at MIT. "By studying rocks of different ages, we can reconstruct the history of lunar-surface magnetic fields."

The analysis revealed the intensity of the lunar magnetic field was exceptionally strong 3.56 billion years ago, "almost identical to the field measured in a previous study of 3.7-billion-year-old rocks," Suavet told SPACE.com. "This seems to indicate that the lunar magnetic field was remarkably stable."

The ancient magnetic field of the moon was about as intense as Earth's current surface magnetic field. This makes it about 1,000 times stronger than the moon's present surface magnetic field, researchers said.

"The moon is like a giant laboratory where we can test our theories about how planets form and evolve," Suavet said.

Many questions remain about the moon's magnetic field, such as why it was so intense late into lunar history and how it disappeared over time.

"The question is, when and how did the dynamo decay?" Suavet said.

The scientists detailed their findings online May 6 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookor Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us