How the Mighty Winds of Uranus and Neptune Blow

The powerful winds of Uranus and Neptune are apparently confined to tight layers in both planets, researchers have determined.

These findings could shed light on how those immensely strong winds are born, and how giant planets form and evolve over time, scientists added.

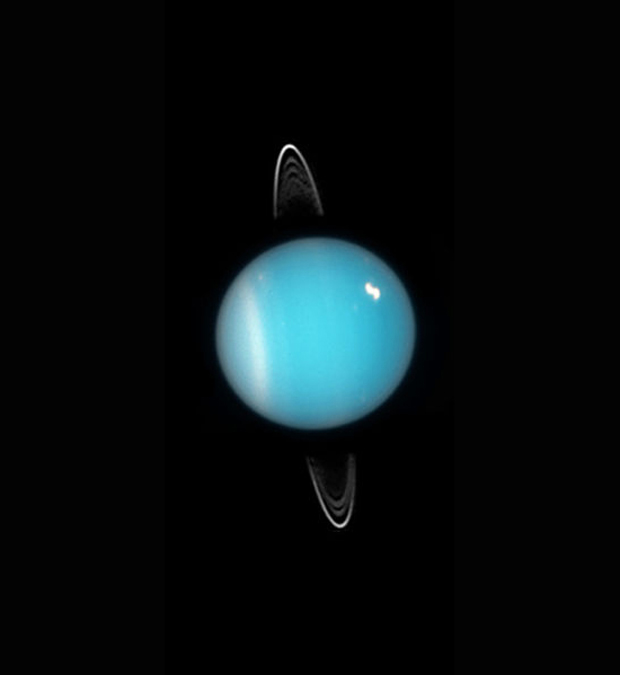

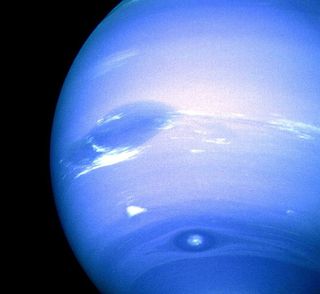

Giant planets in the outer solar system, like Uranus and Neptune, are dominated by winds that can reach supersonic speeds and jet streams 10 to 15 times stronger than those found on Earth, judging by images of how clouds race by on those worlds. However, just how deep those winds reached was unknown until now, hidden as those lower depths are beneath those dense layers of clouds. [Photos of Uranus from near and far]

"This has been an open question for the last 25 years," study lead author Yohai Kaspi, a planetary scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, told SPACE.com.

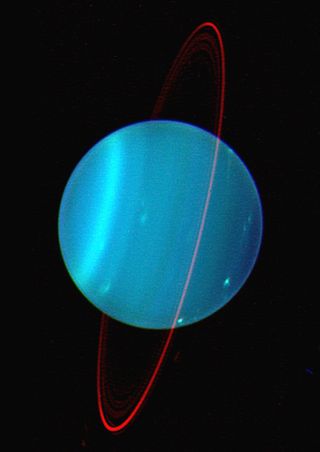

Kaspi and his colleagues focused on Uranus and Neptune, which are both "ice giants" — massive planets with icy atmospheres. The winds of Uranus can blow clouds up to 560 miles per hour (900 kilometers per hour), while Neptune's winds can reach up to 1,500 miles per hour (2,400 kilometers per hour), the fastest planetary winds detected yet in the solar system.

The researchers investigated the gravity fields of those worlds using data gathered by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft and ground-based telescopes. The strength of a planet's gravity field depends on its amount of mass, and this strength can vary over the surface of a planet depending on the amount of mass lying under it. By analyzing the gravity fields of these worlds, the investigators could deduce how their atmospheres circulated.

The scientists discovered the winds blow in relatively thin weather layers no more than 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) deep on both planets. For comparison, Neptune is about 30,600 miles (49,250 km) in diameter, while Uranus is approximately 31,500 miles (50,700 km) wide.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These findings help reveal how these winds originate, researchers said.

Past studies have suggested the winds on Uranus and Neptune might arise one of two ways — either shallow processes in their outer atmospheres, or deeper atmospheric mechanisms extending into their interiors. The researchers found the windy layers of Uranus and Neptune occupy the outermost 0.15 and 0.2 percent of their masses, respectively, suggesting that shallow processes drive those winds, such as swirling caused by moisture condensing and evaporating in the atmosphere.

The new study has implications for how scientists understand how planets form.

"When it comes to thinking about the effects of dynamics on planetary formation, we're saying the bottom 90 percent of giant planets is static," Kaspi said.

In the future, the Cassini spacecraft currently orbiting Saturn and NASA's Juno probe that is scheduled to reach Jupiter can analyze the gravity fields of those giant planets and help better explain their winds as well.

"The four giant planets have more than 99 percent of the mass of the solar system outside the sun, and within the next few years, we're going to be learning about the dynamics of all of their atmospheres," Kaspi said. Saturn and Jupiter should be more complicated to analyze than Uranus and Neptune because the former two planets have more jet streams than the latter pair, Kaspi said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the May 16 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us