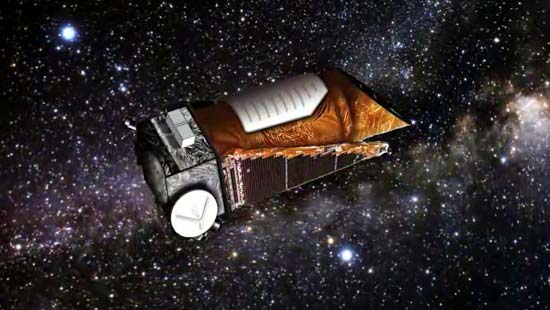

There's a chance that NASA's Kepler space telescope can recover from the malfunction that has halted its wildly successful search for alien planets, mission team members say.

The second of Kepler's four reaction wheels — devices that allow the observatory to maintain its position in space — has failed, depriving Kepler of the ability to lock precisely onto its 150,000-plus target stars, NASA oficials announced Wednesday (May 15).

But mission engineers are not conceding that Kepler's planet-hunting days have come to an end, vowing to try their best to recover the failed reaction wheels over the coming weeks. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

"I wouldn't call Kepler down and out just yet," NASA science chief John Grunsfeld told reporters Wednesday.

Balky reaction wheels

The Kepler spacecraft spots exoplanets by detecting the tiny brightness dips caused when they pass in front of their parent stars from the instrument's perspective.

The observatory needs three working reaction wheels to do such precision work. When Kepler launched in March 2009, it had four — three for immediate use and one spare.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One of the wheels, known as number two, failed in July 2012, giving Kepler no margin for error. And the loss this week of another one (called number four) puts an end to the spacecraft's exoplanet hunt, unless a fix can be found.

Engineers have begun considering strategies for bringing the wheels back into service. They'll likely try a light touch at times and a brute-force approach at others, officials said.

"Like with any stuck wheel that you might be familiar with on the ground, we can try jiggling it," said Kepler deputy project manager Charlie Sobeck, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif. "We can try commanding it back and forth in both directions. We can try forcing it through whatever the resistance is that's holding it up."

It's also possible that wheel number two will spring back to life if turned on again now, rested and restored after its long break, Sobeck and others say.

"It was putting metal on metal, and the friction was interfering with its operation, so you could see if the lubricant that is in there, having sat quietly, has redistributed itself, and maybe it will work," Scott Hubbard of Stanford University said in a statement. (Hubbard served as director of NASA Ames during much of Kepler's development and helped guide the mission.)

It will take a few weeks to put together a recovery plan, Sobeck said. It's unknown if any potential fixes will do the trick, but Kepler team members are keeping their fingers crossed.

"There is a reasonable possibility that we will be able to mitigate that problem," said mission principal investigator Bill Borucki, also of NASA Ames. "So I don't think I'd be a pessimist here."

There's no chance of sending astronauts out to service Kepler, as was done five times with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope over the years. Kepler orbits the sun rather than the Earth, and it's currently about 40 million miles (64 million kilometers) from our planet.

Another mission?

Kepler has already outlasted its prime mission life of 3.5 years. And even if both reaction wheels are beyond help, Kepler's science work may not come to an end.

It's possible Kepler could still gather valuable data by switching to a scanning mode, as opposed to the "point and stare" operations that defined its first four years in space. If neither failed reaction wheel is recovered, NASA will carry out studies addressing possible new missions for Kepler.

It's too soon to speculate what such missions might look like, officials said.

"We need to know more about the performance of the spacecraft before we can assess what kind of science we'll be able to do with that performance," Sobeck said.

More discoveries to come

Kepler has spotted more than 2,700 potential exoplanets to date. Just 132 of them have been confirmed by follow-up observations so far, but mission scientists expect that more than 90 percent will end up being the real deal.

And the flood of Kepler finds won't slow for a while even if the instrument can no longer lock onto its target stars. The mission team has only had time to go through about half of Kepler's enormous dataset, which team members say is certain to contain many more gems — including, possibly, the first-ever "alien Earth."

"We have excellent data for an additional two years," Borucki said. "So I think the most interesting, exciting discoveries are coming in the next two years. The mission is not over."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.