The stars will align for planet hunters twice in the next three years, allowing them to probe the nearest star to our own solar system for Earth-size alien worlds.

Proxima Centauri, which lies just 4.24 light-years from Earth, will pass in front of background stars in both October 2014 and February 2016. Astronomers should scrutinize Proxima during these two periods, looking for subtle light shifts that could reveal the presence of close-orbiting planets, a new study reports.

"This is an opportunity to determine the mass of Proxima, and also detect planets up to 4 AU [astronomical units] around Proxima Centauri," Kailash Sahu, an astronomer with the Space Science Telescope Institute in Baltimore, Md., told reporters today (June 3) at the 222nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Indianapolis. [Alpha Centauri Star System Explained (Infographic)]

One astronomical unit is the distance from Earth to the sun, or about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

The closest alien planets?

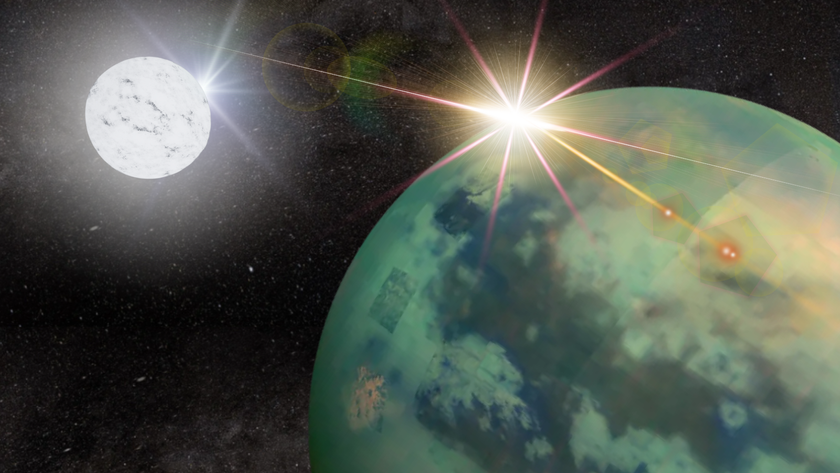

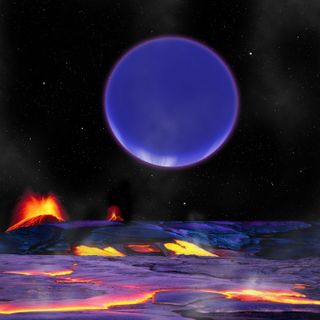

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf, meaning it's cooler and smaller than our own sun.

Red dwarfs are the most common stars in the Milky Way, making up about 75 percent of the galaxy's stellar population. They're good candidates to host rocky, roughly Earth-size worlds, since lower-mass stars tend to have relatively smaller planets, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Proxima is part of the three-star Alpha Centauri system, the closest solar system to our own. A scorching-hot rocky exoplanet roughly the size of Earth was discovered circling Alpha Centauri B, another star in the system, last year.

Astronomers have yet to find any worlds circling Proxima, but they continue to look. And the upcoming star alignments — which Sahu and his colleagues predicted by plotting Proxima's path through the heavens using data from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope — give them a rare chance to ramp up the search.

The alignments offer an opportunity to take advantage of a phenomenon called gravitational microlensing. As Proxima passes in front of the two background stars, its gravitational field will bend and magnify the distant stars' light, acting like a lens.

This process produces a light curve — a brightening and fading of the faraway stars' light over time — whose characteristics will tell astronomers a lot about Proxima. For example, researchers should be able to nail down Proxima's mass with unprecedented precision, which will in turn shed light on its temperature, diameter, brightness and longevity.

Any planets orbiting within 4 AU of Proxima Centauri should also generate a noticeable blip in the light curve during the October 2014 and February 2016 events, Sahu said. (For reference, Jupiter's average orbital distance from the sun is 5.2 AU.)

"If the planet happens to pass close to the star, it's possible to detect," Sahu said.

Getting the word out

Hubble would be able to pick up a planetary signature in the light curve, Sahu added, as would several other powerful instruments, such as the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile.

Sahu and his team hope their new study, which has been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal, will get the word out, helping catalyze a full-on planet hunt using such big and capable telescopes.

"This is a rare opportunity where people can, in principle, look for planets around Proxima Centauri," Sahu said. "Hopefully this will lead to such a campaign."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.