'Mini-Neptune' Alien Planets in Star Cluster Surprise Scientists

Alien planets are popping up in unexpected places.

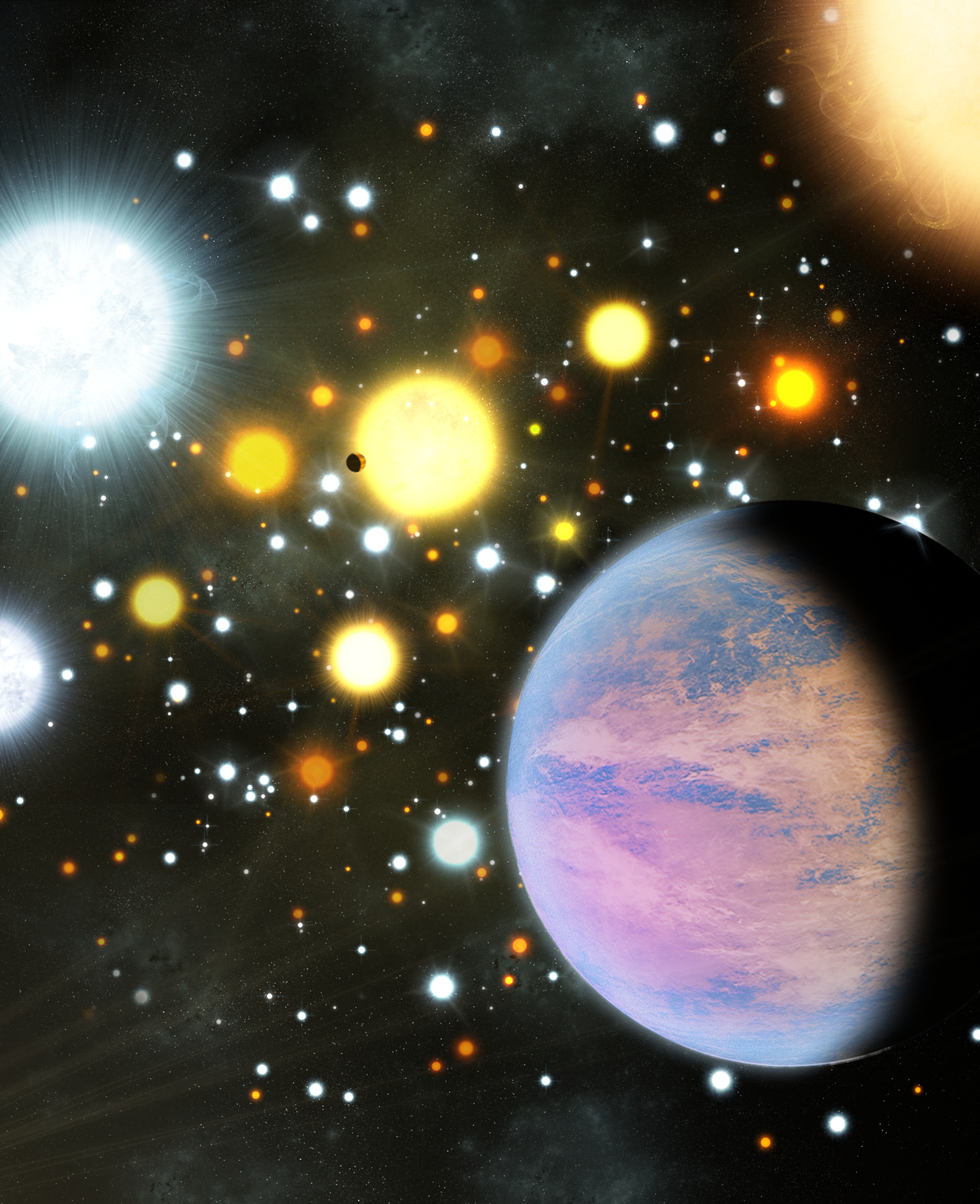

Astronomers using the planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft have found two planets circling different stars in the violent environment of an ancient open star cluster called NGC 6811 located about 3,300 light-years from Earth. Until now, four of the more than 850 planets known outside the solar system were spotted in clusters.

The planets — Kepler-66b and Kepler-67b — are both smaller than the planets previously found in clusters. They are slightly smaller than Neptune, but larger than the Earth and circle sunlike stars. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

"We don't have any planet that falls in that size bin or that mass bin between the Earth and Neptune, so we have to try to speculate about how they might be, structurally speaking," lead study author Soren Meibom, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said. "It's unlikely that they're completely solid like the Earth because there is no precedence for that. If you have a planet this size, three-quarters the size of Neptune, about three Earth radii, it's very likely to have a gaseous envelope, so it's kind of in between a rocky planet like a Neptune … but we don't have any analogue in the solar system, so we're left guessing a little bit."

The new research is detailed in the June 27 issue of the journal Nature.

Forming in a cluster

Some scientists thought that it would be more difficult for exoplanets to survive in star clusters because of the turbulent environment that surrounds them. Supernova explosions and the movements of other stars in the cluster can change the orbits of planets that formed around relatively stable stars. [How Alien Planet Sizes Stack Up (Infographic)]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The orbits of Kepler-66b and Kepler-67b, however, do not seem to have been disturbed since their formation one billion years ago, Meibom said.

These planets are also unique because they are the first cluster-based planets to be discovered by transiting — passing between their star and the Earth. This allowed Meibom to measure their relatively small size.

"Big planets are easier to find, but if they are less common than small ones, we may not find them," William Welsh, an astronomer at San Diego State University who is unaffiliated with the research, said. "Previous searches for transiting planets in clusters didn't find any planets, but it's not because planets are rare. It's because 1) planets as small as the ones in this paper are extremely hard, if not impossible, to detect using a ground-based telescope; and (2) the large Jupiter-size planets that could have been found are less common than the harder-to-see and more common small planets."

Just as common

Meibom and his team used data they collected from 377 stars in the cluster to understand the frequency of finding cluster-based planets versus planets circling stars in the open field. They found that astronomers can expect to detect a similar number of mini-Neptunes in both the field and in clusters.

These types of planets could be just as commonly found orbiting stars in clusters as they are around other kinds of stars.

"The two planets we found are going around their stars over a time of 15 and 17 days respectively and that is also a very typical orbital period for planets found outside of clusters," Meibom said. "Both the frequency and the properties in terms of size and orbital period are consistent with what we see outside of clusters."

This finding might also help scientists understand whether habitable alien planets could form in clusters, however, it is still unclear whether life could exist while a young star remains within a cluster.

"The sun was once part of a cluster, and our solar system planets formed while part of the cluster," Welsh wrote in an email to SPACE.com. "Life probably did not emerge while the sun was part of the cluster, though that depends on how long it took for the cluster to dissolve. But the reason for that may be more due to the bombardment of the very young Earth by proto-planetary debris than anything to do with the cluster environment … Life probably did not get a permanent foot-hold on Earth while we were part of a cluster, if the cluster dispersed in less than 700 million years."

Future missions

It could also be possible to search for planets in closer star clusters like the Pleiades or the Hyades, but it might not happen for a while, Meibom said. Kepler cannot hunt for planets in those closer clusters because it is focused on only one part of the distant sky, and ground-based methods have not been powerful enough to detect any small planets as of yet.

Future missions, however, could help scientists investigate these closer clusters, Meibom said. NASA's planned Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, launching in 2017, will search for planets transiting in front of smaller and cooler stars — the most common in the galaxy.

This is the second bit of surprising exoplanet news in as many days. Scientists recently found three planets within the habitable zone of a star 22 light-years from Earth.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter and Google+. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.