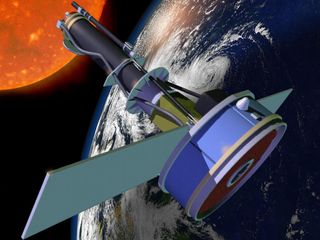

NASA's newest solar observatory launched into space late Thursday (June 27), beginning a two-year quest to probe some of the sun's biggest mysteries.

An Orbital Sciences Corp. Pegasus XL rocket and the new solar telescope — called the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph satellite, or IRIS — left California's Vandenberg Air Force Base underneath a specially modified aircraft at 9:30 p.m. EDT Thursday (6:30 p.m. local time; 0130 GMT Friday).

Nearly one hour later, at 10:27 p.m. EDT (7:27 p.m. local time), the plane dropped its payload 39,000 feet (11,900 meters) above the Pacific Ocean, about 100 miles (160 kilometers) northwest of Vandenberg. After a five-second freefall, the Pegasus rocket roared to life and carried the sun-watching IRIS into Earth orbit. [NASA's IRIS Solar Observatory Mission in Pictures]

"We're thrilled. We're very excited," NASA launch director Tim Dunn said just after the successful blastoff. "We've gotten good data back. The solar arrays did begin to deploy and everything is proceeding right on track."

Scientists hope IRIS' observations help them better understand how energy and material move around the sun. They want to know, for example, why the outer atmosphere of the sun is more than 1,000 times hotter than the star's surface.

Solar mysteries

IRIS is part of NASA's Small Explorer program, which caps the cost of a space mission at $120 million. Like its budget, the spacecraft is small, weighing just 400 pounds (181 kilograms) and measuring 7 by 12 feet (2.1 by 3.7 m) with its power-generating solar panels deployed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

After a 60-day checkout period on orbit, IRIS will begin its science campaign. The probe will stare at a mysterious sliver of the sun between the solar surface and its outer atmosphere, or corona.

Researchers hope a better understanding of this interface region, which is just 3,000 to 6,000 miles (4,800 to 9,600 kilometers) wide, helps explain why temperatures jump from 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius) at the sun's surface to 1.8 million degrees F (1 million degrees C) or so in the corona.

"What causes this rise? How does the energy transfer from the surface, the cool surface, to this hot outer atmosphere?" Jeffrey Newmark, IRIS program scientist at NASA Heaquarters in Washington, D.C., said Tuesday (June 25) during a prelaunch mission briefing. "These are the questions that IRIS, the science of IRIS, is going to address."

A more focused look at the sun

While other NASA solar spacecraft — such as the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) and the two STEREO (Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory) probes — record views of the entire sun, IRIS' spectrograph will focus on just 1 percent of our star at a time, resolving features as little as 150 miles (240 km) across.

IRIS' relatively narrow view should complement other solar probes' broader look nicely, mission scientists said.

"Relating observations from IRIS to other solar observatories will open the door for crucial research into basic, unanswered questions about the corona," Joe Davila, IRIS project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement.

IRIS was orginally slated to launch Wednesday (June 26), but a power outage across California's central coast knocked out key elements of Vandenberg's tracking and telemetry systems, causing a one-day delay.

Powerful sun storms can wreak havoc with electrical grids here on Earth. So the delay was appropriate in a way, highlighting the importance of IRIS' mission, said Pete Worden, director of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., which is responsible for IRIS mission operations and ground data systems.

"The better we can understand the physics going on, the better we can understand the [solar] activity, the better that we can potentially predict and mitigate some of these problems," Worden said Tuesday.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.