Comet ISON: A Timeline of This Year's Sungrazing Spectacle

The sungrazing Comet ISON could put on a dazzling display when it slingshots around Earth's star this November.

If the icy dust ball doesn't get ripped apart by extreme solar forces, some astronomers have said it could be the "comet of the century," possibly shining brightly enough to be seen during the daytime.

ISON began its dangerous journey toward the inner solar system about 10,000 years ago, when it left a distant band of icy space rocks in the Oort cloud. But scientists and skywatchers only became aware of ISON last year. Here's a look at what scientists have learned about the comet since then, and what to expect in the months and days ahead. [Photos of Comet ISON: A Potentially Great Comet]

September 2012: Discovery

The discovery of Comet ISON, officially known as C/2012 S1, was announced on Sept. 24, 2012. Russian amateur astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok detected it in the dim constellation of Cancer (The Crab), through photographs taken days earlier using a 15.7-inch (0.4 meters) reflecting telescope of the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON), near Kislovodsk.

At that time, Comet ISON was estimated to be 625 million miles (1 billion kilometers) from Earth and 584 million miles (939 million km) from the sun.

January 2013: Space-based sightings

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA's comet-chasing Deep Impact probe — which has watched the flybys of icy wanderers like Tempel 1 and Hartley 2 — spotted ISON streaking across the night sky in mid-January.

Then, in late January, NASA's Swift Telescope turned its gaze toward ISON when the comet was 460 million miles (740 million km) away from the sun. The space agency unveiled the photo in March. The Swift data showed that ISON had not been shedding much water at that point — just 130 pounds (59 kilograms) each minute, compared to about 112,000 pounds (50,800 kg) per minute of dust, likely from evaporating carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide ice.

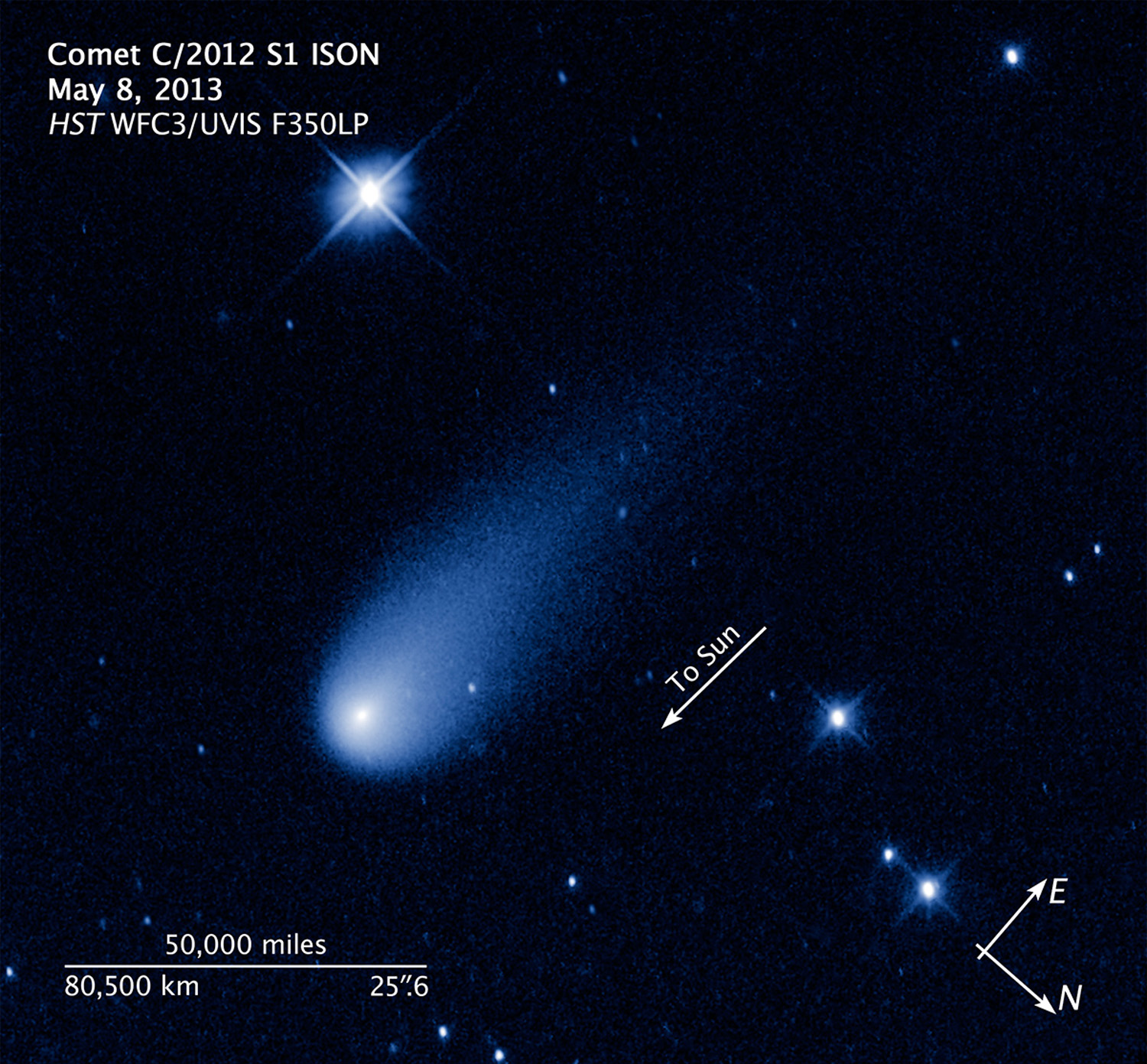

April 2013: Hubble sees ISON's small core

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope captured an image of ISON on April 10, 2013, when the comet was 386 million miles (621 million km) from the sun — slightly closer than Jupiter. Hubble data helped scientists see that the comet's nucleus is surprisingly small — no more than 3 or 4 miles (4.8 to 6.5 km) across.

Meanwhile, ISON's dusty head, or coma, is about 3,100 miles (5,000 km) wide, dragging a tail longer than 57,000 miles (92,000 km). Hubble also observed the comet in May and early July. [Comet ISON's Path Through The Inner Solar System (Video)]

June 2013: Spotted by Spitzer

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope observed ISON when the comet was 310 million miles (498 million km) away from the sun, but the data have not yet been released, space agency officials have said.

July-August 2013: Frost line crossing

Here's when things will start to get dicey for ISON. The comet is expected to pass the so-called frost line in late July or early August, according to NASA. At this boundary, some 230 to 280 million miles (370 to 450 million km) from the sun, the comet will be bombarded with enough radiation to make more of its water evaporate; ISON should then appear brighter. Some comets have not survived their frost line crossing.

Late August 2013: Back in view from Earth

Relative to Earth, ISON has appeared to be behind the sun since early June. By late August, astronomers will be able to see the comet through ground-based telescopes again. In September, the comet won't yet be visible to the naked eye, but skywatchers in the Southern Hemisphere should be able to see it near dawn with the aid of binoculars, according to NASA.

Sept. 17, 2013: Launch window opens for comet-watching balloon

A science balloon taller than the Washington Monument is set to launch from New Mexico to get a clear look at ISON, with minimal interference from the Earth's atmosphere. The Balloon Rapid Response for ISON (BRRISON) mission will soar almost 23 miles (37 km) above Earth, equipped with a 2.6-foot (0.8 m) telescope to observe the comet in infrared and near ultraviolet/visible wavelengths. Its launch window is Sept. 17 through Oct. 15.

Oct. 1, 2013: Mars flyby

NASA's Mars rovers Curiosity and Opportunity will have a view of ISON when it makes its closest approach to the Red Planet on Oct. 1.

Oct. 10, 2013: First STEREO-A sighting

One of NASA's two Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory probes, STEREO-A, will be able to see ISON through its HI 2 instrument when the comet is 94.5 million miles (152 million km) away from the sun.

Nov. 18, 2013: Launch window opens for FORTIS

A NASA sounding rocket dubbed FORTIS (Far-ultraviolet Off Rowland-Circle for Imaging and Spectroscopy) will measure ultraviolet light from ISON as the comet nears the sun, which can help scientists detect ISON's chemical makeup.

Nov. 19, 2013: Mercury flyby

Comet ISON will be visible to Messenger, a NASA probe orbiting Mercury.

Nov. 21, 2013: Telescopes turn to ISON

As ISON gets dangerously close to the sun, solar telescopes in space and on the ground will point their lenses toward the comet. NASA has a slew of STEREO observations planned starting on Nov. 21, including a series that will use tools called coronagraphs to block out the sun and focus on its atmosphere, or corona.

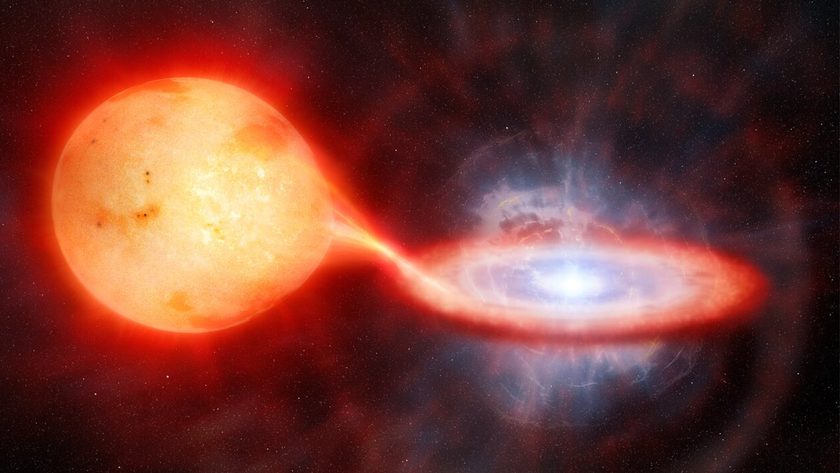

Ground-based solar telescopes will also capture images of ISON in optical, infrared and radio wavelengths. Scientists will be watching to see how the comet evolves as it makes its big approach. Intense solar radiation will cause material to evaporate quickly off ISON, and the pressure of solar particles could cause the comet to break up. An ill-timed solar eruption called a coronal mass ejection could even rip the comet's tail right off.

Nov. 28, 2013: ISON's perilous perihelion

Thanksgiving Day in the United States is ISON's big day. It will make its closest approach to the sun, or perihelion, skimming just 730,000 miles (1.2 million km) or so above the surface.

December 2013: Weeks-long show

If ISON survives its close solar pass, it could light up the sky in the Northern Hemisphere for weeks. The comet could be visible in the morning low on the horizon to the east-southeast in early December. Later in the month, and into early January, it could be visible all night, according to NASA.

Dec. 26, 2013: Closest pass to Earth

Before it heads back into the outer reaches of the solar system, the comet, or what's left of it, will make its closest approach to Earth, at roughly within 39.9 million miles (64.2 million km).

Editor's note: This article was corrected at 5:45 ET to reflect the correct distance of Comet ISON at its closest approach to Earth (approximately 39.9 million miles).

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.