Manned Mock Mars Mission Wrapping up in Hawaii

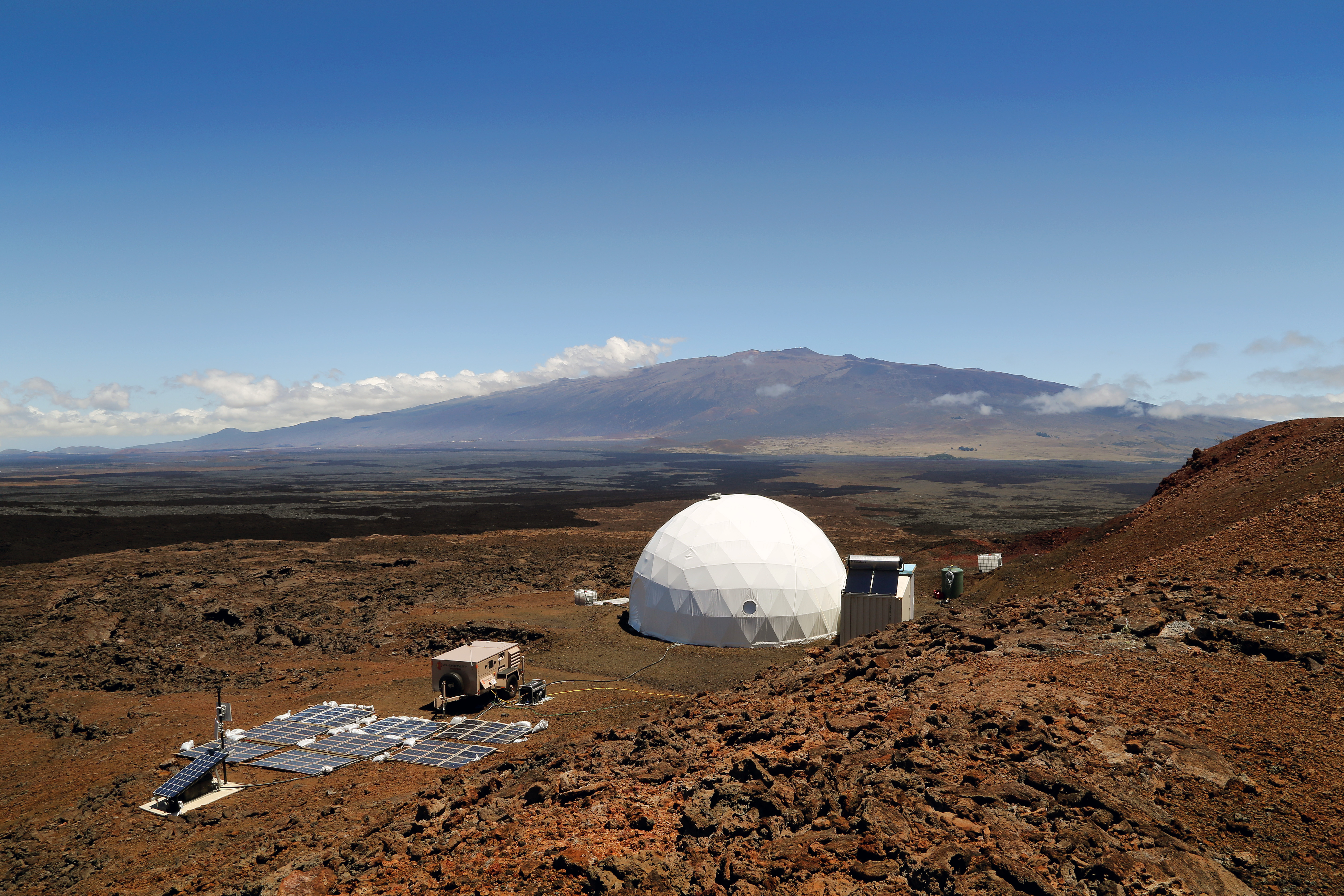

The Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) is nearing the end of its 120-day mission on the northern slope of Mauna Loa.

Since mid-April, six people have been living in a space habitat located 8,000 feet (2,440 meters) above sea level, on a barren lava field that is as Mars-like an environment as you can find on Earth. They've acted as though they were the first human explorers on Mars, not only conducting various science experiments and going out into the field dressed in simulated spacesuits, but also making meals with food that could survive the long voyage to the Red Planet.

HI-SEAS Commander Angelo Vermeulen spoke with Astrobiology Magazine editor Leslie Mullen via email about the mission as it approaches its end on Aug. 13. [Photos: 2013 HI-SEAS Mock Mars Mission]

You're now in the final stretch of your "time on Mars." How is the mission going so far?

The mission is rolling, and we're working hard to get as much done before it's all over. Days and weeks fly by at lightning speed. We're doing the main food study, but then there's also several personal research projects, opportunistic research for other research partners, EVAs, and a lot of surveys and logging. We definitely have not experienced the boredom or lethargy that has been popping up in other isolation studies!

I think time is actually our biggest enemy. We hardly ever finish a day where we completed what we had planned, and that obviously does generate a certain amount of stress. However, we got through the feared third quarter relatively unscathed.

Being a Commander adds a lot to one's life in these conditions. It's a great position that I totally love. And it also ties in with my former community building work. Of course we've had discussions, mostly about scheduling, and how free form or organized things should be. But these discussions were limited. We have a very compatible crew, and we like to talk. That makes things a lot easier. But the fatigue definitely shows. We could all use a week off to sleep in and recharge our batteries.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tell me more about the food study: What food has been the biggest hit? The most problematic to prepare? The least liked? If you could pick some of the food to take to Mars, what would make your list?

The pre-prepared favorites include: creamy wild rice soup, mashed potatoes, Tasty Bites with instant rice, raspberry crumble, apple sauce, and crackers. [Space Food Photos: What Astronauts Eat]

There's also been a lot of really good cooked dishes. Some of our crew members are accomplished cooks, and every week there are different surprises. Some success meals were Russian borscht, Moroccan tagine, enchilasagna, seafood chowder, and fabada asturiana. Wraps work really well: we combine tortillas, different vegetables, Velveeta cheese, and sausage or canned fish into ever-changing combinations. This is actually in line with the success of tortillas at the ISS. In general, the dehydrated and freeze-dried vegetables are a real success. They're used on a daily basis in almost every meal.

The freeze-dried meat is only really enjoyable when used in meals. In itself it's too bland and hardly has any aroma. Our least favorite pre-prepared meal must be 'Kung Fu Chicken.' This gets tiring really fast. Notwithstanding several ingredients, it has a rather flat taste, and the texture of the meal could be best described as 'slimy.'

The advantages of using pre-prepared meals is that they're less time consuming and less stressful. Hardly any thinking is needed. But of course, they're also less culinary satisfying. Usually more water is needed when cooking a meal from scratch due to the larger clean up.

One surprising finding is that we hardly drink sugared drinks. We started off with Tang and finished our supply in no time, but after that other sugared drinks were hardly touched. We mostly drink water, tea and coffee.

Ingredients that will be essential for future space missions on Mars or the moon will include spices, herbs and hot sauce. But also comfort food such as Nutella, peanut butter and margarine. And then enough ingredients rich in fiber. The problem with shelf-stable ingredients is that they're usually highly processed and hence lacking fiber. We enjoy wheat bread, rye crackers, nuts, and dried fruits, for example.

Have you experienced any "food fatigue" associated with eating packaged food for an extended period of time?

Not too much really. We actually have a large selection of ingredients to work with. Not so much because that's what astronauts on Mars will actually have at their disposition. We're here to experiment and figure out what works and doesn't work. Once that's more clear, the pantry will be reduced to more specific selection. As a consequence we still have quite some variation in our shelf-stable ingredients. And luckily we got really talented cooks on board. It's essentially some of the pre-prepared food that we quickly got tired of. That Kung Fu Chicken always comes back to mind.

Have the crew members lost weight, as often happens with astronauts on the ISS?

Four crew members (including myself) lost a bit of weight (5-8 lbs), and two crew members put themselves on a weight loss program. Unintentional weight loss might be caused by the different food, but definitely also by our daily workout routine. All of us exercise way more in the hab than in our regular life.

The workout program is part of a study for NASA to develop an advanced clothing system for exercise and sleepwear. The primary objective of the study is to estimate the length of time that exercise clothing and sleepwear can be used before it is found to be objectionable to the wearer. Differences in length of wear will be estimated as a function of fabric type and – more crucially – antimicrobial treatment.

Are you working on a personal research project, or is being the Commander taking up all of your time?

Two of my personal research projects are part of my current PhD research on evolvable space systems at Delft University of Technology. My research group, Participatory Systems, is looking at new design paradigms for socio-technical ecological systems. Space habitats are a good example of such systems where the social, technical and ecological intimately integrate. At HI-SEAS I look at how biological and social dynamics interact with the technological context and constraints of the mission.

I still have to properly analyze all quantitative data, but I already discerned some trends in my social research. Coping mechanisms seem to fall into three categories: (a) control, (b) creativity, and (c) projection. Strictly adhering to routine procedures and schedules, and purposely working with task lists are all methods to keep control over the workload during the mission. [Mars One's Red Planet Colony Project (Gallery)]

Painting, photography and writing are used by different crew members and provide a source of satisfaction and well-being. We received different 3D printers which are also used for creative expression. There's equally a lot of ways in which crew members project themselves outside of the confines of the habitat. Two crew members listen regularly to music from their youth bringing them to "a different place and time." Other crew members play computer games at the end of the day, and as such jump to a different virtual world.

For the biological component of my research I have been developing a remote-operated robotic farm, in collaboration with Simon Engler (HI-SEAS crew member) and Ileana Argyris (HI-SEAS mission support). The focus of this research project is to use robotic arms instead of conveyer belt-inspired plant-growing systems for space settlement.

The idea is that a human operator still makes basic decisions, but labor is subsequently carried out by the robot. Since at first no or little organic material (such as compost) will be available. Hydroponics is the initial technique to grow plants. During a later stage of space settlement a surplus of organic waste might become available and can be used to set up soil-based farming in association with hydroponics.

We are comparing two substrates for the hydroponics: local cinder from Mauna Loa, and commercial hydroponics substrate. The farm is set up in a different location on the Big Island of Hawai'i. Currently we have plants growing in the hydroponics system, and we can control the robot arm, the environmental sensor/control system, and webcams from within the HI-SEAS hab.

"Seeker" is my latest community art project. It's is a worldwide series of co-created spaceship sculptures that evolve over time. At its core, it's a community art project that invites people to fundamentally rethink the future of human habitation and survival. This is achieved by radically interconnecting technology, ecology and people, while at the same time tapping into local traditions. Fellow crew members Yajaira Sierra-Sastre and Kate Greene are actively collaborating with me to set up a HI-SEAS inspired version of Seeker in Puerto Rico after the mission (https://www.facebook.com/seekerproject).

Finally, I'm also working on a highly personal series of photos about my experience here. It has documentary value, but it is essentially a subjective interpretation of the mission. I'm hoping to create a publication and exhibition with this.

Tell me about an EVA: How long does it take to prepare for one, what sort of things do you do in the field, and then what is the procedure for returning to base? How often do you go on an EVA, and do you look forward to it because it frees you from the confinement of the habitat, or is it so much work that you lose the feeling of freedom you might expect to have?

An EVA can easily take up to an hour to prepare. Especially since we're testing different suit designs, and they all require individual procedures. Getting all the cooling systems, drinking packs and comms systems in place and properly working is what takes most time. Here's an excellent blog post from fellow crew member Kate Greene about our EVAs: http://www.economist.com/node/21576562

We go out at least once a week. The objectives are terrain exploration (including thermal imaging), geological identification (we have a field spectrometer at the hab), and microbiological detection. The microbiology research is a pilot study to investigate the presence of microorganism communities in lava fields by subsequent crews. It is carried out by science officer Yajaira Sierra-Sastre in collaboration with crew geologist Oleg Abramov. Myself and our outreach officer Sian Proctor also photo document the EVAs in detail. Apart from that, our crew engineer Simon Engler carries out daily EVAs to check life support systems. And Sian often goes out in the evening for night sky photography (all suited up).

EVAs are carefully planned, mostly by Oleg. We use GPS units to follow the designated route, while at the same time we stay in radio contact with HabCom. It is tremendously refreshing to go out on an EVA. Not necessarily in a literal way, because not all areas of the suits are equally well-cooled, but rather in a mental way. We only have one small porthole in the hab, so being outside surrounded by a vast landscape and open sky has a deep psychological impact.

How have you coped with the social pressure of being cooped up for a large stretch of time? You said your crew is compatible, but are there problems or issues that have arisen that you think its important for future missions to be concerned about? Have any romantic relationships formed over the course of your study? Being in close confinement while sharing an intense experience often leads to romance in mixed crews such as yours.

Most of the things that I assumed that would be difficult haven't been very difficult: the sheer physical isolation, the limited living space, living closely with 5 colleagues 24/7, reduced contact with friends, family and loved ones, potential boredom, etc. I definitely long to see my friends and family again, and I think about hiking, and swimming in the ocean, but it's not something I consider difficult.

What ended up being most difficult is managing time. Days and weeks seem to fly by at lightning speed. We all struggle with our schedules, which are filled with research activities, surveys, logging, meeting, cooking, and exercising. I don't think we ever finish a day where we completed our personal to-do list that we announced during the morning briefing. It can be frustrating at times, especially since we're all pretty ambitious people, and we want to churn out results and papers. We truly want to move human space exploration forward, and we want this mission to be as effective as possible.

On the upside, this intense pace is the perfect antidote against boredom and lethargy. A lot of press attention has been given to the Mars500 mission and the psychological problems that were observed. Elevated levels of boredom and lethargy were present throughout most of the mission, and it was only during the last 20 days that the crew got back into a high-productivity state.

I don't know enough about the specific conditions of Mars500 to pinpoint the exact origins of the difference with our mission. There's of course a big difference in duration. Four months is a period that is relatively easy to grasp. Getting somewhat bored during a 500-day isolation might be inevitable. But I also suspect that the high level of autonomy that the HI-SEAS principal investigators Kim Binsted and Jean Hunter granted us is partially responsible for our high productivity. This includes being able to define our personal research, something which is rather unusual in human space flight. Astronauts are typically 'operators' that carry out well-defined, predefined experiments. [Mars500: Photos From Russia's Mock Mars Mission]

Here at HI-SEAS we're pursuing very personal interests, give each other feedback, and help each other out on a daily basis. It's a great opportunity to be able to create during HI-SEAS, and not just blindly follow procedures. This is hugely motivational, and is one of the reasons we usually work long days. Now, less than two weeks away from the end of the mission, we're in a rush to make sure we can get everything done that we intended to.

In the context of my social research, I also set up a small experiment. I decided to offer my Commander role to the crew to allow everyone to broaden their experience, and get as much out of HI-SEAS as possible. I also learned from this by witnessing different styles and approaches. Four out of five other crew members were interested. Each week someone else took over the commander role for three consecutive days. After that we discussed the experience.

There's a few things that I value a lot in my personal leadership style, but through this particular experiment I learned there are many ways to lead. As a Commander I also learned that it's crucial to keep people talking, and keep the group (physically and emotionally) together. The worst that can happen is everyone working in their own little room all day long. I actively prevent that.

The design of the habitat is really well done (and was mainly the work of Paul Ponthieux of Envision Design). We live in a geodesic dome with one extra floor that covers half of the space. As a consequence, we have an open common space, and small – but comfortable – personal bedrooms on the second floor. The first month we lived without any windows at all. But then one small porthole got added and we can now enjoy sunset during dinner. As an artist I highly value well-balanced and aesthetic design, and this is definitely a good example of that.

It's not all work, though; we organize movie nights about twice a week during which we each present a favorite movie or documentary, and introduce it for the others. Recently we've started crafting short pre-shows: personal home videos or slide shows, favorite YouTube videos, game trailers, etc. And then there's Sundays. That's the moment where we stop our train of activities. We sleep in, and catch up with friends, family and loved ones, and work on personal stuff. This is highly needed to recharge our batteries to cope with the intense rhythm.

I'm afraid I have to disappoint you: no romance here. We all have partners, and we're in communications with them. Four months is not that long, so I think we'll handle it. Of course, if you would lock up six mixed singles for a year you could expect some romance, but don't underestimate the fact that it's quite sobering to live so close to each other. There are few secrets left, and you see each other in best but also worst moments. That's not always conducive for romance.

What's on the schedule for the time remaining? What is the procedure for "returning to Earth?"

Honestly, we're mostly trying to churn out as much data and results as we can. We all want to generate a nice stack of scientific papers after this mission.

On the 13th when we get out, we'll be greeted by international media. Not sure how that's gonna feel. We might just want to stare at the sky and the sun and the landscape, breathe fresh air, and not talk. My fellow crew members already suggested that I should do the talking since I'm the Commander. Not so sure if that's a good idea.

The first days after we get out we'll have a detailed debriefing with principal investigators Kim Binsted and Jean Hunter. There's several recommendations and ideas we want to bring up for the next HI-SEAS missions (which I cannot disclose right now). And we'll be having individual interviews and tests.

What do you plan to do when this adventure is over?

After all that I'm off to the TED Fellows Retreat in Whistler. A gathering of 300 fellows right after four months of isolation — that's bound to be interesting. I'll give a TED Talk on HI-SEAS there. I return to Hawaii after and will stay for a month, both for following up on HI-SEAS and taking time off.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leslie Mullen is an award-winning science photojournalist who has produced TV, radio, podcasts, live stage shows, and web features. Her work has been featured by NASA, PBS, National Geographic Channel, and other media outlets. Recently, Leslie has worked as writer, producer and host of the NASA/JPL podcast, "On a Mission," which was part of JPL's 2019 Emmy Award for "Outstanding Original Interactive Program." The podcast was awarded the gold medal for best technology podcast at the 2019 New York Festivals Radio Awards, and was a 2019 Webby Award honoree for best science and education podcast.